Daily Life During The Reformation (14 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Village weddings that were once accompanied by drums,

bugles, and crowds of noisy people having a good time as they escorted

newlyweds home were beginning to be toned down by city ordinances to just a few

members of the family. The old, obscene, riotously enjoyable merriment of the

past had no place in solemn Christian ceremony.

Albrecht Durer,

Peasant

Couple Dancing

.

PATRICIANS AND BURGHERS

Wealthy families sat on the councils of most towns and had

a firm grasp on all administrative offices, made all decisions, using and

distributing finances as they saw fit. Guild and other taxes were exacted, but

as guilds grew and urban populations rose, the town patricians found themselves

confronted with increasing opposition. The burgeoning burgher class

incorporating well-to-do middle class citizens felt their increasing wealth

justified a claim to some rights of control over town administration and began

demanding seats on the town assembly.

They felt the clergy had failed to uphold its religious

duties. The opulence and laziness of Church officials aroused much ill will,

and the burghers demanded an end to the clergy’s privilege of freedom from

taxation as well as a reduction in their number.

URBAN WORKERS

Most urban workers were unskilled labor and hence not

organized into guilds. Some were petty retailers such as fishmongers, rag and

bone men, carters, unskilled construction workers, and the like.

Service trades were always a possible occupation for a

young urban man and included many professions from doctor, teacher, barber, and

notary to bathhouse keeper. These groups also formed guilds, but there was no

masterpiece to produce. In some places, examinations were required, however.

Special service trades might offer opportunities in some areas that were not

found in others; for example, some cities had licensed tour guides.

A trade depression, changes in fashion, or an invention

rendering traditional work methods obsolete could bring destitution to city

workers and to specialized communities such as the silk weavers.

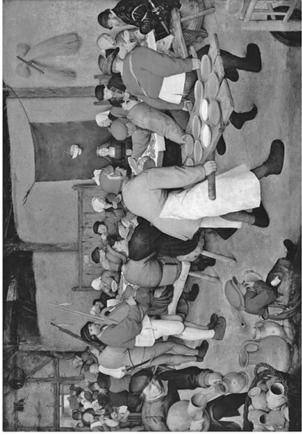

Peasant Wedding. Pieter Bruegel

the Elder, 1568. This painting depicts a peasant wedding scene. The feast is

held in a barn. The bride is seated in the center under the canopy. Flatcakes

are being brought in on a door that is off its hinges.

PEASANT WEDDINGS AND RELIGIOUS HOLIDAYS

Outside of the cities, life took on a different aspect when

the dreary, monotonous routine life in the villages was interrupted for

religious holidays or at marriages when the entire village would turn out to

partake in the festivities.

While the pipers played, they danced in the streets or

nearby fields. More wealthy peasants treated the festivities with great

generosity, spending a good portion of their income to entertain the locals. On

these occasions, coarse manners and heavy drinking were normal. While the

peasant consumed about a gallon of beer or wine per day, at weddings he went

well beyond this.

The marriage event was not unlike a church holiday that was

celebrated in a robust and irreverent manner with prodigious drinking that

often alarmed the clergy. By the sixteenth century, some 20 saints’ days were

observed each year involving religious festivities. Romping around the village

dressed in an array of costumes often made up of household utensils such as

pots and pans, beer barrel armor, tub hats, egg shell necklaces, ladles, and

other implements and accompanied by flutes, horns, and barking dogs, the din

was deafening, giving much delight, especially to the children. The threat of

danger was ever present, however, and men always carried knives or swords.

TIME AND WEATHER

The day for most rural dwellers within the Holy Roman

Empire, and indeed in most of Europe, was regulated by natural sunlight and by

the rhythm of the seasons. Artificial light from lamps was expensive, so oil

for lamps was carefully rationed. Men and women in both city and village worked

long days in summer and less in winter. By the sixteenth century, most cities

and small towns had a municipal clock that chimed the hours. These were

welcomed by the Church so that religious offices could be carried out at

approximately the correct time.

