Daddy-Long-Legs and Dear Enemy (13 page)

Read Daddy-Long-Legs and Dear Enemy Online

Authors: Jean Webster

Just to live in the same house with Sallie's mother is an education. She's the most interesting, entertaining, companionable, charming woman in the world; she knows everything. Think how many summers I've spent with Mrs. Lippett and how I'll appreciate the contrast. You needn't be afraid that I'll be crowding them, for their house is made of rubber. When they have a lot of company, they just sprinkle tents about in the woods and turn the boys outside. It's going to be such a nice, healthy summer exercising out of doors every minute. Jimmie McBride is going to teach me how to ride horseback and paddle a canoe, and how to shoot andâoh, lots of things I ought to know. It's the kind of nice, jolly, care-free time that I've never had; and I think every girl deserves it once in her life. Of course I'll do exactly as you say, but please,

please

let me go, Daddy. I've never wanted anything so much.

please

let me go, Daddy. I've never wanted anything so much.

This isn't Jerusha Abbott, the future great author, writing to you. It's just Judyâa girl.

Â

Â

June 9th.

Mr. John Smith.

SIR: Yours of the 7th inst. at hand. In compliance with the instructions received through your secretary, I leave on Friday next to spend the summer at Lock Willow Farm.

I hope always to remain,

(MISS) JERUSHA ABBOTT.

LOCK WILLOW FARM,

August Third.

August Third.

Dear Daddy-Long-Legs,

It has been nearly two months since I wrote, which wasn't nice of me, I know, but I haven't loved you much this summerâyou see I'm being frank!

You can't imagine how disappointed I was at having to give up the McBrides' camp. Of course I know that you're my guardian, and that I have to regard your wishes in all matters, but I couldn't see any

reason.

It was so distinctly the best thing that could have happened to me. If I had been Daddy, and you had been Judy, I should have said, “Bless you, my child, run along and have a good time; see lots of new people and learn lots of new things; live out of doors, and get strong and well and rested for a year of hard work.”

reason.

It was so distinctly the best thing that could have happened to me. If I had been Daddy, and you had been Judy, I should have said, “Bless you, my child, run along and have a good time; see lots of new people and learn lots of new things; live out of doors, and get strong and well and rested for a year of hard work.”

But not at all! Just a curt line from your secretary ordering me to Lock Willow.

It's the impersonality of your commands that hurts my feelings. It seems as though, if you felt the tiniest little bit for me the way I feel for you, you'd sometimes send me a message that you'd written with your own hand, instead of those beastly typewritten secretary's notes. If there were the slightest hint that you cared, I'd do anything on earth to please you.

I know that I was to write nice, long, detailed letters without ever expecting any answer. You're living up to your side of the bargainâI'm being educatedâand I suppose you're thinking I'm not living up to mine!

But, Daddy, it is a hard bargain. It is, really. I'm so awfully lonely. You are the only person I have to care for, and you are so shadowy. You're just an imaginary man that I've made upâand probably the real

you

isn't a bit like my imaginary

you.

But you did once, when I was ill in the infirmary, send me a message, and now, when I am feeling awfully forgotten, I get out your card and read it over.

you

isn't a bit like my imaginary

you.

But you did once, when I was ill in the infirmary, send me a message, and now, when I am feeling awfully forgotten, I get out your card and read it over.

I don't think I am telling you at all what I started to say, which was this:

Although my feelings are still hurt, for it is very humiliating to be picked up and moved about by an arbitrary, peremptory, unreasonable, omnipotent, invisible Providence, still, when a man has been as kind and generous and thoughtful as you have heretofore been toward me, I suppose he has a right to be an arbitrary, peremptory, unreasonable, invisible Providence if he chooses, and soâI'll forgive you and be cheerful again. But I still don't enjoy getting Sallie's letters about the good times they are having in camp!

Howeverâwe will draw a veil over that and begin again.

