Cyber Warfare (13 page)

Authors: Bobby Akart

Some argue that the term

act of war

is a dated one. The use of the terminology—

act of war

—was a more common term when used in conjunction with an Article 1 declaration via Congress. But the Geneva Conventions of 1949 actually dispensed with the requirement that war be declared before the rules of war apply.

During any discussion of whether a cyber attack is an act of war, the following questions arise:

When is a cyber attack an unlawful

use of force

under the United Nations Charter?

When can the victim state respond with physical force because the cyber attack qualifies as an

armed attack

under the U.N. Charter?

While the difference is a matter of semantics and far more relevant to the rest of the world, Washington does not distinguish between the two. The Tallinn Manual addressed several factors:

•Severity: How much damage did the attack cause?

•Immediacy: How quickly the consequences of the attack manifest themselves.

•Directness: How many intermediate steps had to occur between the attack and the consequences?

•Invasiveness: How much security did the attack have to bypass to cause its results?

•Measurability of effects: How easy is it to measure the damage caused?

•Military involvement: How involved was the military in carrying out the attack?

•State involvement: How involved was the state in carrying out the attack?

•Presumptive legality: Was the attack more akin to a military act, or was it merely propaganda, espionage, or economic pressure?

On one end of the spectrum are acts that don’t constitute acts of war, like espionage. On the other end are acts that do constitute a use of force—say, military aggression. It’s a relatively simple process to determine whether an act constitutes military force and, accordingly, if the victim nation has the right to respond.

“If you have a cyber operation that causes physical damage or injuries to a person, that’s an armed attack, and you can respond forcefully,” proponents of the Tallinn Manual say. “When a cyber attack doesn’t reach that threshold, things become more complicated. Everyone agrees that certain cyber operations are clearly not armed attacks, for example, cyber espionage.” Under these parameters, shutting down the national economy is probably an act of war, but short of that, it’s not certain. By example, the Sony attack would fall outside of the gray area and, therefore, did not constitute an act of war.

So when would a cyber attack constitute an act of war? Based upon the Tallinn Manual, the only cyber attack that could have constituted an armed attack was allegedly carried out by the U.S. and Israel—Stuxnet.

Instead of demanding retribution from the U.S. or Israel, Iran stayed quiet for two years—until the Saudi Aramco incident. As chronicled herein, while no physical damage resulted, it took Aramco several weeks to replace tens of thousands of hard drives to prevent further spread of the virus, causing significant disruption to the company. The next month, several significant attacks took down the websites of financial institutions in the U.S. and prevented bank customers from withdrawing funds. Both the Aramco attack and the financial system attacks were attributed to Iran. Even though two years separated the Stuxnet and Aramco/bank attacks, observers surmised that Iran was retaliating for the Stuxnet attacks.

Stuxnet is probably the closest thing we’ve had to an armed, physical attack. Stuxnet resulted in the physical destruction of the centrifuges. To achieve the same effect without the use of cyber tools, you would have had to go in and planted explosives or something similar to get that destructive behavior.

Stuxnet would have qualified as an armed attack, per the Tallinn Manual definition, and as discussed above, a cyber attack can be an armed attack where the effects are analogous to those that would result from an action otherwise qualifying as a kinetic armed attack. In other words, if a missile or bullet or explosive could have caused the damage—physical damage or personal injury—a cyber attack with the same result is an armed assault. Stuxnet, likely developed by the U.S. and Israel, met that test.

Despite Stuxnet qualifying as an armed attack, Iran never went to the United Nations Security Council to claim that the attack violated the U. N. charter’s prohibition on the use of force. Iran could have done so and sought assistance to respond to the attack. In cyber warfare, victim states are reluctant to make that declaration. If you call it an

act of war

, and later your surrogates carry out the same sort of cyber attack in retaliation, you may establish a precedent you don’t want to set. The response may be more than you bargained for.

Chapter Thirteen

If the U.S. Government doesn’t respond, might the company?

The next

world war

might not be a

war

at all.

The nature of cyber warfare – and whether the U.S. government would even be among the combatants – has become a daily discussion on news networks and within our government. Broadly speaking, the media and pundits are too quick to use the word

war

when it discusses harmful cyber activities.

If it’s just theft, it’s theft. If it’s espionage, it’s espionage. Neither theft nor espionage gives rise to an act of war.

War or not, increasing escalation is bound to produce some response, and as Washington struggles to defend the government from cyber intrusions, private companies have learned they cannot rely on protection from the government.

“Most companies have realized that the federal government is not coming to their rescue in the cyber sense,” said one cyber security analyst. “They are essentially on their own against organized criminals in Russia, against state-sponsored hackers in China, against groups like Anonymous, and sort of the various threats out there that might be trying to steal their data or take out their systems.”

Cyber security experts warn private sector companies not to strike back in the cybercrime sphere. Their theory is INTERPOL and the FBI already exists for the purpose of criminal investigations and, therefore, is fully aware that the cyber attack or vandalism is a crime. They suggest that the private sector shouldn’t retaliate against adversaries. They would be, in essence, paying their employees to become criminals. That is the whole

two wrongs don’t make it a right

theory.

If American firms start hacking foreign rivals in retribution, they’ll be committing the same types of crimes perpetrated upon them.

But should private companies put their fortunes in the hands of law enforcement or the military? It all comes down to trust, the U.S. Department of Justice representatives argue, and sharing information with law enforcement is the best method of bringing hackers and cyber terrorists to justice.

