Curveball (23 page)

Authors: Martha Ackmann

That July,

Ebony

magazine published a five-page story and photo spread on Toni that unfortunately did not help her efforts to be viewed as a professional baseball player. The feature had been in the works for several months and included photographs from spring training as well as staged shots of Toni washing windows at her home in Oakland, stepping out on the town, and receiving a rubdown from her husband. “Toni Stone is an attractive young lady who could be someone’s secretary,” one caption read. The article was a mixture of fact and fabrication. Her years with the Saint Paul teams, the San Francisco Sea Lions, and the New Orleans Creoles were accurately presented, but the story also included false or misleading details made to enhance her education and femininity. “She studied for a time at St. Paul’s “McAllister [sic] College,” the article said, and she is “an excellent housewife and cook.” Perhaps eager to please Syd Pollock or simply wanting to appear higher paid than she was, Toni told reporters that for two years she had refused Pollock’s offers to join the team. “I felt I wasn’t ready, but when he said $12,000 for the season, I reached for my fountain pen.” The feature may have gained Toni notoriety, but it treated her desire to play baseball as a curiosity. It certainly did not help break down or even identify the serious barriers she faced. Years later, she looked back on the feature as a mistake and wished she had not participated in it. “I was young,” she said, “and they were capitalizing on me.”

66

Second thoughts about her participation in the

Ebony

feature may have led Toni to be less available when a woman reporter in St. Louis wanted to sit in the dugout with her in the July game at Busch Stadium and talk about what it meant to be a woman in a man’s world. As she stepped out of the first aid room—her improvised locker room for changing into her uniform—Toni saw the reporter waiting for her. “Oh, no,” she said, refusing to be interviewed, “not until after I have played.” She’s superstitious that way, Buster said. If the team wins with her sitting on the right side of the dugout, she’ll sit there every night, he explained. Toni coached first base during the initial game of the doubleheader, and was animated with Clown runners on first and third. But when the Monarchs ended the rally with a double play, Toni stormed back to the dugout, sputtering to no one in particular. “You bring them in. I can get them on base but not farther.”

67

Also watching the game from the dugout was Deseria “Boo Boo” Robinson, who had joined the team four days earlier as another Toni understudy. Robinson, a twenty-three-year-old former player for the Capehart team, a semi-pro squad from Fort Wayne, Indiana, appeared shy and nervous and looked to Buster every time the reporter asked her a question. Like Doris Jackson, who had joined the Clowns two weeks earlier in Washington, D.C., Boo Boo would be gone before she had time to make an impression.

Game two was terrible for Toni. She committed two errors and struck out twice. And even worse, Syd Pollock had come in from New York to watch. Back home in Tarrytown, his “Girl Player” folder was thick with letters of inquiry and applications.

68

With all the publicity Toni was receiving, other women wanted to play with the Clowns or take her job. Despite the rousing ovation fans gave Toni at Busch, she could not forgive herself the mistakes. After her second strikeout, Toni returned to the bench and started to cry. “She takes the game too seriously,” Pollock said. “She knows the crowd came to watch her give a show as the only woman in the league and she was trying awfully hard to make one for them.” Trying too hard was a criticism Toni had heard before. She sat alone on the bench for the rest of the game and remained “very quiet,” the reporter noted.

69

On Saturday, August 8, Big Red was nearing Jefferson City, Missouri, en route to a doubleheader in Kansas City. The matchup would be the second time since Opening Day that the two teams had met in Blues Stadium, and Bunny expected another big crowd. Toni and the Clowns were tired from a quick jump to Buffalo and Pittsburgh earlier in the week and were trying to nap as they always did when the bus droned on. Another line of fierce storms had rolled through the Midwest two days before, and the damage still could be seen. A few hours to the east, hurricane force winds had knocked down a highway patrol radio tower in St. Louis. In a business district, glass from broken windows littered the sidewalks, and the ground was still saturated from half an inch of rain that had fallen in five minutes. The downed trees and debris created a “jungle-like scene.”

70

The Clowns were glad that the bad weather did not seem to threaten their game in Kansas City. They were eager to play, and the season was turning around for them. Now in second place in the second half of the Negro League season, they were playing ball well above .500. Syd Pollock had returned to New York after the St. Louis trip and gotten busy with press releases, using a new phrase for promoting Toni. “She is murder minded in her effort to aid the team,” he wrote, “a tough sister on defense [who] asks no odds from men hurlers when she goes to the plate.”

