Crossing the Borders of Time (58 page)

Alice closed with a pointed observation:

I am happy your son came home safely from the war. I felt scared for him. At his age, with his enthusiasm and his zest for the Thing, he was surely in the front rows of the battle and an eager Wehrmacht soldier. It must have been hard for you. It must have not been easy for you either, dear Herr Nagel, to repeatedly change your lifestyle and your livelihood. How much misery there is in this context among the refugees you cannot begin to guess. All those people lacking money and knowledge of the [English] language have no choice but to accept the most unbelievably lowly jobs. This is a misfortune of our times that has spared no one, but rather it has hit all mankind.

The change of “lifestyle and livelihood” that Alice so empathetically mentioned in her letter in regard to Herr Nagel was something she understood firsthand. In coming to New York, she had found her sister Rosie living in a dismal railroad flat in a walk-up building in the South Bronx, renting out a room to a boarder. Rosie’s husband, Natan Marx, once the proud proprietor of the family business in Eppingen, was earning $40 a month washing dishes and pots in a sweltering hospital kitchen in Brooklyn. (A heart attack would kill him in 1949 at the age of sixty-two.) Their daughter Hannchen, sixteen years old when they immigrated at the end of 1938, had been helping to support her parents by working for $28 a month as a live-in maid in the Bronx.

Spared such hardships that other refugees encountered, Sigmar and Alice lived lives of small routine. On days that Sigmar did not go down to Wall Street trailing Max, his business activities consisted of devouring the financial pages of

The New York Times

in the mornings and

The Herald Tribune

in the afternoons, which provided little more in terms of social engagement than a regular impetus to walk to the newstand. Several times a week, he met with Max to play their favorite German card game. On very rare occasions, he and Alice splurged on tickets to the Metropolitan Opera—especially for Wagner—or to Carnegie Hall for a master pianist playing Chopin or Beethoven. But their experience in America was generally confined to Inwood, where they were content with the close proximity of family and other German Jewish refugees who shared their simple gratefulness to be alive.

With his grandchildren in the building, Sigmar mellowed, and the stern authoritarian that Janine, Trudi, and Norbert remembered fearing in their youth was replaced by a kind and doting patriarch—“Bapa,” adored by all. He taught me how to read from the pages of his newspapers, inspiring my interest in journalism. And he never missed an opportunity to lead me, humming, in stately bridal march down the length of his apartment, culminating in a solemn ceremony in which he placed the golden paper band from his cigar like a wedding ring upon my finger.

Almost as soon as Alice and Sigmar moved into the building, their next-door neighbor, a schoolteacher named Lou, started to give them English lessons. For homework, Lou had them fill lined composition books with page after page of random statements and spontaneous thoughts that roamed disjointedly between the political and personal. Sigmar in ink and Alice in pencil, they diligently practiced writing in English and wound up creating haphazard journals as both voiced feelings they normally stifled.

From Sigmar:

Everybody has his deal of misfortune. It is better to live in the present than always to remember times past. Many refugees arrive without a single dollar in their pockets. The moment I could leave Europe I was a very happy man. Great nations should work for peace but keep the sword always sharpened for their defense. History will judge our generation as foolish, making wars one after another and destroying millions of people and the prosperity of the countries. Going to the stock market is a hazard. I should like to give all war criminals to the judgments of the Russians. A ruined Europe is all what the war left.

And Alice:

A person who travels from one country to another for religious reasons is called a Pilgrim. The Jews are not welcome in any country. To speak a foreign language is hard for older people. Mistakes are human. Life is hard especially in our time. It is very helpful to have a good dictionary. There will be joy and laughter and peace when the world is free. I wish I were able to support the poor. I spend most of my time in the kitchen. It is a long time since I left my home. Old furniture is better than new furniture. I owe my home and my freedom to this country. I will never return to Europe.

As it happened, despite her resolve, Alice would travel there twice, overcome by longing to visit her brother in London. On her first solo trip, in 1957, en route to see family in Zurich as well, she stopped in Freiburg, gravitated to the Poststrasse, and checked herself in to the Hotel Minerva. It was now being run by the Schöpperles’ daughter, Rosemarie, and her husband, Friedrich Stock. While they were polite, it was upsetting for Alice to see how the ivy-draped premises of the Minerva had swallowed her home—the place where all three of her children were born and where she’d enjoyed the properous early years of her marriage.

Across the street on the Rosastrasse stood Sigmar’s former business, now called Eisen Glatt. That afternoon, Alice went to gaze in silence at the department store once owned by Trudi’s husband’s family. “Nebbish!” she wrote home, summarizing sad emotions of disbelief on the back of a postcard that showed the Minerva. She mailed it before she climbed the stairs and went to bed that night, but hours later, unable to fall asleep in Germany as a paying guest in what should have been her own home, she packed her things and called a taxi to take her across the border to Mulhouse. Never again would Alice go back to Germany. Or France.

