Daily Life During The Reformation (8 page)

Read Daily Life During The Reformation Online

Authors: James M. Anderson

Abuses arose in the way many ecclesiastical benefices were

conferred often for the personal interests of the petitioner rather than the

spiritual needs of the faithful. The lives of the higher ecclesiastics in Rome,

in tune with the Humanist and Renaissance ideals, became more worldly than

spiritual, leading to a love of luxury and profligacy. Ignorance and lack of

training among the lower clergy left much to be desired.

Although the Church imposed clerical celibacy as a legal

principle, in practice it was often ignored. Clergymen kept mistresses who were

supported with Church funds, and male offspring of bishops or abbots (referred

to as nephews) often found lucrative positions in the Church, universities, or

the law. The female children (or nieces) might find themselves administering

convents or marrying members of the nobility.

In 1492, Rodrigo Borgia became pope under the name of

Alexander VI. His immoral way of life outraged many Christians. At his

coronation he appointed his 18-year-old son, Caesare, to the Archbishopric of

Valencia; however, Caesare neither went to Spain nor took religious orders. The

pope’s daughter, Lucrezia, married three times, had children with other lovers,

and was the subject of much scandal. Tales of wild orgies at the Vatican were

rampant, but anyone who denounced such abuses could be excommunicated or worse.

Free preaching was prohibited, and all papers and books that were tainted with

the ideas of previous reformers such as Wycliffe or Hus were burned.

A boy could become a bishop, a profitable position, if his

father paid the price. Then there were dispensations or exemption from normal

Church laws and practices available to those who could afford them.

The sale of sacred relics believed to have the power to

heal and bring good fortune was another matter of contention. For some

skeptics, this was pure superstition, of no value, and most often, a swindle. A

splinter of the true cross, a tooth, or a piece of bone of a saint, some object

said to have been once used by the Virgin Mary or by Christ Himself—all were

peddled throughout Europe.

Among the uneducated, village priests were generally

treated with respect. They gave counseling and advice in matters both in and

outside a religious context and were usually available to assist with family

problems.

But priests were not always in favor with their

parishioners. In 1524, the parish of Saint Michael in Worms deposed its priest,

Johann Leininger, who then made an official complaint. The matter was taken up

by the town council, and church wardens and parishioners were asked to explain

their actions. They had often complained, they said, of the scandalous life of

the priest who lived in sin with a woman and had sired a child. In addition,

the woman had taken on the position of sexton. Leininger was also accused of

misusing church funds: an expensive green cloth had been bought to make Mass

vestments, but the priest had used it to have a coat made for his son. He had

also misspent 10 gulden belonging to the church and then given his parish

registers to the dean of the cathedral, although they were under the control of

the church wardens. Finally, he had refused to administer the sacraments to a

gravely ill woman until he was first paid the Mass penny.

While Spain, England, and France had usurped the right of

the pope to appoint bishops and other high clergy in their realms, people of

the Holy Roman Empire, especially the secular rulers, resented the pallium, the

large tax payable to Rome for the investiture or change in the diocese of an

archbishop, bishop, or abbot. The tax had to be raised by the inhabitants. In

addition, the entire income of the first year after the investiture (

annates

)

accrued to the papal treasury. This constituted a continuous drain on the local

economy. Added to these onerous costs were the journeys to Rome, where prelates

during their residence held court in a style of sumptuous magnificence, all

paid for by the parishioners.

It was to the benefit of the Church to maintain an

ignorant, illiterate, and unenlightened peasantry. Even people who could read

Latin were not allowed to read the Bible. Possession of it was a criminal

offense and could result in the execution of the accused. Sometimes translators

and publishers were burned along with their work.

The Catholic Church could use the scriptures selectively.

The peasant population remained in perpetual fear of hell’s fires, making it

easier to extract their last pennies. Moreover, the sale of indulgences for

remission of sins committed up to the time of purchase was now being practiced

as never before with a view to meeting the increased expenditure of the

Vatican. Even the monk, Martin Luther, asked why people should pay for a church

so far away and one they would never see.

The unifying cultural foundation of Europe for well over a

thousand years, the Roman Catholic Church, was complacent in its power and

failed to recognize the coming maelstrom that would engulf the continent. Careful

inquiry into the scriptures and a desire among some Catholic scholars to return

to the earliest and basic principles of Christianity were ignored until it was

too late.

4 - WITCHES, MAGIC, AND SUPERSTITION

Since

remote times, witches, village healers, and spell-makers in Europe had been

both respected and feared because of their powers to bring forth good or evil,

health or death. By the sixteenth century this had not changed. Much of western

Europe engaged in massive witch hunts from about 1550 to about 1680 when an

estimated 100,000 villagers were sentenced to death for sorcery, the vast

majority either spinsters or widows.

Those suspected represented a threat to Church authority,

accused of being in league with the devil and casting spells. The penalty for

witchcraft was death by strangulation, drowning, public burning, or

decapitation.

It was widely believed that the condemned had an intimate

knowledge of the use of herbs and other ingredients to concoct potions, which

could both cure diseases or cause harm to recipients. Rituals, magic words,

snakes, and lizards were often part of their ceremonies. They could prevent

storms and make crops grow, and if malevolent, they could ruin a crop, family,

or individual.

