Crude World (18 page)

The representatives of BP, Amoco, Pennzoil, Unocal and lesser outfits squeezed into this squalid box. Because the hotel’s services varied from sporadic to absent, the oilmen imported, on their corporate jets, things like breakfast cereals, printer paper and bottles of Johnnie Walker, so that they could enjoy a shot or four at the end of the day and not wonder whether it had been diluted with antifreeze by the waiters at Ho Bar. Phone lines were assumed to be tapped by the Azeri KGB or rival oilmen who wanted to know who their competitors were talking to and what they were saying. I visited Baku a few years ago and talked to oilmen who recalled the Intourist with an I-was-there horror—a visceral badge worn by survivors of momentous events. “We knew that all our rooms and all of our phones and all of our cars were bugged,” one told me. “We would have a conversation in a car and within twenty-four hours a friend would come up and tell us exactly what we said. We would do silly things, too—we’d say we needed to meet one of the heads of a political party but we couldn’t find him, and we’d just announce it in an empty room.” Because the walls were bugged, the

announcement was heard by the hotel’s eavesdroppers. “And twenty minutes later, the manager of the hotel would say, Would you like to meet with so-and-so?”

Sensitive documents could not be left in the rooms; everything of competitive interest was carried in locked briefcases or protected by guards standing outside the living quarters of executives when they had meetings elsewhere. No one could be trusted, including the ministers and bureaucrats who represented the government of the moment. Until Heydar Aliyev consolidated his hold on power in the mid-1990s, Azerbaijan endured a dismal reign of warfare, petty violence, utter poverty and a succession of leaders who were no better than Mafia chiefs. How do you negotiate in such circumstances? One of the representatives of the government was a shady Slovak businessman who was never seen without a pistol strapped to his waist—and who once pointed the gun at the head of an executive he was negotiating with. Confidential bids leaked out almost the moment they were presented to the government, because there was always a midlevel bureaucrat who augmented his meager salary by showing company X’s offer to company Y. “You make a supposedly confidential proposal and the next thing you know it has been shopped out by someone,” an executive told me. “It’s several Rolaids a day, every day.” Contracts would be signed one day, bottles of champagne would be opened in celebration—and within days the contracts would be declared null and a signing ceremony would be held with another company.

Like Alain, the executives I spoke with outlined the maddening pressures weighing upon them yet denied any personal unethical activity. Their competitors, they added quickly, were breaking the rules all the time. Apparently all oilmen in Baku were breaking the rules except the ones who were telling me that everyone was breaking the rules. What I knew for sure was that an Apple salesman would fail unless he adapted his sales tactics to the horrible box that awaited him at the doors of the Intourist Hotel.

The outside of the box looked different, of course.

On a February evening in 2003 I joined more than a thousand oil

executives in a Houston ballroom that was large enough for a jumbo jet or two. The pin-striped diners were served plates of mixed salad, grilled salmon and chocolate mousse by overworked waiters whose service was as gentle as cowboys heaving bales of hay to livestock. This was the gala evening of an annual oil conference at the city’s Westin Galleria Hotel, located in a massive mall that also featured a rink where Olympic skating champion Tara Lipinski trained. Drawn from across the globe, the men and just a few women in the chandeliered cavern constituted an oilpalooza.

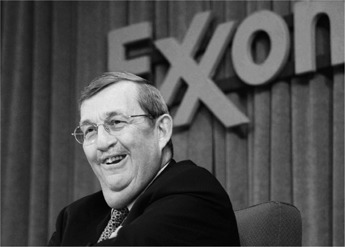

The attraction on this evening was neither food nor skating but a chemical engineer from South Dakota. Since 1963 he had worked for just one company, eventually becoming its chairman and chief executive. He made everyone else in his hard-bitten industry seem gentle. He was gruff even to members of Congress and scoffed at global warming long after scientists proved it. Greenpeace called the company he led America’s “number one environmental criminal.” He was superficially unappealing too, with a misshapen lip, an ample belly and a set of jowls that cartoonists would judge absurd. But in the oil industry you do not need to be pretty or kind to succeed, and this oilman had succeeded beyond anyone’s imagining. Lee Raymond had turned ExxonMobil into the largest and most profitable corporation in America. He was rewarded with an astounding $686 million in compensation during his thirteen-year tenure as chief executive, which breaks down to $145,000 a day, or more than $6,000 for every hour he worked, slept, ate or golfed.

Raymond fascinated me. Despite his stature and power, he was nearly unknown outside the environmental lobby, which despised him; the financial industry, which swooned over him; and the oil industry, which feared him. (Exxon’s executive suite was known as “the God Pod.”) Think of the tycoons who are part of the contemporary lexicon—Gates, Murdoch, Buffett, Jobs, Branson—and realize that absent from their ranks is the longtime leader of one of the most profitable multinationals of the twentieth century. Raymond was smart enough and secure enough to neither crave nor need publicity, which he knew would invite unfriendly questions. He did what he had to do, meeting

financial journalists to announce earnings, but little more. He turned down my requests to interview him.