I've been writing and writing this summer; four short stories finished and sent to four different magazines. So you see I'm trying to be an author. I have a workroom fixed in a corner of the attic where Master Jervie used to have his rainy-day playroom. It's in a cool, breezy corner with two dormer windows, and shaded by a maple tree with a family of red squirrels living in a hole.

I'll write a nicer letter in a few days and tell you all the farm news.

We need rain.

Yours as ever,

JUDY.

JUDY.

Â

Â

Â

August 10th.

Mr. Daddy-Long-Legs,

SIR: I address you from the second crotch in the willow tree by the pool in the pasture. There's a frog croaking underneath, a locust singing overhead and two little “devil down-heads” darting up and down the trunk. I've been here for an hour; it's a very comfortable crotch, especially after being upholstered with two sofa cushions. I came up with a pen and tablet hoping to write an immortal short story, but I've been having a dreadful time with my heroineâI

can't

make her behave as I want her to behave; so I've abandoned her for the moment, and am writing to you. (Not much relief though, for I can't make you behave as I want you to, either.)

can't

make her behave as I want her to behave; so I've abandoned her for the moment, and am writing to you. (Not much relief though, for I can't make you behave as I want you to, either.)

If you are in that dreadful New York, I wish I could send you some of this lovely, breezy, sunshiny outlook. The country is Heaven after a week of rain.

Speaking of Heavenâdo you remember Mr. Kellogg that I told you about last summer?âthe minister of the little white church at the Corners. Well, the poor old soul is deadâlast winter of pneumonia. I went half-a-dozen times to hear him preach and got very well acquainted with his theology. He believed to the end, exactly the same things he started with. It seems to me that a man who can think straight along for forty-seven years without changing a single idea ought to be kept in a cabinet as a curiosity. I hope he is enjoying his harp and golden crown; he was so perfectly sure of finding them! There's a new young man, very up and coming, in his place. The congregation is pretty dubious, especially the faction led by Deacon Cummings. It looks as though there was going to be an awful split in the church. We don't care for innovations in religion in this neighborhood.

During our week of rain I sat up in the attic and had an orgie of readingâStevenson, mostly. He himself is more entertaining than any of the characters in his books; I dare say he made himself into the kind of hero that would look well in print. Don't you think it was perfect of him to spend all the ten thousand dollars his father left, for a yacht, and go sailing off to the South Seas?

44

He lived up to his adventurous creed. If my father had left me ten thousand dollars, I'd do it, too. The thought of Vailima makes me wild. I want to see the tropics. I want to see the whole world. I am going to some dayâI am, really, Daddy, when I get to be a great author, or artist, or actress, or playwrightâor whatever sort of a great person I turn out to be. I have a terrible wanderthirst; the very sight of a map makes me want to put on my hat and take an umbrella and start. “I shall see before I die the palms and temples of the South.”

44

He lived up to his adventurous creed. If my father had left me ten thousand dollars, I'd do it, too. The thought of Vailima makes me wild. I want to see the tropics. I want to see the whole world. I am going to some dayâI am, really, Daddy, when I get to be a great author, or artist, or actress, or playwrightâor whatever sort of a great person I turn out to be. I have a terrible wanderthirst; the very sight of a map makes me want to put on my hat and take an umbrella and start. “I shall see before I die the palms and temples of the South.”

Thursday evening at twilight, sitting on the doorstep.

Very hard to get any news into this letter! Judy is becoming so philosophical of late, that she wishes to discourse largely of the world in general, instead of descending to the trivial details of daily life. But if you

must

have news, here it is:

must

have news, here it is:

Our nine young pigs waded across the brook and ran away last Tuesday, and only eight came back. We don't want to accuse any one unjustly, but we suspect that Widow Dowd has one more than she ought to have.

Mr. Weaver has painted his barn and his two silos a bright pumpkin yellowâa very ugly color, but he says it will wear.

The Brewers have company this week; Mrs. Brewer's sister and two nieces from Ohio.

