Daily Life During The Reformation (27 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

In Scotland, music was becoming popular in the homes by the

beginning of the sixteenth century; the harp, fiddle, lute, spinet, and various

other instruments were all used domestically. Groups of musical people sprung

up, especially in the towns, where both players and singers enjoyed getting

together.

The Swiss, Felix Platter, studied the lute when he was

eight years old. When other boys also learned to play the instrument, they

formed a sort of musical circle. Although in other parts of Europe the lute was

considered an instrument of the court until the seventeenth century, it was

pervasive among the middle and lower-middle classes of Switzerland. Also

popular at this time were the clavichord, harp, viola, Jew’s harp, dulcimer,

and spinet.

Religious Music

Unlike some religious fanatics, Luther viewed music with

high esteem. He himself was an accomplished musician and composed hymns. He

further believed that music should be taught in schools as part of the training

of young men entering the priesthood. He advocated that common people needed to

hear the Word of God and to sing His praises in their own languages not, as

before the Reformation, only in Latin as it was sung by church choirs. German

pastors writing hymns based on the psalms were advised by Luther to use the

most simple, common words but keeping to the meaning of the psalms as closely

as possible. In Protestant churches, Luther dispensed with the choir and

allocated singing to the congregation. Johann Sebastian Bach, a Lutheran,

taught his students that music was an act of worship. He said all musicians

should commit their talents to the Lord Jesus Christ.

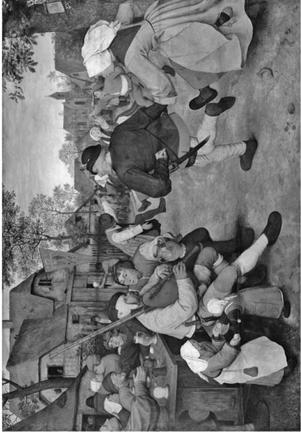

Peasant Dance. Pieter Brueghel

the Elder, 1568. A festive scene of peasants dancing, drinking, and eating. The

painting depicts a couple kissing, a young girl being pulled to join in the

dancing, and children imitating the adults.

David Teniers, 1633. Music in

the kitchen.

ART AND THE REFORMATION

Religious art thrived throughout the middle ages, and the

popes were often its patrons. Papal support continued in Catholic countries

after the Reformation. Protestant countries, on the other hand, did not

construct large cathedral buildings for their simplified religious activities.

They denounced ecclesiastical painting and sculpture and shunned religious

trappings.

The Reformation initiated a new tradition that redirected

artistic efforts into secular forms such as landscape and portrait painting.

Religious art continued much longer in Catholic countries. Iconic images of

Christ, the Virgin, the saints, and scenes from the Passion as subject matter

became less frequent as biblical portrayals of contemporary life with moral

overtones became preferred subjects. Some works displayed sinners accepted by

Christ, in sympathy with the Protestant orientation that salvation comes only

through God’s grace.

The Reformation prompted a surge of iconoclasm since many

Protestant sects regarded religious paintings and sculpture as idolatrous.

Zwingli and Calvin took all religious images from the churches, while Luther

permitted them to remain as long as the congregation was made to understand

that such imagery was simply symbolic and of little significance.

Since one of the principal theological differences between

Protestantism and Catholicism concerned transubstantiation (or literal

transformation of the Communion wafer and wine into the body and blood of

Christ); Protestant churches often selected altar piece scenes portraying the

last supper, a reminder to the congregation of the purely symbolic message of

the Eucharist. Catholics, wishing to stress the actual transformation of the

bread and wine into the body of Christ preferred to see crucifixion scenes

above the altar.

Perhaps more than Catholics, Protestants took advantage of

printmaking in northern Europe to mass produce visual images of religious

opponents and their beliefs in the form of caricatures that were often violent,

vulgar, and defamatory.

Among Protestants, portraits of reformers were in demand;

and their likenesses were sometimes painted into biblical scenes. After the

first years of the Reformation, however, Northern European artists concentrated

less and less on religious art.

The great genre painter of his time, Pieter Brueghel of

Flanders, was employed by both Catholic and Protestant patrons. He devoted much

of his paintings to landscape and to sixteenth-century peasant life in

Flanders. His

Wedding Feast

, depicting a peasant wedding dinner held in

a barn, does not refer in any way to events of religious, historical, or

classical import. Brueghel’s work gave impetus to many future northern

landscape artists who painted in a similar genre.

In Catholic Italy, the painting of the Last Judgment by

Michelangelo in the Sistine Chapel came under attack during the

Counter-Reformation for nudity, for a depiction of a clean-shaven Christ

standing, and for including the pagan figure of Charon.