Many cyber analysts disagree. “Companies are not just going to keep taking this,” one expert warned in an interview with CNBC. “If the government is saying to them,

we can’t actually protect you, and we’re not necessarily going to go on the offense for you

, I think it’s only a matter of time before you see a company take matters into its hands and essentially go on the offense and take the fight back to the hackers.”

Will that fight take the form of U.S. companies hacking foreign firms, or even hacking foreign governments, such as China? All sorts of combinations are possible. Websites like HackersList.com, HireTheHacker.com, and CryptoHacker.com enable corporate IT departments to reach out and secure a team of cyber mercenaries to do their bidding. Sometimes, a victim wants to exact revenge or justice on their terms.

PART SIX

Is a Cyber War a Realistic Threat?

Chapter Fourteen

The Threat is Real

The very real threat posed to America by cyber warfare can be summarized by six central scenarios.

Over many decades, the U.S. has created the greatest military force the world has ever seen. But our research has proven that the biggest threat to national security comes from a computer with a simple Internet connection— not from aircraft carriers, tanks or drones. Having discussed the history of cyber warfare, its costs to both the private and public sectors, it's now time to address its increasingly important role in geopolitics.

Threats to the public sector

.

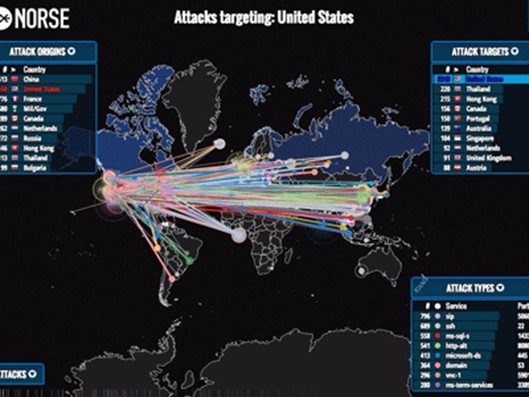

The U.S. government has been fending off cyber attacks for years. The federal government fends off a staggering eighty thousand cyber attacks a year. The wave of hacks in 2014 exposed the records of over fourteen million current and former officials dating back to the mid-eighties. Compromised information includes Social Security numbers, fingerprints, military records, job assignments and medical histories. Clearly, this is dangerous information in the hands of our adversaries and the teams of cyber terrorists they employ. There is good reason DNI Clapper ranks cyber terrorism as the number one national security threat, ahead of traditional terrorism, espionage and weapons of mass destruction.

Threats to the private sector

.

While rogue nation-states are interested in causing damage to governments, for some hackers and cyber criminals, cyber intrusions in the form of theft of intellectual property, personal data, and website defacement is enough to keep them occupied. The FBI notified nearly four thousand U.S. companies that they were the victims of cyber attacks in 2014. Victims of hackers ranged from the financial sector to major defense contractors to online retailers. Cyber security specialists report that almost ten percent of U.S. organizations lost $1 million dollars or more due to cybercrime in 2013 and another twenty percent of U.S. entities have claimed losses between $50,000 and $1 million over the same timeframe. According to the U.S, Chamber of Commerce, cyber attacks on the private sector costs the U.S. economy $300 billion per year. Some estimates claim that figure is closer to $445 billion, or a full 1 percent of global income, worldwide. It is projected that private firms around the world will spend $80 billion on cyber security in 2015 and that still won’t be enough.

Use of social media to issue threats and calls to action for terrorists

Social media has become a haven for cyber criminals and terrorists. As Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest have become an integral part of our lives, criminals now use these venues to commit cyber theft or as a method of communication for terrorists. Nearly one in three U.S. adults say one of their social media accounts has been compromised. Cyber security analysts believe ten to fifteen percent of home computers globally are already infected with viruses and malware. We live in a society where your online social media presence increasingly defines you to the rest of the world. Enterprising hackers with access to your accounts can cause untold damage to both your personal and professional reputation. In 2011, Facebook openly admitted that it was the target of six hundred thousand cyber attacks daily. After the unexpected uproar over these numbers, and in an effort to avoid scaring off potential users, Facebook hasn’t released official figures since. Vast terrorist networks have been established worldwide which use social media as a means to spread their doctrines to recruits or to issues calls to action for established members of their network. A recent attack on military recruiting centers in Tennessee was prompted by social media encouragement by ISIS.

Use of the cyber arena to spread propaganda to gain economic or military advantage

The Russians established a sophisticated propaganda machine under the supervision of its Internet Research Agency that waged a massive disinformation campaign in support for its annexation of Crimea and its invasion of Ukraine. These hired guns work hard, each one pumping out hundreds of comments and blog posts per shift. In addition, each hacktivist troll is reportedly required to post 50 news articles a day while maintaining half a dozen Facebook and more than ten Twitter accounts. It is not unusual for this machine to be used to gain a militaristic advantage as the Russians spread incorrect information throughout the online media.

Use of cyber attacks to conduct industrial espionage

While the Russians are notorious for gaining a military advantage through the use of cyber tactics, the Chinese are a determined bunch when comes to stealing valuable public and private sector trade secrets. The vast majority of America’s intellectual property theft is believed to originate from China. The Chinese employ elite hackers housed by the government throughout the world to mask their real affiliations. China’s goal has been to catch up with the U.S. in direct military strength. Washington already outspends China more than 4-to-1 in growing its military that makes achieving military parity very difficult. Rather than attempting to outspend the U.S., Beijing’s answer has been to focus instead on commercial and government espionage. The Chinese computer spies employed by the PLA have attempted raids on the networks of almost every major U.S. defense contractor and have stolen some of our nation’s most closely guarded technological secrets.