Crude World (6 page)

Let’s begin at Marathon’s natural gas facility, the one whose immense flares brightened (and polluted) the night sky. Little of the

$1.5 billion Marathon and its minority partners spent on the facility entered the local economy because the plant was built by thousands of foreign workers who lived on the construction site and sent their paychecks home to Manila and Houston. Even for manual labor—digging ditches and the like—workers were flown in from India and Sri Lanka. I wouldn’t have understood the economic logic had I not been driven around the plant by its genial manager, Rich Paces, a Texan, in his SUV.

As we moved around the site I noticed that almost all the workers were South Asian, while managers were American or European. I knew that Equatorial Guinea’s labor force included few college-educated managers, but there was no shortage of young men who could pound nails. Why weren’t they working here? Paces explained that the Indians and Filipinos had previous experience on large projects of this sort, so they required little instruction. They knew how to use welding torches, they knew how to avoid injury from the heavy machines on the site, and they could be counted on to work twelve-hour shifts without complaint. Also, they were not hobbled by malaria or yellow fever, which were rife among the native population. The few locals working at the plant were hired under a quota written into the company’s contract with the government.

“We’re under contract to hire them, and it’s the right thing to do,” Paces said. “But if we didn’t have those limitations, we’d entirely staff it up with low-cost Filipinos and Indians.”

The plant—like many oil installations in the developing world—could have been on the moon for all the benefit it offered local businesses. Thanks to just-in-time supply networks that span the globe, Marathon saved money by importing what it needed rather than working with unfamiliar local suppliers. Instead of buying cement from a Malabo company that might not deliver on time, Marathon built a small cement factory on the construction site. Raw materials were imported, and the factory would be dismantled when construction ended. The trailers in which the Asians lived were prefab units—no local materials or local labor had been used to build them. The plant had its own satellite phone network, which was connected to the company’s

Texas network—if you picked up a phone you would be in the Houston area code, and dialing a number in Malabo would be an international call. The facility also had its own power plant and water-purification and sewage system. It existed off the local grid.

“Almost everything has to be imported,” Paces explained.

How about paint? I asked.

“Imported, sure,” he replied.

Portable toilets?

“Yes.”

Equatorial Guinea had a lumber industry, so I asked whether the wood, at least, was local.

“No, imported.”

Food?

“Most of it gets imported.”

Construction cranes?

“You have to be self-sufficient out here.”

I pointed to the small rocks that had been lined up to denote the shoulders of a dirt road on the site.

“Those are local rocks, but importing them would be cheaper,” he said.

That night, I strolled through the center of Malabo and found a few hubs of local job creation. Their names were La Bamba and Shangri-La, and they were open-air bars that played country music to attract the roughnecks from Texas and Oklahoma. The teenage girls who swarmed these establishments were dressed in skirts made for whistling at. The oilmen called them “night fighters” because they battled each other for the chance to spend an evening with one of the rich foreigners. As I walked past La Bamba, several girls trotted out of the bar to chat me up. The men in Malabo might not find jobs in the oil industry, but it was clearly possible for their desperate sisters to earn a few dollars.

The oil companies provided few jobs to local people, but they were paying royalties—at least in the hundreds of millions of dollars a

year—for the privilege of extracting and selling Equatorial Guinea’s hydrocarbons. Where was

that

money going?

It was no secret that Obiang lived far beyond the means of his official salary. He belonged to the class of dictators who do not feel the need to obscure the comfort they grant themselves. Conspicuous consumption is a manifestation of greed as well as a way to project power. In a country like Equatorial Guinea, anybody could kill you with a gun, but how many people could afford to live in a mansion with

two

tennis courts? Obiang had built, along the well-traveled road from the airport into Malabo, several mansions for himself and his wives. Although the dictator was not always in evidence—the airport road was closed to other vehicles when his motorcade traveled on it—his wealth was well advertised. He bought, for $55 million, a Boeing 737 in which the bathroom fixtures were gold plated. When the plane was flown into Malabo’s airport, Obiang was on hand to inspect it and boasted to reporters, “This plane elevates the image of our country in the developing world.” His indulgences were almost modest compared with those of his eldest son, Teodorin, who bought luxury homes in at least two countries, including a $35 million estate in Malibu. To round out the portrait of playboy extraordinaire, young Teodorin dated the rapper Eve and invested in a hip-hop label, TNO Records. For a week-long Christmas cruise, Teodorin rented, for a reported $700,000, a monster yacht that belonged to Microsoft cofounder Paul Allen. It should be noted that Teodorin’s official salary at the time, as the minister of forestry, was $48,000 a year.

The first family could not spend all the money coming in from the oil companies, hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Yet little of this bonanza was used for improving the lot of ordinary people. When I visited the minister of education, I noticed that he worked out of an office that had a bare light bulb for illumination and a couch the Salvation Army would have rejected. The most valuable item in his office was his Rolex, which suggested that his needs received more attention than his ministry’s. If he required more light, it seemed he would need to buy a bulb himself or swipe one from a subordinate. It was like that

in every government building I visited, including the few schools that existed at the time; there was dilapidation at every stop. More than a decade after oil’s discovery, nearly half of the children under the age of five remained malnourished, few households had running water or electricity, and soldiers at checkpoints continued to demand bribes—

“cerveza”

they would say to their victims (including me). There was little choice but to hand over beer money and hope for better times. “The staggering increases on paper stand for little,” a British report noted. “Equatorial Guinea’s wealth is concentrated in the hands of a tiny elite, so oil revenues do not benefit the majority and do not stimulate the economy as a whole.”

