Crows (4 page)

Authors: Candace Savage

But if Raven was opportunistic and often thoughtless, he was not malicious. He did the best he could for his new creations. Through trickery, theft, and seduction, he provided his people with everything they needed for survival: daylight, fire, rivers full of salmon and eulachon—even the knowledge of how to make love. The lusty Raven was only too happy to provide a demonstration. His spirit was so much like a person’s that he could transform himself into a human whenever he wished and pass himself off as a baby or a member of the opposite sex, usually with dire and twisted consequences. When Raven was on the scene, loved ones died under questionable circumstances, and precious possessions disappeared. And if his misdeeds were often wryly hilarious, his frailties were also unsparingly recognizable. But perhaps it is not surprising that the Raven and his people had so much in common, since each had created the other in his own image.

REVOLUTIONS IN EVOLUTIONSeen with the transforming eye of the imagination, the crows and ravens of mythology resemble people in fancy dress, a noisy and good-naturedly venal tribe of avian superheroes. But what happens when we consider the genus

Corvus

with the cold, hard gaze of science? Is there any factual basis for positing a special kinship between crows and humans?

Corvus

with the cold, hard gaze of science? Is there any factual basis for positing a special kinship between crows and humans?

At first glance, the evolutionary evidence does not looking promising. According to the paleontologists, birds and mammals are the products of two distinctly different branches of the tree of life. Their most recent common ancestor was a vaguely amphibianlike creature that lived in the swampy tropical forests of the late Carboniferous Period, at least 280 million years ago. At that point, the most advanced life-forms on the planet were aquatic or semi-aquatic organisms, such as fish and frogs, that were obliged to spend all or part of their lives in water. The progenitors of birds and mammals, by contrast, produced eggs with hard, mineralized shells that could be laid right out on dry land and thus marked an early, tentative step in the conquest of terra firma.

From that imponderably distant starting point, evolution followed two divergent paths. One lineage—known as the Synapsida, or “beast faces”—eventually gave rise to the earliest mammals, furry, scurrying, shrewlike creatures that appeared on the scene about 220 million years ago, during the late Triassic Period. Meanwhile, the other line—the Sauropsida, or “lizard faces”—evolved into all manner of reptiles, notably, the dinosaurs. Birds either descended from some anonymous reptilian ancestor and evolved alongside the mighty dinos (as witness a fragmentary but seductively birdlike fossil from Texas called

Protoavis,

which dates to about 225 million years ago) or else, as most experts contend, are descendants of the great beasts themselves (as witness the delicate fossil remains of feathered dinosaurs, dating back some

150 million years, that were recently discovered in China).

Protoavis,

which dates to about 225 million years ago) or else, as most experts contend, are descendants of the great beasts themselves (as witness the delicate fossil remains of feathered dinosaurs, dating back some

150 million years, that were recently discovered in China).

No matter how this question is eventually answered, one fact is clear: the evolutionary gulf between birds and mammals is almost incomprehensible. This conclusion comes as a surprise to those of us who grew up on biology textbooks in which the members of the classes Aves and Mammalia were typically presented together as warm, fuzzy creatures that, despite their differences, were each other’s closest living relatives. But with insights gained from an ever-improving fossil record and advances in genetic analysis, taxonomists have recently begun to emphasize not the kinship between the two groups but their disjunction. As the only surviving members of the synapsid lineage, mammals are placed in a class by themselves, but birds are now listed as a subgrouping of the reptiles: the class Aves in the clade, or evolutionary line, of Reptilia. And if it is true that birds—crows among them—are just glorified lizards, then what is the chance we could have anything significant in common with them? Perhaps the connection that we sense with crows and ravens is nothing but wishful thinking, an expression of our own deep yearning for intelligent company.

➣

Birds are thought to be the direct descendants of flying, feathered reptiles.

Birds are thought to be the direct descendants of flying, feathered reptiles.

But remember that life, like the mythic Raven, has a few tricks up its sleeve and is not to be stymied by mere improbabilities. Just as evolution can

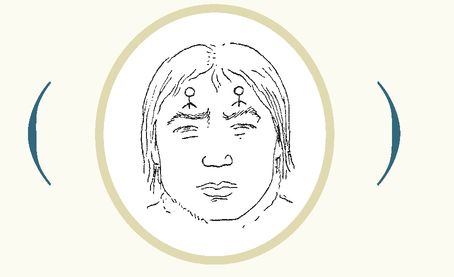

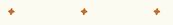

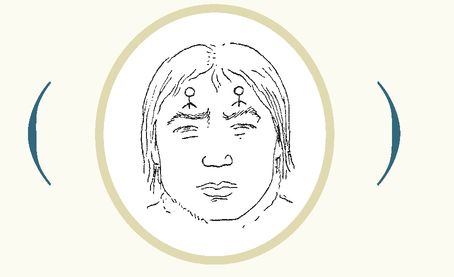

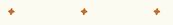

The face of a Yup’ik boy, with raven tattoos, 1890s.

The face of a Yup’ik boy, with raven tattoos, 1890s.

start with a single ancestral life-form and take it in different directions to produce wildly different results, so too can those divergent end points gradually converge, or begin to resemble one another. The power of flight, for example, has arisen at least three times from three evolutionary beginnings, in insects, reptiles, and mammals. Bees, birds, and bats are all airborne today because, through eons of time, their assorted ancestors responded independently to the opportunities and challenges of taking to the sky. Life is infinitely transmutable, and it is entirely normal and unexceptional for organisms from widely separated branches of the evolutionary tree to bend together and acquire similar characteristics. Does this kind of evolutionary convergence account for the connection between crows and humans? If it does, how alike have we two become? And why would anything so unlikely ever have happened?