In divided communities of both Protestants and Catholics,

thorny problems arose over who would control the bell tower and ring it at the

appropriate time. Mass-produced calendars had been available since the

invention of printing, and these listed feast days, fairs, and phases of the

moon and were extremely popular at all social levels. But much confusion arose

over the changeover from the Roman Julian calendar, which was not so accurate,

to the Gregorian calendar that was more precise. According to the Romans, the

solar year had 365 and one-quarter days, and to counter this, a day was added

every four years to correspond to the seasons. These calculations, however,

were slightly off in the measurement of the solar year because a day was lost

every century. By the end of the sixteenth century, the calendar was 11 days

off with these computations, and on the day of the switch to the more precise

Gregorian calendar, October 4 became October 15. Most Catholic countries

adopted the pope’s new timetable immediately. Protestant countries were furious

at what they saw as the arrogance of the Vatican in its attempt to further its

influence even more and refused to adjust to it for the next century. Much

confusion ensued; a traveler leaving a Catholic city on January 1, on a two-day

journey, might arrive in a Protestant city on December 21 of the previous year.

Another reason Protestants objected to the new calendar was because it showed

Catholic religious days not appreciated in Protestant households.

A major factor in the lives of the peasants in the Holy

Roman Empire and all over Europe was the weather. Famines of catastrophic

proportions were always just around the corner. Harvest was an anxious time. A

severe hail storm, intense frost, or heavy rain and flooding could reduce the

yield to a fraction of what was required to maintain a family. Sometimes deep

snow came early, and harvest and transportation of the crop were hampered.

During the growing season, wheat, barley, vines, and other crops were always in

danger of a disastrous turn in the weather.

Drought, too, could be a major cause of crop failure as

rivers, streams, and wells dried up. Over a prolonged period of time, a chronic

shortage of water left the farmer helpless and desperate. It was often the

weather that left families starving, eating roots and boiled bark, and, unable

to pay their taxes, losing their homes. From property holder to landless

laborer was often an anomaly of the weather. In bad times, droves of miserable

humanity would shuffle to the church for a handout of a piece of bread or to a

larger city to seek work or beg on the streets.

Women and men working together

in the fields at harvest time.

Roxburghe Ballads

. Charles Hindley, ed.

(1874) vol. ii, 182.

TAXES AND THE LAW

The nobility and the clergy paid no taxes. The bulk of the

burden, therefore, fell as usual on the peasants. Princes often attempted to

force freer peasants into a state of near slavery through tax increases and the

introduction of Roman Civil law, more conducive to their desire for power since

it reduced all lands to private ownership and eliminated the feudal concept of

land as a trust between lord and peasant with the concomitant rights and

obligations. In adhering to the remnants of the Roman law code, they not only

heightened their wealth and position within the empire (through the

confiscation of property and revenues) but also their dominion over their

subjects.

Peasants could do little more than passively resist. Even

then, the prince now had absolute control and could punish them in any manner

he wished. Blinding or chopping off of fingers were common enough practices for

disobedience. Until Thomas Munzer and other religious radicals like him

rejected the legitimizing factors of ancient law and sought Godly law as a

means to rouse the people, uprisings remained isolated, unsupported, and easily

quelled.

Some ecclesiastics exploited their subjects as ruthlessly

as the regional princes. The Catholic Church used the authority of religion to

extort money from the people. In addition to the sale of indulgences, they

fabricated miracles, set up prayer houses, and directly taxed the population.

WOMEN

Within the Holy Roman Empire, as elsewhere, women had no

political voice, were not permitted to vote, and were not to serve on governing

bodies. Exceptions might be widows from noble families who controlled land

while their sons were still under age.

The average life span was 30 years for men and 24 for

women, and anyone who reached 40 was considered old. Women bore an average of

six or seven children, many of whom did not survive. Of those who did, 45

percent would die before the age of 12. About 10 percent of the men would never

marry, and around 12 percent of the women found themselves shut up in convents,

often unwillingly. Apart from marriage or religious orders, there were few

places in respectable society for a single woman.

7 - ENGLAND AND SCOTLAND

TUDOR ENGLAND

The

upper and middle classes in England became better off under the Tudors, the

royal house that ruled England throughout the sixteenth century. This was an

age of England’s growing naval strength, exploration, and increasing commerce,

and after about 1525, population numbers began to increase, while production

rose more slowly. Nobles and the upper middle classes invested money in land

and the economy and generally grew wealthier as gold and silver entered the

country from trade and piracy. A price revolution that first hit Spain as

riches flowed in from the New World now caught up with England as costs

increased fivefold during the century.

Wage laborers, farm hands, and other members of the lower

echelons, however, became worse off as wage increases failed to keep up with

the rising cost of living, and real earnings declined. In today’s parlance,

inflation was rampant, and people on fixed incomes or set wages suffered. Even

an impecunious nobleman, whose livelihood depended on fixed rents, might find

himself hard-pressed and have to sell off some property. By the end of the

century, in poor, remote parts of the country, many people living on starvation

wages died from hunger.