The money trail is no mystery. Old ladies and petty criminals can hide their savings in mattresses, but oil dictators cannot do the same with hundreds of millions of dollars. Stealing oil revenues is not like holding up a grocery store. You need to get the oil and gas out of the ground, you need to ship and sell it to foreign markets, you need to put the revenues into bank accounts, and you need to find ways to share some of this money with the family and friends who are the political elite that help run your country and keep you in power. You need, in other words, a lot of help. Usually this can be done without indictment; offshore banking is made for such tasks. But Obiang made a mistake that allowed the rest of the world to understand the dynamics of making a nation’s oil wealth disappear. Instead of stashing the millions in a numbered Swiss account, he selected a niche bank in Washington, D.C., that was willing to abet his plan but was incompetent at doing so.

A ritual indulged in by men of great wealth is the luncheon with their bankers. The wealthy client is ushered through the bank’s private entrance and is conveyed in a special elevator to a wood-paneled dining room, where he is flattered and fed like a king. If the client makes a joke, the laughter is fulsome. If he suggests a certain investment priority, his opinion is received as brilliant. This, more or less, was the white-glove treatment granted to Obiang by Riggs Bank, which for more than a century had offered its discreet services to the powerful and well connected in Washington, D.C. When Obiang visited the

United States in 2001, a lunch was held by the bank, where Obiang had become, thanks to enormous deposits into his accounts from Exxon and other oil firms, the largest client. His fawning hosts—the bank’s president and other executives—sent him a grateful follow-up letter, which congressional investigators later obtained.

“We hope this letter finds you well and rested after your last busy trip to Washington,” their missive began. “We would like to thank you for the opportunity you granted to us in hosting a luncheon in your honor here at Riggs Bank.” The letter expressed their “gratitude” for the chance to serve Obiang and promised to “reinforce your reputation for prudent leadership and administration as you lead Equatorial Guinea into a successful future.”

Obiang started his relationship with Riggs in 1995, when he decided that it would be easiest to use an American bank as a parking spot for the money he was beginning to receive from American oil companies. After all, why go to the trouble of using a shady Swiss outfit when a respectable American establishment was willing to do the job? Obiang assumed that his solicitous bankers at Riggs could handle his affairs in a way that would defer inconvenient questions from the U.S. Treasury Department. Obiang and his family and his associates

opened sixty accounts at Riggs, some for official purposes, others for personal affairs. Deposits in those accounts reached $700 million. In tandem, Obiang and companies he owned opened accounts in countries with bank secrecy laws—the kinds of places where money goes to disappear for good—and filled those accounts with funds that came from Riggs, which acted like a traffic dispatcher in forwarding its clients’ money.

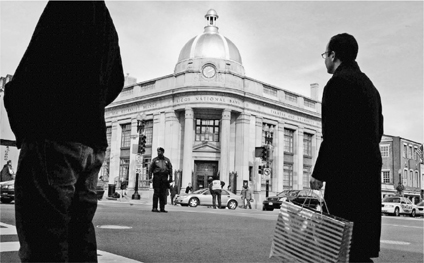

Riggs Bank in Washington, D.C

.

The primary Riggs account, known as the “oil account,” was where energy companies deposited royalty payments, and this account often held tens of millions of dollars at a time. It was used as a holding place for the money before it was transferred into other accounts at Riggs and elsewhere. There is no suggestion that payments into this account were bribes—the funds were owed to Equatorial Guinea by the oil companies—but the companies showed no interest in knowing what happened to this money. They did not seem to care that their payments were being handled in a fashion that screamed theft: the oil account at Riggs was controlled not by Equatorial Guinea’s government but by its president. (Imagine a company making its tax payment not to an account controlled by the IRS but to an account controlled by Barack Obama.) Obiang’s regime wired—without objection or scrutiny from Riggs—$35 million from the oil account to mysterious companies in banking havens with strict secrecy laws.

Then there were the “investment accounts” of Obiang’s regime. In 2003, the value of these accounts fluctuated between $300 million and $500 million. In effect, these were Equatorial Guinea’s financial reserves—the money that was gained from oil sales. It is unusual for the bulk of a country’s financial reserves to be held in a private foreign bank, especially a relatively minor one like Riggs. And it is even more unusual for transfers or withdrawals from these accounts to require just the president’s signature. Obiang actually did relatively little with them, aside from occasional transfers to the accounts in banking havens. Instead of being invested in schools or hospitals or light bulbs for the minister of education’s office, and while his compatriots died of malaria and hunger-related diseases, most of the money stayed at Riggs.

On occasion, the situation resembled a Charlie Chaplin movie. The Riggs banker who oversaw the accounts, Simon Kareri, twice went to the Equatorial Guinean embassy, a mile from his office, to pick up suitcases that weighed sixty pounds and contained $3 million in plastic-wrapped stacks of hundred-dollar bills. He dragged them back to Riggs and deposited their contents unquestioningly into one of Obiang’s accounts. (“Sir,” Kareri wrote in a memo to his superior, “I wish in due course you will get to know the President of Equatorial Guinea and witness his simplicity first hand.”) The bank also received cash deposits of more than $1.4 million into accounts belonging to one of Obiang’s wives. In those cases—as with other large cash deposits—Riggs did not file timely or accurate “suspicious activity reports” to regulatory authorities, as required whenever a bank suspects or should suspect that a transaction might involve illicit activities. Riggs was caught up in an age-old fever. In an e-mail, a senior Riggs banker excitedly predicted more deposits from Equatorial Guinea and explained, “Where is this money coming from? Oil—black gold—Texas tea!” It was such a free-for-all that Kareri transferred more than $1 million into an offshore company he controlled. It appears the dictator who was siphoning money from his country was himself being pickpocketed by his banker.