Crows & Cards (2 page)

Authors: Joseph Helgerson

That pretty much did it—sealed my fate, so to speak. Pa smoldered for most of a minute, looking like he was about to blow cinders out his top any second. Finally he did, speaking up loud enough for our neighbors a half-mile distant to catch what was on his mind.

"Here's what's happening: You've got a great-uncle, name of Seth, who's down in St. Louis. He used to be a trapper on the Missouri but has turned to tanning in his dotage. Fact is, I hear tell he's the best tanner there is west of the Mississippi. When it comes to treating furs, he knows himself some secrets. Picked 'em up from the Indians, I shouldn't be surprised. We're going to put you on a steamer with a letter of introduction and see if he'll take you on."

Hearing that left me feeling buried alive, with Pa's every word landing like another shovelful of dirt atop me. When it comes right down to it, twelve-year-olds don't have much bargaining power, not with the likes of my pa. So it looked as if I was doomed to learn a trade that didn't have any future at all. What with beaver hats going out of fashion, the fur business was keeling over as we spoke. Beavers themselves were getting trapped out, as was pretty much every other living thing with the misfortune to wear fur and have four legs. Most all the river men said it. What's more, it wasn't just horsehair that made me sneeze—most any kind of fur would do. But when I tried to point out that working with hides might rip my nose apart, Pa claimed that us Crabtrees were made of sterner stuff than I knew. And on top of that, getting from Stavely's Landing to St. Louis would require riding one hundred and sixty-odd miles down the Mississippi on a steamer, which meant I could fall overboard and drown any second. I imagined I'd be turning a hundred and sixty-plus shades of green by the time I got there,

if

I got there. The only good thing about the whole undertaking was a chance to see St. Louis. The bad part of that was this: if St. Louis was only half as amazing as everyone claimed, I'd still probably be knocked blind by the sights.

CHAPTER TWO

T

HOUGH THAT CONVERSATION SNOWED DOWN ON ME

in midwinter, Pa and Ma couldn't ship me straight off to St. Louis on account of spring planting. It wasn't shaping up to be anywhere near a long enough spring planting from my view.

"You're a goner," Matilda told me. She was my oldest sister, born one year after me, and could generally get away with such spouting 'cause of her size.

"Not yet, I ain't."

"Heard Ma and Pa talking," she breezed on. "They're agreed. It's for your own good."

That news struck me like a blow 'cause I'd been angling to enlist Ma on my side, but if it'd already reached the for-your-own-good stage, then all was lost.

Everything fell to pieces on me after that. I couldn't seem to talk to no one without provoking some testiness, and scratch as I might, I couldn't uncover so much as a glimmer of hope anywhere. I tried everything, even taking an oath—one hand on the Good Book—that what I really wanted to do was stay home and help run the wood yard, slivers and all.

Didn't wash.

No amount of sass, cow-eyed sulks, filibustering, or flat-out refusals got me anything but trips to the smokehouse. Now some families maybe use their smokehouses for whippings, but being alone with yourself was how ours got put to use. Dark and gloomy as my thoughts were ranging, I almost wished Pa believed in using the strap for misbehaving. But no, I had to sit out there in the dark, with no one to talk to but myself and an old crow who used to come peek at me through a knothole. By the start of April I'd spent so much time out there that whatever that bird was croaking about came so close to making sense that I had to plug my ears. The only good that came of all that was my swallowing hard enough to tolerate fate: I was St. Louis bound.

Pa had even written my Great-Uncle Seth, wanting to make sure he was still alive and would have me.

Yes and yes—for a fee.

Having to cough up money for this apprenticeship of mine nearly saved the day. Pa grumbled about the old skinflint and slammed logs around the wood yard for most of a week before hunkering down and making up his mind: if they was ever going to get rid of me, they'd have to sell off some livestock. In the end he had to unload half our cows and a fine old sow to scrape up seventy dollars, which would buy me six years' training. If I worked out, I'd start earning a dollar a week after three years. That would get bumped up to two dollars after five years. Out of these wages I'd have to buy my own clothes, pay for any doctoring I needed, and set aside enough to repay seventy dollars to Ma and Pa, leaving them fee money for my younger brothers. Food came with the job, though I'd probably have to cook it myself.

Leastways, that's how my contract read. Me, I was wondering what kind of great-uncle charged his own flesh and blood seventy dollars for a chance to work with a bunch of smelly old hides.

***

Come mid-April the corn and oats was in the ground, and my folks were driving me down to Stavely's Landing on the buckboard. Pa bought me a ticket for the

Rose Melinda,

a big side-wheeler hauling lead from the mines at Galena and picking up passengers on the way downriver. Once to the levee, he tucked the letter of introduction, along with the seventy-dollar fee and directions to my Great-Uncle Seth's place, inside my pants for safekeeping.

"Seth will work you hard but probably not to death," Pa said, giving my hand a shake. "Good luck, son."

My ma gave me a hug along with some advice. "Remember your reputation. It's worth more than gold."