I wanted to see him because he was not just in the highest echelon of his industry’s ruling class; he seemed its epitome. Oil firms employ millions of people as ditchdiggers, roughnecks, machinists, geologists, technicians, accountants, lawyers and consultants—a global army presided over by a commanding elite of larger-than-life executives. Like a nation or nationality, the industry has its particular belief system, its financial and political interests, its social layers and pecking orders. In some ways, it has the hallmarks of a political party

and

a religious movement. Use whatever metaphor you wish—senators, high priests or enforcers—it is impossible to know the oil industry without knowing the men who run it.

Mousse plates cleared, Raymond lumbered onto the ballroom stage. The crowd offered a round of applause that was akin to a handshake rather than a hug. In this industry, there was no need to feign love; grudging respect would do. Raymond’s lumpy, uneven physique imparted an off-the-rack look to his tailored suit. He made not a single attempt at humor, and he uttered every word with a metronomic drawl. He felt no compulsion to entertain or please.

His speech was an industrial mission statement. His listeners, who included government ministers, princes and CEOs, were reminded of how vital their work was, how underappreciated they were, how they must labor harder than ever, how the future will be grander than the already blessed present. A video screen enlarged Raymond’s presence to superhuman proportions. It was part Tony Robbins, part Billy Graham, with a whiff of a mumbling Leonid Brezhnev. Invoking a sacred industrial purpose, Raymond recited his version of the inspirational commandments of the oil world:

“We all have a tremendous opportunity and a responsibility to improve the quality of life the world over. Virtually nothing is made without our energy and our products.”

“Our industry’s best years lie ahead, surpassing even the greatest achievements of the century gone by.”

Lee Raymond earned $686 million in his thirteen-year tenure as chief executive of ExxonMobil

.

“We condemn the violation of human rights in any form, and believe our stand on human rights sets a positive example for countries where we operate.”

“It is almost impossible for someone who is not in the industry to begin to understand the magnitude of the industry and what we do.”

The audience’s reaction was ritualized, less a genuine wave of applause than an obligatory simulation. I was reminded that in this brutal industry, it was best to save your enthusiasm for crushing a rival rather than congratulating him.

The court building in Odessa, Texas, is a nearly windowless horror, designed in the 1960s by local architects who followed the Brutalist style popular at the time. If the building could talk, it would say there is no such thing as too much concrete or too little sunlight. I stepped inside on a summer day, seeking illumination that was neither solar nor fluorescent. I wanted to learn about the oil industry’s tendency to cut corners even in its own backyard.

Odessa is at the center of the Permian Basin, the great oil reservoir of west Texas. The city, with a population of nearly 100,000, has a love-hate relationship with its roughneck past. The cliché is that if you want to raise kids, do so in nearby Midland, and if you want to raise hell, do it in Odessa. When I visited, the town was less wild than it used to be, focusing more on economic development and high school football than tequila nights that ended in brawls and broken teeth. A museum, dedicated to all things presidential, emphasized the local oilmen who became the forty-first and forty-third presidents, George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush; visitors could pick up complimentary maps pointing them to the Odessa and Midland homes where the Bushes lived. Midland had proudly created its own Petroleum Museum, which claimed in its brochures to be “the nation’s largest museum dedicated to the petroelum industry and its pioneers.” If there was a place Big Oil might call home, where it would behave with conscience, it would be Texas, its petromanger.

Workers on an offshore oil platform

At its peak in the 1960s and early 1970s, output in the Permian Basin was 1.8 million barrels a day, pulled from a swath of mesquite plain that measured roughly 250 by 300 miles. Back in those days, west Texas was the Saudi Arabia of oil. At one point, the bonanza reportedly turned Midland’s Rolls-Royce dealership into one of the world’s busiest. But as the Permian Basin passed its prime, the big companies moved on, selling out to smaller firms. By the 1990s, with prices and output tumbling, the office towers in Midland that had once housed Exxon, Mobil, Gulf and Shell were vacant, not a tenant anywhere—tombs touching the sky. Those hard years turned bitter when people concluded that “the majors,” as the big companies were known, had stolen from them.

It was at the county clerk’s office in the Odessa court building that I learned about the alleged plundering. A lawsuit filed in 2003 accused Exxon, Chevron, Shell and nearly a dozen other firms of a decades-long conspiracy to avoid royalty payments on oil they extracted from

public land. In the nineteen-page complaint, the words “fraud,” “fraudulent” and “defraud” appear more than two dozen times. I was accustomed to hearing of predatory corporate behavior in Africa and the Middle East, but this was startling—a major lawsuit against Big Oil in its backyard, and the suit wasn’t the work of Greenpeace. It had been filed by the county government, with similar suits filed by nearly a dozen other municipalities in the Permian Basin.

Texans

were accusing Big Oil of stealing from

Texas

. And the accusers weren’t Austin liberals but oil-patch Republicans, as pro-business as possible.