A common type of sorcery, sympathetic magic, involved a

piece of clothing, jewelry, or a lock of hair that belonged to the person on

whom an evil spell was to be cast. The victim who strongly believed he or she

would sicken and die, sometimes did.

It was also thought that witches could fly, breaking away

from earthly constraints to travel in the spiritual world, riding on demons

accompanied by crows and ravens. They could also change their shape and become

goats, cows, or other animals, making it difficult for witch hunters to find

them.

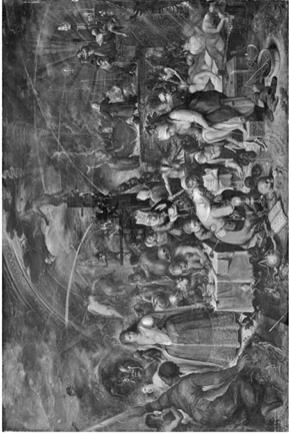

A depiction of a witches’

sabbath, by Frans Francken the Younger, 1607. This early seventeenth-century

painting shows some of the alleged practices of witches, including flying on

brooms, murder, spells, and bubbling cauldrons.

AGENTS OF THE DEVIL

A prominent charge was that witches participated in

activities known as the Witches’ Sabbat. According to the Church, such

festivals were secret and involved obscene rites with the devil. Alleged

witches often confessed under prolonged torture that they had been to Sabbats

where they pledged service to Satan and admitted that Sabbat ceremonies began

with new initiates having sex with the devil or his demons. Initiation

ceremonies might also include sacrificing an animal or child. The torturers

were eager to hear such stories, and the victim, preferring death to gruesome

prolonged agony (that would continue until the desired outcome), was ready to

confess to anything.

Christians believed that Satan was able to counter some of

God’s designs and saw this as an apocalyptic struggle between good and evil in

which no one was certain whether events happened because of divine or evil

influence. It was impossible to determine how much of human conduct was based

on individual freedom, how much determined by God, angels, stars, fortune, or

luck, and how much was regulated by profane intervention. The question that

always arose in learned circles was how these forces could be influenced in

such a way that one could avoid misfortune while fulfilling God’s laws and gain

eternal life.

In 1568, Jean Weir, a physician, spoke of the existence of

72 princes of the underworld, and over seven million infernal spirits formed

into 111 legions each with 6,666 fiends. Others proclaimed more than one

billion demons organized into legions, cohorts, and companies, each containing

over six million individuals.

It was believed there were demons confined to the air

responsible for storms and lightning and others to the ground living in

forests. Still others were in the sea (female devils), but all had one

purpose—to torment man. These kinds of stories were believed not only by the

average person but also by the elite and by educated priests. People were

frightened by the different forms, human and animal or even vapor and

invisibility, which devils could take to conceal their presence. Theologians of

the time attached great importance to the incube (male demon) and succube

(female demon) who could invade and possess the human body. In such cases, they

would call for the victim to undergo exorcism.

PROTECTION FROM EVIL

Evil was everywhere and had to be countered by any and all

means authorized by the Church. Talismen such as trinkets or candles, blessed

by a priest, would ward off evil spirits. On the day of the Feast of the

Purification of the Virgin, candles of all sizes were brought to the church to

be blessed. Large ones were brought by heads of households, slim, tapered ones

by women and girls, and penny candles by boys. They were piled up in baskets

before the altar and after being blessed, were taken home and used in family

devotions. The large house candle symbolizing Christ was lit by the death-bed

or carried along behind the bier in funeral processions. It was also lit during

bad weather to ward off crop-damaging hail, storms, or malevolent spirits. The

tapered candles of the women were lit during childbirth and placed by the hands

and feet of the mother to discourage the presence of malignant spirits. Penny

candles were lit on All-Souls Day and Advent for family devotions.

Holy water, blessed by a priest, had similar properties to

charms and candles as protection against evil forces that caused hail,

lightning, thunder, and severe storms. The Augsburg ritual book relates that

whoever was touched or sprinkled by the water would be free from all

uncleanness and all attacks of evil spirits. Further, all places where it was

sprinkled would be preserved free from harm, and no pestilent spirits would

reside there. Holy water could heal sickness, shield domestic animals from wolves,

and protect plants and seedlings over which it was distributed. It had

beneficial power over homes, food, herbs, grain and threshing floors, and much

more.

In Paris there were some fifty religious buildings in the

Ile

de la Cite´

alone, many of which had been built to commemorate a saint.

Saints played a large role as everyone looked first to them to cure illnesses,

insure a good harvest or safe childbirth, as well as stave off evil spells and

malevolent spirits.

Each saint was assigned certain responsibilities, and everyone

knew which one to appeal to for which ailments, which pilgrimages to undertake

to benefit their well being, and who would take care of them and watch over

them as they traveled. A great number of saints’ relics, some in the form of

powder or potions, were carried. Servants often kept a piece of bread in their

pocket, blessed by a priest, to protect them, prevent them from contracting

rabies, and to kill rats. Many people believed that the end of the world was

imminent, but meanwhile, God was keeping His eye on them. His pleasure was

manifested when the harvest was good; His ire when it was bad.

CROWS, RAVENS, AND CATS

Crows and ravens were both despised and revered. It was

forbidden in England to kill either of them. It was possible to incur a large

fine for harming ravens for if they did not consume carrion, the putrified

flesh would poison the air.