One of our Rhode Island Reds only brought off three chicks out of fifteen eggs. We can't imagine what was the trouble. Rhode Island Reds, in my opinion, are a very inferior breed. I prefer Buff Orpingtons.

The new clerk in the post-office at Bonnyrigg Four Corners drank every drop of Jamaica ginger they had in stockâseven dollars' worthâbefore he was discovered.

Old Ira Hatch has rheumatism and can't work any more; he never saved his money when he was earning good wages, so now he has to live on the town.

There's to be an ice-cream social at the schoolhouse next Saturday evening. Come and bring your families.

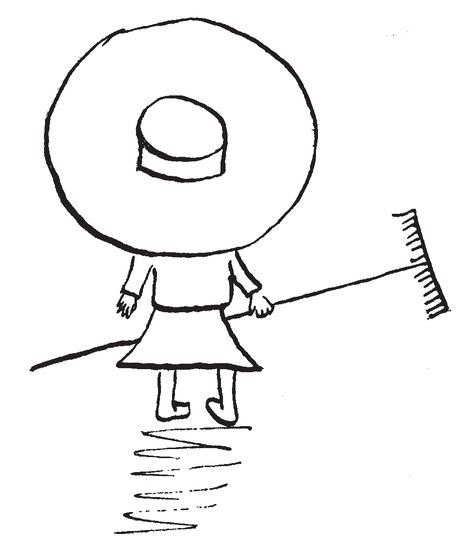

I have a new hat that I bought for twenty-five cents at the post-office. This is my latest portrait, on my way to rake the hay.

It's getting too dark to see; anyway, the news is all used up.

Good night,

JUDY.

JUDY.

Friday.

Good morning! Here

is

some news! What do you think? You'd never, never, never guess who's coming to Lock Willow. A letter to Mrs. Semple from Mr. Pendleton. He's motoring through the Berkshires, and is tired and wants to rest on a nice quiet farmâif he climbs out at her doorstep some night will she have a room ready for him? Maybe he'll stay one week, or maybe two, or maybe three; he'll see how restful it is when he gets here.

is

some news! What do you think? You'd never, never, never guess who's coming to Lock Willow. A letter to Mrs. Semple from Mr. Pendleton. He's motoring through the Berkshires, and is tired and wants to rest on a nice quiet farmâif he climbs out at her doorstep some night will she have a room ready for him? Maybe he'll stay one week, or maybe two, or maybe three; he'll see how restful it is when he gets here.

Such a flutter as we are in! The whole house is being cleaned and all the curtains washed. I am driving to the Corners this morning to get some new oilcloth for the entry, and two cans of brown floor paint for the hall and back stairs. Mrs. Dowd is engaged to come to-morrow to wash the windows (in the exigency of the moment, we waive our suspicions in regard to the piglet). You might think, from this account of our activities, that the house was not already immaculate; but I assure you it was! Whatever Mrs. Semple's limitations, she is a HOUSEKEEPER.

But isn't it just like a man, Daddy? He doesn't give the remotest hint as to whether he will land on the doorstep to-day, or two weeks from to-day. We shall live in a perpetual breathlessness until he comesâand if he doesn't hurry, the cleaning may all have to be done over again.

There's Amasai waiting below with the buckboard and Grover. I drive aloneâbut if you could see old Grove, you wouldn't be worried as to my safety.

Other books

Camp Nurse by Tilda Shalof

The One That Got Away by Lucy Dawson

Finders Keepers by Gulbrandsen, Annalisa

Stormbound with a Tycoon by Shawna Delacorte

Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke

Mrs. Tim of the Regiment by D. E. Stevenson

The black swan by Taylor, Day

Is It Wrong to Try to Pick Up Girls in a Dungeon?, Vol. 6 by Fujino Omori

Ryan's Protector - Lupinville 3.3 by Alice Cain

Nest of Vipers (9781101613283) by Sherman, Jory