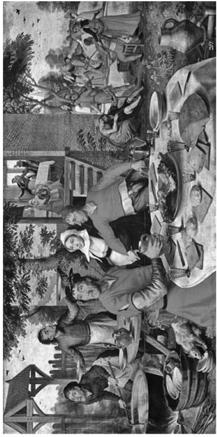

Peasant Feast by Pieter Aertsen,

1550.

THE COUNTER-REFORMATION AND ART

Protestants, in recognizing that the division between

sacred and secular was artificial, felt they could approach God directly

without the use of intermediaries; Catholics, on the other hand, maintained the

tradition of separation, seeing a need for intermediaries. In so doing, they

showed reverence to images. The art produced at this time by each side focused

on such differences, especially in the case of artists in Catholic countries

who were forced by the Church to adhere to the medieval tradition of turning

out only paintings with religious themes. Artists in Protestant countries, by

contrast, generally painted ordinary people. Subject matter thus provided the

main distinction between Reformation and Counter-Reformation art.

At the time, portrait painting became popular in northern

Europe; and Protestant works showed more realism. In the south, during the

Counter-Reformation, artists were still bound to the glorification of Catholic

traditions, graphically portraying immaculate-looking saints undergoing

martyrdom or Christ and the Virgin Mary.

To encourage piety, decrees emanating from the Council of

Trent demanded that art provide an accurate account of a biblical story or the

life of a saint. In 1563, the Council instructed that paintings should not

include anything profane or lustful and could not be placed in churches unless

approved by the bishop.

The reforms resulting from the Council set the tone for the

Counter-Reformation, and pictures of Christ were now promoted that only showed

Mary on bended knee before her child. She no longer was permitted to be shown

swooning at the foot of the cross; in scenes of the last judgment she had to be

portrayed sternly sitting beside Christ. There was no room for artistic

imagination.

The Venetian artist Paolo Veronese was summoned by the

Inquisition to explain why his Last Supper, a huge canvas designated for the

refectory of a monastery, contained, according to the inquisitors, “buffoons,

drunken Germans, dwarfs and other such scurrilities” as well as extravagant

costumes and settings. Veronese was ordered to change his painting within three

months. He only changed the title to

The Feast in the House of Levi

, still an event from the

Gospels but less central to doctrine, and the matter was closed.

As the Counter-Reformation progressed in strength, the

Catholic Church grew more confident; and Rome again asserted its universality

in nations around the world. The Jesuits spread the “true” faith sending

missionaries to Asia, the New World, and Africa and made use of the arts to

spread their message, all of which had a profound impact.

In producing secular art, the Reformation artists glorified

God by portraying the natural beauty of His creation. Catholics of the

Counter-Reformation did not share this view, believing that art must have a

didactic religious content.

12 - CLOTHING AND FASHION

Wherever

the Reformation became entrenched, fashions changed, often reflecting the

Protestant ethic with less flamboyant styles than those worn in the Renaissance.

At the same time, while the Catholics stressed imagery and ceremony, the

Protestant view was that faith should be expressed privately with more emphasis

on the spiritual than the material.

Class differences were primarily shown by the style and

quality of fabric, and the influx into the towns of a large variety of people

from other lands and different levels of society permitted the citizenry to

evaluate and judge one another’s relative wealth and status as reflected in

their dress.

Poor people throughout Europe wore clothes of coarse cloth,

and this did not change much during the century. But fashion for those who were

better off was very diverse. The dramatist, Thomas Dekker, reflected on the

clothes worn by friends:

‘his Codpeece is in Denmarke,

the collar, his Duble

and the belly in France, the

wing and narrow sleeve

in Italy: the short waste hangs

over a Dutch Botchers

stall in Utrich: his huge

Sloppes speakes Spanish:

Polonia give him the Bootes.’

SPAIN

In the middle of the sixteenth century, many western

European countries, both Protestant and Catholic, adopted the styles of the

Spanish nobility. The cut of the clothes and their rigid and formal elegance,

along with perfect distinction of line caught the attention of everyone

interested in fastidious dressing. Red, green, and yellow were popular colors,

although the symbol of the elegance of Spain was always black. Italy and

France, in particular, took on the predilection for black.

Women

Spaniards believed woman was the instrument for seduction,

and that besides her face, the principal symbols of temptation and sin were the

signals of her fertility, her hips and breasts. These were kept well covered,

although the face remained exposed. Skirts fell right to the ground and shoes,

made of wood or cork with high soles, were worn, so the skirts would not drag

in the dirt.