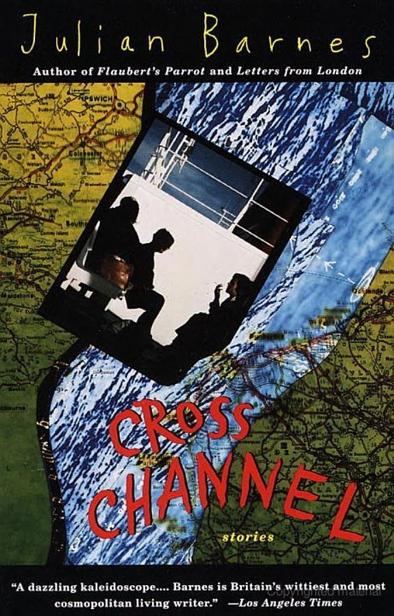

Cross Channel

Authors: Julian Barnes

Cross Channel

Julian Barnes

Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group (2010)

Tags: Fiction, Short Stories (Single Author)

Fictionttt Short Stories (Single Author)ttt

In his first collection of short stories, Barnes explores the narrow body of water containing the vast sea of prejudice and misapprehension which lies between England and France with acuity humor, and compassion. For whether Barnes's English characters come to France as conquerors or hostages, laborers, athletes, or aesthetes, what they discover, alongside rich food and barbarous sexual and religious practices, is their own ineradicable Englishness. The ten stories that make up Cross Channel introduce us to a plethora of intriguing, original, and sometimes ill-fated characters. Elegantly conceived and seductively written, Cross Channel is further evidence of Barnes's wizardry.From the Trade Paperback edition.

ACCLAIM FOR

Julian Barnes’s

C

ROSS

C

HANNEL

“Barnes has in abundance style and intelligence.”

—

The New York Times Book Review

“There appears to be nothing within the range of English prose that Julian Barnes cannot do…. Cross Channel [is] Barnes’s smart and funny collection of stories.”

—

Cleveland Plain Dealer

“These are learned stories, each written in the style of its age or its characters. Some carry echoes of Somerset Maugham or Guy de Maupassant. Some are pure originals.”

—

Washington Post

“Finely balanced stories…. Artful narratives linked together by the shadows and crosscurrents between England and France…. Barnes has exposed both biases and fallen prey to neither.”

—

Boston Globe

“Barnes keeps us pleasurably off-balance. We read these stories as we might ride a horse that is a little more than we can manage; we become riders who surprise ourselves.”

—

Newsday

“The opening of the English Channel tunnel marks the end of the old relationship between the English and the French. Barnes’s creative synthesis in this collection catches that moment hauntingly, while providing very fine reading pleasure.”

—

Washington Times

Julian Barnes

C

ROSS

C

HANNEL

Julian Barnes was born in Leicester, England, in 1946, was educated at Oxford, and now lives in London. He is the author of seven novels—including

Flaubert’s Parrot, A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters

, and, most recently,

The Porcupine

—and a book of essays,

Letters from London

.

BOOKS BY

J

ULIAN

B

ARNES

Metroland

Before She Met Me

Flaubert’s Parrot

Staring at the Sun

A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters

Talking It Over

The Porcupine

Letters from London 1990-1995

Cross Channel

TO PAT

CONTENTS

I

NTERFERENCE

H

E LONGED FOR DEATH

, and he longed for his gramophone records to arrive. The rest of life’s business was complete. His work was done; in years to come it would either be forgotten or praised, depending upon whether mankind became more, or less, stupid. His business with Adeline was done, too: most of what she offered him now was foolishness and sentimentality. Women, he had concluded, were at base conventional: even the free-spirited were eventually brought down. Hence that repellent scene the other week. As if one could want to be manacled at this stage, when all that was left was a final, lonely soaring.

He looked around his room. The EMG stood in the corner, a monstrous varnished lily. The wireless had been placed on the washstand, from which the jug and bowl had been removed: he no longer rose to rinse his wasted body. A low basketwork chair, in which Adeline would sit for far too long, imagining that if she enthused enough about the pettinesses of life he might discover a belated appetite for them. A wicker table, on which sat his spectacles, his medicines, Nietzsche, and the latest Edgar Wallace. A writer with the profligacy of some minor Italian composer. ‘The lunch-time Wallace has arrived,’ Adeline would announce, tirelessly repeating the joke he had told her in the first place. The

Customs House at Calais appeared to have no difficulty allowing the lunch-time Wallace through. But not his ‘Four English Seasons’. They wanted proof that the records were not being imported for commercial purposes. Absurd! He would have sent Adeline to Calais had she not been needed here.

His window opened to the north. He thought of the village nowadays solely in terms of nuisance. The butcher lady with her motor. The farms that pumped their feed every hour of the day. The baker with his motor. The American house with its infernal new bathroom. He briefly thought his way beyond the village, across the Marne, up to Compiègne, Amiens, Calais, London. He had not returned for three decades — perhaps it was almost four — and his bones would not do so on his behalf. He had given instructions. Adeline would obey.

He wondered what Boult was like. ‘Your young champion’, as Adeline always characterised him. Forgetting the intentional irony when he had first bestowed this soubriquet on the conductor. You must expect nothing from those who denigrate you, and less from those who support you. This had always been his motto. He had sent Boult his instructions, too. Whether the fellow would understand the first principles of Kinetic Impressionism remained to be seen. Those damn gentlemen of the Customs House were perhaps listening to the results even now. He had written to Calais explaining the situation. He had telegraphed the recording company asking if a new set could not be dispatched contraband. He had telegraphed Boult, asking him to use his influence so that he might hear his suite before he died. Adeline had not liked his wording of that message; but then Adeline did not like much nowadays.

She had become a vexing woman. When they had first

been companions, in Berlin, then in Montparnasse, she had believed in his work, and believed in his principles of life. Later she had become possessive, jealous, critical. As if the abandoning of her own career had made her more expert in his. She had developed a little repertoire of nods and pouts which countermanded her actual words. When he had described the plan and purpose of the ‘Four English Seasons’ to her, she had responded, as she all too regularly did, ‘I am sure, Leonard, it will be very fine’, but her neck was tight as she said it, and she peered at her darning with unnecessary force. Why not say what you think, woman? She was becoming secretive and devious. For instance, he pretty much suspected that she had taken to her knees these last years.

Punaise de sacristie

, he had challenged. She hadn’t liked that. She had liked it less when he had guessed another of her little games. ‘I will see no priest,’ he had told her. ‘Or, rather, if I so much as smell one I shall attack him with the fire-tongs.’ She hadn’t liked that, oh no. ‘We are both old people now, Leonard,’ she had mumbled.

‘Agreed. And if I fail to attack him with the fire-tongs, consider me senile.’

He banged on the boards and the maid, whatever was her name, came up at a trot. ‘Numéro six,’ he said. She knew not to reply, but nodded, wound the EMG, put on the first movement of the Viola Sonata, and watched the needle’s stationary progress until it was time, with fleet and practised wrists, to flip the record over. She was good, this one: just a brief halt at a level crossing, then the music resumed. He was pleased. Tertis knew his business. Yes, he thought, as she lifted the needle, they cannot gainsay that. ‘Merci,’ he murmured, dismissing the girl.