Crude World (33 page)

Chávez did not just order PDVSA to boost its community spending by a few percentage points; he turned the firm into the engine of revolutionary change. PDVSA allotted more to its social projects in 2006—nearly $10 billion—than to its operations ($5.9 billion). In a sense, it became a development agency with oil wells. No other oil company, whether publicly traded or state-owned, spent nearly as much on non-core programs. In Saudi Arabia, Russia and other oil countries, state-owned firms tend to have modest social programs. Their surpluses are transferred to the Treasury and distributed to ministries that chase the holy grail of sustainable development. Usually they fail. You can build colleges, as Saudi Arabia did, but that doesn’t mean the degrees will count for much or that jobs will await the graduates.

Chávez was betting, almost literally, that an oil company would succeed where government ministries might not. PDVSA went from one extreme—disassociated from the government it was supposed to serve—to the opposite extreme of taking over the government’s duties. I knew that villagers in the Niger Delta would be delighted if Shell or its government-owned partner would provide the education, electricity, medical care and jobs that the negligent and corrupt government

did not offer. But it was hard to imagine how oilmen might do better development work than a government’s development experts. Oil companies should certainly provide funding and support to official efforts, as well as fight corruption and waste. But replacing a government seemed a doomed concept. As Toro-Hardy said in his exasperated way, “Oil companies should do more, but they should not change their mission. Now, instead of investing in its own projects, PDVSA is investing in housing and social programs. This is very nice, but it’s not for an oil company.”

In Venezuela, it was as though a well-meaning doctor was using the wrong instruments and wrong procedures to operate on a sick patient. Even during the boom years, signs of failure were ample—price controls on foodstuffs were leading to shortages, and the government was spending so much on subsidies that it was running into deficit problems, which is a striking achievement when large amounts of revenues are being received from oil sales. Chávez’s policies, intended to break the resource curse, seemed likely to prolong it. “I am not defending the previous governments,” Toro-Hardy said as he walked me out of his private sanctuary. “They did an awful job. But giving away money is not going to solve people’s problems. We have a saying here: ‘Bread for today and hunger for tomorrow.’”

When oil prices slid back to the double digits, Chávez’s popularity began to slide, too. He didn’t have as much money to throw at the country’s problems. An opposition candidate even won election as mayor of Caracas in 2008. Magic shows can obscure reality but cannot make it disappear.

One day, my journey into the twilight of oil took me to San Gorgonio Pass, in southern California. The mountains around the desert pass rise to more than ten thousand feet, but they are not the most dramatic sight. The pass, one of the breeziest spots in the state, is home to a wind farm that consists of about three thousand turbines spread over five thousand acres. Some turbines are eighty feet high, others rise above three hundred feet, and together they can produce electricity for hundreds of thousands of homes. Set against the blue sky and the brown desert, in rows of rotating white arms that glint in the sun, the turbines have the appearance of futuristic totems waving at us, luring us forward.

The farm is located at the intersection of the I-10 Freeway and Route 62, which leads to a Marine Corps base at Twentynine Palms. This makes San Gorgonio a symbolic as well as a geographic crossroads. In one direction lies a bastion of American military power that upheld, in the last century, an economic system dependent on fossil fuels. This direction leads, or should lead, to our past. In another direction, the one symbolized by windmills rather than howitzers, lies our future.

Though oil provides fuel for our cars and warmth for our homes, it undermines most countries that possess it and, along with natural gas and coal, poisons the environment. We need to find another way. Because I am hopeful, I have not been speechless when people have asked me, “How do we stop the human, terrestrial and climate damage of fossil fuels?”

I tell friends and strangers about the importance of conservation. I stress the benefits of renewable energy. I note that coal plants are particularly deadly—and that we should build no more of them. Although I haven’t raised my own vegetables, I mention the importance of locally grown food and, in the developed world, meals that involve lesser amounts of meat. Of course I emphasize the importance of transparency in oil and gas deals.

This isn’t always what my questioners want to hear, though. They want a new answer, something they haven’t heard before, a fresh solution to monumental problems that other answers haven’t seemed to solve. A new technology, a new … something. But the good news, which they haven’t understood, is that we already possess most of the answers we need. We have technologies and policies that can, to borrow a phrase from a previous generation, change the world. One of the reasons we face a world melting into violence—and just plain melting—is that for several decades we have refused to act on the answers within reach. Do you remember the solar panels President Jimmy Carter installed on the roof of the White House in 1979? If you don’t, that’s probably because Carter’s call for “the moral equivalent of war” in the realm of energy went nowhere and President Ronald Reagan took down the panels several years later. Yet solar power remains an answer that can help us survive into the twenty-second century.