When she reached Mulhouse late that night, she went directly to the Hotel du Parc, among the city’s finest, and asked in English for a room. But in the empty lobby at that hour, Alice overheard the hotel clerks make fun of her: “

Quelle idiote! Avec cet accent alsacien, elle ne parle aucun mot de français?

” What an idiot! With that Alsatian accent, she doesn’t speak a word of French?

“No, not an idiot,” Alice retorted in French with the bravado of her girlhood as

die freche Lisel

. “Just an American.”

In the land of my early childhood, no disrespect to Alice, it was my father who stood apart as the sole American. He was the man to count on for directions and information and who drummed up conversation to keep Sigmar entertained. He worked to master French and German, learning lengthy lists of foreign words and complex rules of German grammar to translate for his in-laws, editing their correspondence for proper English usage. In language and self-confidence, know-how and personality, he had no equal. On Sundays, when he played tennis near the Harlem River with Trudi’s husband, Harry, he competed in raiment I took to be symbolic—a classic tennis sweater that Alice knitted for him with thick white cables and stripes of red and blue around the sleeves and V-neck. It seemed a costume meant for him alone, an entitlement of birth and nationality, especially as my uncle never had a sweater like it, with its bold tricolor citizen’s assertiveness. My American father wore that sweater like the flag, and I was proud to be his daughter.

It was rare, however, that my mother or my brother and I got to spend much time with him. Mom had given up her job when I was born, and we spent long summers in a rustic rental on a lake, where Dad could get away to join us only on weekends. But our familial city life was replicated in the country also, for Trudi and Harry and Norbert and Doris also rented lakeside houses just steps away from ours. On Friday nights, the men drove up with string-tied ziggurats of Nash’s baked goods and a week’s supply of dirty laundry for their wives to wash and iron, and they returned to the city early Monday mornings.

For the rest, Len was often driving out of town on business trips that continued to leave him lonely and disconsolate and determined to reach beyond his salesman’s route and salary. When he was home, he repeatedly debated with Janine the wisdom of striking out in business for himself—a conversation complicated by his being optimistically impetuous, while she was highly risk averse and all too well acquainted with the randomness of danger. Based on agreements with two industrial manufacturers to represent their products in East Coast regions, he quit his job, founded his own company, calling it Unisco, and rented office space not far from the apartment. Energized and instinctively a boss, he grew in stature and authority as he began to hire employees, even as they bristled under his perfectionism. Still required to travel, he lamented in letters from the road how hard it was to build sufficient sales to raise the level of his commissions from 2 percent to 5 percent, and so he logged even longer hours, working nights and weekends.

Though I seldom got to be with him, I loved him wholeheartedly and wanted nothing more than his attention and approval. For his part, he was driven to make me fearless and competitive, a process he regrettably began by pitting me in rivalry with my cousin Lynne, my alter ego and the friend with whom I spent almost every waking moment. Together we walked to P.S. 98 on 211th Street and back each day, traversing subway tunnels rather than crossing over Broadway, with its crush of traffic that our mothers thought more dangerous than the underground passageways of the Independent line. Often we were even dressed alike, in Madison Avenue finery passed down from Herbert’s daughters. Without exception, I always got the blue dress and my brown-eyed cousin the identical in pink, our mothers continuing the eye-color-based assignment that Alice had employed in outfitting her girls like twins many years before us.

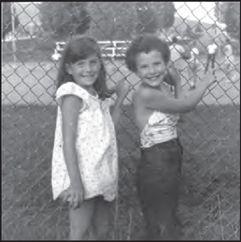

Leslie (L) and Lynne, cousins and constant playmates

Despite our closeness, my father contrived to set up constant contests, the first of which was based on height. Almost weekly, he placed us back-to-back to judge which one was taller, and I stretched as high and straight as possible, hoping to measure up for him. With his hand weighing on my head, I strained to roll my eyes behind me to check the outcome, but Daddy’s disappointment was invariably palpable, impelling me to offer him consoling explanations as we rode the three flights home from Lynne’s apartment together in the elevator.

“Lynne’s three weeks older!” I offered hopefully. “Are you sure you pressed her hair down?” All explanations he waved away, complaining that I would

never

grow to match her height unless I started eating more.

Determined as he was to make me strong and self-reliant, he was frustrated to have to battle a range of childish fears that were no doubt fanned by the apprehensive worries of our Nana and our mothers. For them, the experience of war and persecution seemed to leave a residue that clouded every day with the possibility of ending in disaster. My father, however, had no patience for limitations he regarded as irrational: he could not abide my fear of dogs, and when we went to an amusement park, it exasperated him to see me shrink away from any ride more dizzying than the Ferris wheel. My delight in spending precious time alone with him was inevitably tempered by anxiety that lacking nerve, I’d let him down.