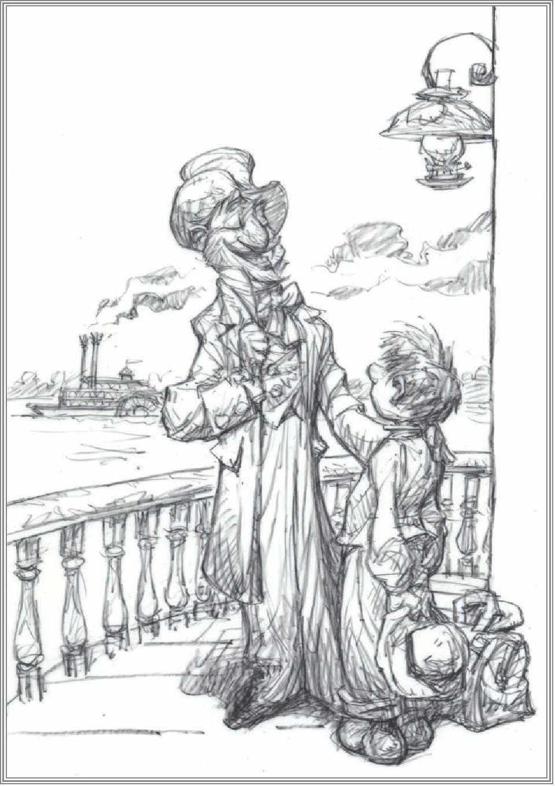

Then she rustled away before coming up a hankie short. Back at the wagon, my brothers, James, Harold, and Lester, were watching mighty close. My sisters, Matilda, Rebecca, and Emily, weren't missing anything either. Up to that very moment, there'd always been seven of us kids who showed up at the dinner table, and that had seemed like the way it'd always be. The only world we'd ever known was our log cabin, which stacked up as a pretty special place, living along the Mississippi as we did. There wasn't nothing but dark woods and tall bluffs all around us, and at night the lights from Quincy, across the river in Illinois, twinkled away like jewels in a crown. The days, they stretched out forever before us, or so we had believed. Given the curious and shocked way my brothers and sisters were watching my departure, other possibilities were dawning on them. Every step I took left me feeling as though I was about to stumble over the edge of a cliff and the whole world seemed to be holding its breath to see how far I'd fall. Hang it all, there was even a dab of wet smearing up my eyes.

But none of that stopped Pa from walking me up the boarding plank and putting my ticket for deck passage in the purser's hand. The ticket cost him two dollar and ten cents above and beyond the seventy-dollar apprentice fee. That done, Pa removed himself from the ship, leaving me all alone for the first time in my life.

Of course, strictly speaking, I wasn't anywhere near alone, not with all the strangers crammed on that steamer, but just then I wasn't paying them any mind. I was too busy watching Pa. He stood on shore while the

Rose Melinda

rang her bells and blew her whistle and backed out into the river. It took only a minute or two, but as minutes go, they were about as jam-packed as any I'd ever find. There were more things swishing around inside me than I could count, and outside of me, deck hands were rushing everywhere with cargo and shouts.

From the wagon, Ma and the others made little, tiny hand waves goodbye, as if their arms were broke. Pa didn't even manage that much.

He stood alone, still as a fence post till he was nothing but a speck on the shore behind us. Then I couldn't see him at all, though I kept looking. Something beneath my ribs told me he hadn't budged yet. What with all them mouths to feed, I'd never seen Pa stand in one place for more than a few seconds, but somehow I knew he'd stay standing on that levee, just to make sure I didn't figure out some way off the boat. My escaping was an unlikely proposition, surrounded as I was by all that water, and I suppose it was awful smallish of me to think that's why Pa stood there watching. Hadn't he been the one to fetch the doc for me in that ice storm? And hadn't he, who swam about as good as a heavy rock, somehow saved me from drowning that time I was fooling around and fell off the ferry? And weren't there a thousand or more other

hadn'ts

to boot, every one of them adding to the bulge in my throat? No, something deep inside me said he'd stay planted on that shore till my steamer was long gone and Ma came to get him. But he wouldn't be standing there 'cause he didn't trust me. There were deeper wells than that to the man, or so I told myself.

At the same time, I couldn't help but wonder what kind of folks did such a thing as this to their own son. Weren't they the same Ma and Pa who once let a runaway slave hide in our hayloft for a week? And now hadn't they locked me into an apprenticeship that wasn't but one step removed from slavery? Who could find any sense in that? Up to then I don't think I'd ever hated any people that I loved so much.

CHAPTER THREE

J

UST WHEN MY LOWER LIP WAS HANGING

all quivery, things took an unexpected turn for the better and I made me a friend. He must have been watching my goodbyes, 'cause without introductions he stepped up and reminisced, "I still recall the day I tried out my own wings."

Looking over, I faced a gentleman dressed like someone who owned ten plantations, and not little ones either. Beneath his black top hat was a head of black hair and a black goatee that was even shinier than his black boots. His voice was low and easy and didn't have no cracker crumbs to it.

"Beg pardon?" I said.

"Son," he answered, "there's no reason to go begging for anything around me. I'm the fellow you've heard of who believes in giving away the best of what he's got. It will only come back a hundredfold. That's my philosophy. What's yours?"

Well, he'd flummoxed me good with such talk, to say nothing of overwhelming me with the fine cut of his clothes and the lordly line of his nose and the generous gleam of his blue eyes. His mouth was so full of handsome pearly teeth that it could have gone neck and neck with a king's. What's more, smack in the middle of the ruffliest white shirt I ever hope to see flashed a diamond stud that could have hypnotized a snake. Without thinking, I answered, "Staying clear of slivers. That's my philosophy."

Such talk tickled him hard. He laughed a bit and then started stroking his goatee and sizing me up real thoughtful-like.

"Name's Charles Larpenteur," he said, putting his hand out for shaking purposes, "though most call me Chilly. What'd your pa call you?"

"Zebulon Crabtree, sir." I gave him my best manly handshake.

I almost lost my hand in his, oversized as it was. Height-wise, he may have been smallish, but across the shoulders he was worth an ax handle and his paws were monsters.

"Most call me Zeb." I pulled my hand to safety. "Do you mind if we step back from the railing a ways?"

"Not at all, Zeb. Not at all."

He took a leisurely glance up and down the deck, as if on the lookout for someone, then waved me behind a cord of