Wind farm in the San Gorgonio Pass near Palm Springs, California

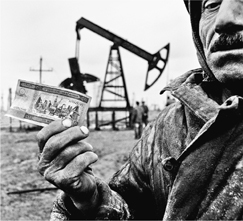

A worker at the Bibi Heybat oil field in Baku, Azerbaijan, holds the local currency

.

There are other answers.

Some of this book focused on corruption in countries that have the misfortune to possess large amounts of oil. A remedy is at hand. It’s not a complete one, but it could, if enacted in full, return a measure of health to sick economies and polities.

It is known as Publish What You Pay and is being promoted by a nongovernmental organization of the same name. It means what it sounds like. Few companies and governments disclose the contracts they sign or the payments they make and receive. This creates a cloud of confidentiality in which bribes can be paid, sweetheart deals can be struck and billions of dollars can be embezzled. A secret contract is a harbor for crooked executives and politicians.

PWYP would compel companies and governments to publish the financial terms of their contracts. A related though less aggressive campaign that already involves some governments is known as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, and though its goals are similar to PWYP’s, it promotes voluntary codes rather than compulsory ones.

A few companies have published some figures, and a handful of nations have publicized a portion of their receipts. But the steps taken so far are extremely small. Today, people in Angola, Equatorial Guinea, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Russia, Iraq, Iran, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and most other energy-rich countries have almost no way of knowing, even though their leaders might have signed on to EITI, how much money is paid to their governments or the terms of payment, and almost no way of confirming that energy revenues go into reliable accounts that are beyond the reach of corrupt leaders. Full transparency would help remedy these problems.

The enforcement of prevailing laws is a remedy, too. There is a piece of philosophy from the frontier days of America: If you are involved in a shootout, you should not have any bullets left at the end. Anti-bribery laws in America and Europe are unevenly enforced. For instance, there has been no sanction against the energy companies that made dubious payments in Equatorial Guinea to President Obiang and his family. Riggs Bank, which helped hide Obiang’s money, was forced to pay millions of dollars in fines, although its principal owners, members of the Allbritton family, escaped indictment and were able to sell their bank. Riggs, however, was a niche institution with less clout in Washington than, say, Exxon or Chevron, which have not been indicted or fined for their questionable dealings. There have been some enforcements lately, of course—Halliburton paid substantial fines for its bribery in Nigeria, and Siemens A.G., the German engineering firm, paid fines of $1.6 billion in America and Europe after admitting to a global bribery spree. But much more can be done. Every year U.S. prosecutors issue only a modest number of indictments under the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act. Authorities in Europe and Asia have proven loath to file bribery charges except in the most egregious of cases. The law is a weapon that rarely leaves our holster.

At the risk of sounding even more old-school, I’ll mention an additional remedy we need to impose: social values. Even when enforced aggressively, laws alone cannot do everything; they need to be complemented with social pressure that opposes unethical and exploitative profiteering. Ida Tarbell noted this a century ago, in her famous exposé of the extortionary methods used by John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. Tarbell argued that part of the problem resided in society’s ambiguous reaction to Rockefeller’s law-shaving, fortune-making success. “There is no cure but in an increasing scorn of unfair play—an increasing sense that a thing won by breaking the rules of the game is not worth the winning,” Tarbell wrote. “When the businessman who fights to secure special privileges, to crowd his competitor off the track by other than fair competitive methods, receives the same summary disdainful ostracism by his fellows that the doctor or lawyer who is unprofessional receives … we shall have gone a long way toward making commerce a fit pursuit for our young men.” Tarbell, who was right one hundred years ago, is right today.

Just as individuals in the developed world need to be partisans of a new ethos, their governments need to encourage good governance in unstable nations that are rich only in resources. Where civic groups and multiparty systems do not exist or are weak, our governments should lobby for them so that grievances can be settled through discussion rather than violence. Democratic governments should not support dictatorships whose oppression foments rebellion. War-crimes trials should be pursued against armies and militias that commit atrocities (as many do in wartime). Development assistance should focus on reducing the reliance on mineral exports like oil.

On paper, these policies have been adopted by democratic and even nondemocratic governments in the developed world, but in practice the situation is quite different. In Azerbaijan, Angola and a barrelful of other dictatorships, support for democratic change has been minimal. On the economic side, development policies pursued by the World Bank and the IMF have tended to do more harm than good in recent decades, leading to heavy debt loads and industrialization programs that harmed all-important agricultural sectors. We have plenty of answers; resolve is what we lack.