CROW UNIVERSITY

The face of a Yup’ik boy, with raven tattoos, 1890s.

The face of a Yup’ik boy, with raven tattoos, 1890s.RAVEN MAKES THE FIRST PERSON

ABRIDGED FROM

THE WORDS OF AN UNALIT, OR YUP’IK,

STORYTELLER IN COASTAL ALASKA, AS RECORDED IN THE 1890S

THE WORDS OF AN UNALIT, OR YUP’IK,

STORYTELLER IN COASTAL ALASKA, AS RECORDED IN THE 1890S

I

t was in the time [the elders said] when there were no people on the earth. During four days the first man lay coiled up in the pod of a beach-pea

(L. maritimus.)

On the fifth day, he stretched out his feet and burst the pod, falling to the ground, where he stood up, a full-grown man. He looked about him,… and he saw approaching, with a waving motion, a dark object which came on until just in front of him.... This was a raven, and, as soon as it stopped, it raised one of its wings, pushed up its beak, like a mask, to the top of its head and changed at once into a man....

t was in the time [the elders said] when there were no people on the earth. During four days the first man lay coiled up in the pod of a beach-pea

(L. maritimus.)

On the fifth day, he stretched out his feet and burst the pod, falling to the ground, where he stood up, a full-grown man. He looked about him,… and he saw approaching, with a waving motion, a dark object which came on until just in front of him.... This was a raven, and, as soon as it stopped, it raised one of its wings, pushed up its beak, like a mask, to the top of its head and changed at once into a man....

At last he said: “What are you? Whence did you come? I have never seen anything like you.”

To this Man replied: “I came from the pea-pod.” And he pointed to the plant from which he came.

“Ah!” exclaimed Raven, “I made that vine, but did not know that anything like you would ever come from it.”

The ability to make and use tools has long been considered a hallmark of intelligence and one of the distinctive characteristics of human beings. (“The first indications that our ancestors were in any respect unusual among animals,” writes physiologist Jared M. Diamond in his book

The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee,

“were our extremely crude stone tools that began to appear in Africa by around two-and-a-half million years ago.”) And it is certainly true that tool use is a rare and remarkable achievement in the living world. For

example, of the roughly 8,600 species of living birds, only about 100 have ever been known to drop a shell on a sidewalk, batter prey against a wall, or do anything else that could even remotely be considered technological. If the scope of the discussion is narrowed to include only “true tool use”—the manipulation of objects that are held in foot or beak and used to accomplish a task—the number of species that qualify drops by more than half. By this definition, the list includes only such

rara avis

as the Egyptian vulture, which occasionally uses stones to hammer ostrich eggs, and various species of chickadees and tits, which sometimes use twigs to probe into crevices.

The Rise and Fall of the Third Chimpanzee,

“were our extremely crude stone tools that began to appear in Africa by around two-and-a-half million years ago.”) And it is certainly true that tool use is a rare and remarkable achievement in the living world. For

example, of the roughly 8,600 species of living birds, only about 100 have ever been known to drop a shell on a sidewalk, batter prey against a wall, or do anything else that could even remotely be considered technological. If the scope of the discussion is narrowed to include only “true tool use”—the manipulation of objects that are held in foot or beak and used to accomplish a task—the number of species that qualify drops by more than half. By this definition, the list includes only such

rara avis

as the Egyptian vulture, which occasionally uses stones to hammer ostrich eggs, and various species of chickadees and tits, which sometimes use twigs to probe into crevices.

The only name to show up time and again on the list of tool-using birds is

Corvus.

For example, there is a report from Oklahoma of an American crow that tore a sliver of wood off a fencepost, placed it under its feet, and pecked at the tapered end as if to shape the point. The bird then used its tool to poke into a narrow hole where a spider was hiding. In Scandinavia, carrion crows have been known to tug up ice-fishing lines, holding the tangled line with their feet between pulls and then flying away with whatever they can steal from the hook. And in the city of Sendai, Japan, members of this same species have learned to use cars as nutcrackers. The crows perch at controlled intersections, and when the cars stop on red, the birds swoop down and place the hard-shelled nuts in the path of the traffic. After the cars have moved through, the birds fly down to feed or, if the nuts are still intact, to reposition them for another try.

Corvus.

For example, there is a report from Oklahoma of an American crow that tore a sliver of wood off a fencepost, placed it under its feet, and pecked at the tapered end as if to shape the point. The bird then used its tool to poke into a narrow hole where a spider was hiding. In Scandinavia, carrion crows have been known to tug up ice-fishing lines, holding the tangled line with their feet between pulls and then flying away with whatever they can steal from the hook. And in the city of Sendai, Japan, members of this same species have learned to use cars as nutcrackers. The crows perch at controlled intersections, and when the cars stop on red, the birds swoop down and place the hard-shelled nuts in the path of the traffic. After the cars have moved through, the birds fly down to feed or, if the nuts are still intact, to reposition them for another try.

FOR THEIR SIZE,

{

CROWS

}

CROWS

}

areamongthe BRAINIEST organisms

on Earth,

outclassing

not only other

BIRDS

(with the possible exception of parrots)

but also most MAMMALS.

on Earth,

outclassing

not only other

BIRDS

(with the possible exception of parrots)

but also most MAMMALS.

Other books

Hare Today, Dead Tomorrow by Cynthia Baxter

Neither Wolf nor Dog by Kent Nerburn

TOUCH ME SOFTLY by Darling, Stacey

Dawn (When They Return Book 1) by Allen, M'Renee

A Date With the Other Side by Erin McCarthy

One Night of Surrender: The Brothers Mortmain, Book 1 by Evie North

Smiley's People by John le Carre

Camp Jameson by Wendy Lea Thomas

Dante by Bethany-Kris

Need for Speed by Brian Kelleher