71

Hyperbole again blurred the line between fact and a good phrase.

Everyone on the bus was in his usual seat: Ted Richardson, the next day’s pitcher, slept in the long back seat, stretching out his legs so they wouldn’t cramp. Bunny Downs sat near him where he could eat his ritual meal in peace—a concoction of pork and beans, sardines, onion, and bread. Spec Bebop, the team’s dwarf comedian, rarely sat. If he perched on a bus seat, his short legs did not reach the floor and his limbs became numb, so Bebop stood most of the time.

Charlie Rudd, a former driver for the Birmingham Black Barons, was at the wheel. He had relinquished driving to Chauff some years ago but pitched in when the Clowns needed him. After four months on the road, Chauff welcomed relief from four-hundred-mile days. Already the team had been driving for hours that morning. Around ten-thirty, they approached the Osage River Bridge, a two-lane crossing south of Jefferson City. As usual, the milk can sentry sat perched next to Rudd, but there weren’t many directions to call out—just a narrow country bridge over muddy water. As Charlie steered Big Red onto the bridge, he saw a panel truck at the opposite end, politely waiting to give him a wide berth. “Fashion Cleaners,” he read as he aimed the bus between the truck and the guard rail.

Behind the truck was a large tractor-trailer, its driver impatient that Fashion Cleaners had stopped. Unable to see what was holding things up, the tractor-trailer shifted into gear, swung around the cleaners’ truck, and accelerated onto the bridge. That’s when Milk Can saw it. By the time the tractor-trailer’s driver realized the Clowns bus was coming dead on toward him, it was too late. Charlie slammed on his brakes, but he couldn’t stop in time.

72

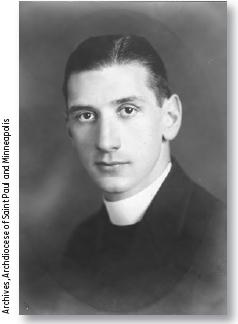

Father Charles Keefe.

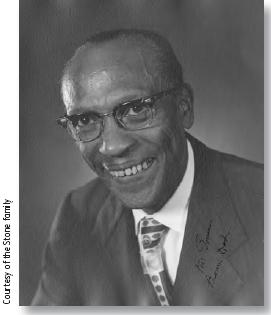

Boykin Freeman Stone.

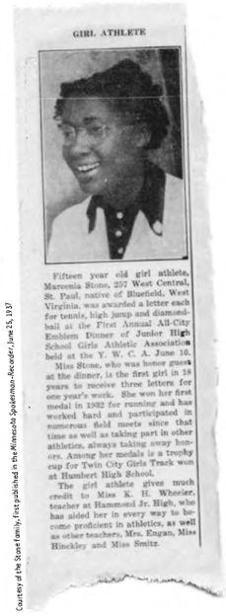

Tomboy Stone excelled in baseball, basketball, golf, hockey, ice skating, swimming, tennis, and track. One local newspaper reported that “Miss Stone” is “always taking away honors.”

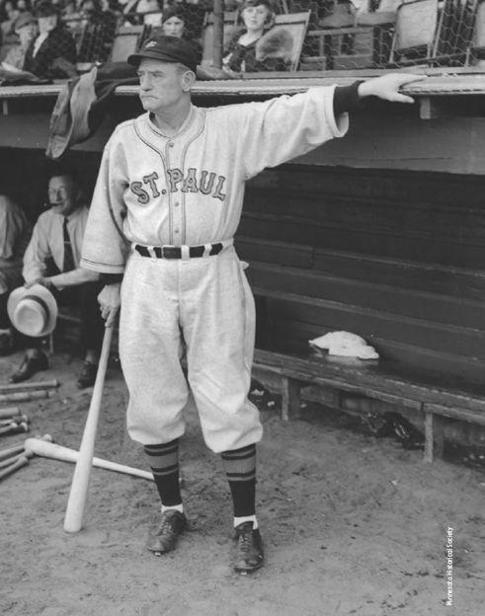

Charles Evard “Gabby” Street.

Jack’s Tavern, San Francisco.

Toni Stone on the San

Francisco Sea Lions, 1949.