Daily Life In Colonial Latin America (15 page)

Read Daily Life In Colonial Latin America Online

Authors: Ann Jefferson

Enslaved laborers on the plantations of Brazil lived in

small one-room huts no different from those of the rural working people of

Spanish America, or in large structures divided into rooms with one family

occupying each room. In Brazil, it was common for working families, whether

made up of slaves or freemen, to be allotted a garden plot to grow at least

some of their own food. Indeed, this arrangement was not only a regular but

often an essential feature of plantation life owing to the notorious failure of

many sugar planters to provide adequate nourishment to their slaves. A 1701

decree by King Pedro II of Portugal reflects this fact. In it he ordered his

officials in Brazil to force local slave-owners “either to give their slaves

the required sustenance, or a free day in the [work] week so that they can

themselves cultivate the ground.” At times, these small-scale cultivators

might sell their surplus to the

casa grande

(main house) in exchange for

a little money they could save toward the purchase of their freedom or spend on

a small luxury.

Circumstances were similar on large sugar plantations in

Spanish America. One such property, located just south of what is now Guatemala

City and home to some 200 enslaved residents in 1630, was described by an

English observer as “a little Town by it selfe for the many cottages and

thatched houses of

Blackmore

slaves which belong unto it.” As in

Brazil, the houses of the working people of Spanish America, both slave and

free, often included a garden plot as well.

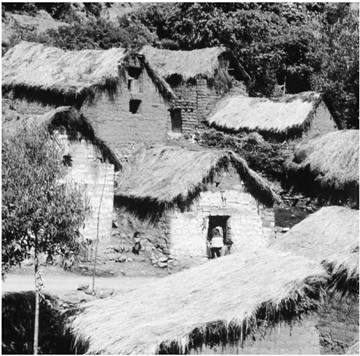

Homes

constructed of adobe and thatch in modern Ecuador, a style of housing that has

been in use in some areas of Latin America for hundreds of years.

Urban Housing

People who left rural areas to move to a nearby town or

city sometimes lived where they worked, in the homes of the wealthy. These

domestic workers had a small space in the home of their employer, an

arrangement that afforded protection from the precariousness of independent

life, if not from members of the family they served. In exchange for this

security, they had to be available for work as needed, meaning at any hour of

the day or night. For those who did not find a place with a wealthier family

the housing prospects were grim. Many recent arrivals found, or helped

themselves to, some kind of material with which to construct a makeshift

shelter, designed to serve as a temporary home, although frequently what was

conceived as temporary became permanent or lasted at least until the next

earthquake or mudslide destroyed it. These little dwellings clustered together,

completely devoid of any formal plan, in a ravine or other area marginal to the

city proper, gradually forming whole neighborhoods of slums that housed much of

the working population of the city.

Priests lived in housing supplied by the church, although

if they came from wealthy families, they might live in lavishly appointed homes

in town or sometimes on a hacienda they had bought with family money; the

servants of priests were usually Indians or

casta

members of the working

classes. Secular urban professionals like lawyers, doctors, merchants,

tradesmen, or shopkeepers and officers in the military lived in homes that were

more or less well appointed, depending on their income.

The wealthy generally lived in town. In Brazil, plantation

owners and their families might live in the countryside on their sugar

plantation, or

engenho,

although they would usually have a home in the

nearest city as well, and family members moved back and forth. The homes of

government functionaries, most of them sent to the colonies directly from

Europe as agents of the crown, and of the wealthiest colonists in both Spanish

America and Brazil displayed art objects and treasures imported from the mother

country. Things produced in the colonies could not compete in beauty or value

with the luxury goods, possibly originating in China or India, brought over

from Europe.

Architecture and Social Relationships

In the countryside, even the homes of the wealthiest owners

of large estates were often like large fortresses of many rooms with almost no

furniture. For the most part, the building materials were the same as those

used in more humble dwellings with the exception of the roof, which would often

be of tile rather than thatch. Some adornments might be added, including walls

of stucco with wooden beams and interior wood paneling. Rooms, usually without

windows, were arranged around a central patio, a style based on the houses of

the ancient Romans that were built around an open-air space known as the

atrium. Fancy houses in town might be constructed in a figure eight around two

patios, a front one with a formal garden and possibly a fountain, and a

functional back patio with an open water storage tank for washing the laundry

and watering the horses, and with a kitchen and food storage area off to one

side.

Architectural styles were also affected by the quite

practical consideration of earthquakes. As a result, houses of the wealthy,

especially in the Andes, were sometimes constructed for flexibility with beams

linked by heavy leather bindings in place of nails. In areas of frequent

tremors, wide sturdy archways might be included to provide protection for the

family members.

Compared with the housing of today’s industrialized world,

the houses of people in colonial Latin America provided precious little

comfort. Most large houses were drafty and dark; most small houses were cramped

and cheerless. Furniture, what there was of it, was built for function rather

than comfort. This generalized lack of comfort at home reflects an important

aspect of life in the colonial period, however, which is that people spent a

lot more time outside in public spaces. A great deal of work was done outside,

either in the fields or in the streets and open-air markets. Going to the local

spring or well for water, or going to wash the laundry at a local stream or

public wash house became an opportunity to chat with others, exchange news and

gossip, and spend parts of the day outside the house. This was more true for

the working people than for their social “betters,” however. Women from elite

families were expected to stay at home unless they were heading out to church,

usually in a group of other women from the household. If the family could

afford a carriage, the women would make use of it to avoid the streets, which

were sometimes filthy and, depending on whether it was the dry or rainy season,

were likely to be a dustbowl or a sea of mud.

Another interesting feature of housing in the colonial

period is that it was more crowded than the houses many people are used to in

today’s world. The homes of the wealthy included the patriarchal family and

might also house maiden aunts, a widowed mother, or a ne’er-do-well brother; a

quantity of domestic servants, free or enslaved, commensurate with the family’s

wealth; possibly one or more illegitimate children of a family member; and the

occasional visitor. The families of poorer people may have lacked this wide

variety, but their homes were smaller and often did contain an extra member or

two, possibly a farmworker, a “girl” to help with the housework, a widowed

mother, or an unwed sister or aunt. To some extent, family members were driven

out into public space because there were so many people in the house.

CLOTHING

In colonial Latin America, clothing truly did “make the

man,” as the saying goes. There was no greater marker of social class than

clothing. A humble home is left behind when one goes out into the public arena,

but a person’s dress conveys his rank in society. The more European the style

of one’s clothing, the more respect he commanded. Even wealthy people had fewer

clothes than modern industrial production provides many people of today’s

world, but the clothing they did have was designed to communicate their social

standing. People dressed in the most elegant style they could afford in their

attempt to assure their position in high society. Clothing represented a

necessary investment in social standing.

Elite Clothing Styles

Elites or people aspiring to elite status adopted European

clothing, meaning, for men, leather shoes or boots, silk hosiery, silk or linen

underwear, knee breeches or other pants imitating the latest European fashion,

a jacket and shirt with sleeves, an overcoat, and a hat of felted wool. Women

of high society possessed different clothes for different activities, outfits

for riding and going to church, as well as everyday dresses, party clothes, and

various capes, shawls, and lace head coverings. They favored silk underwear and

nightgowns; many petticoats; long-sleeved, ankle-length dresses, possibly of

Asian silk trimmed with lace; and footwear of fine leather.

Clothing Styles among the Common People

The common people dressed in practical clothing of home

manufacture, constructed of local materials, especially cotton or at times wool

from the sheep brought by the Spanish in the 16th century. The working men of

New Spain generally wore durable cotton fashioned into loose-fitting pants and

shirt. In addition, they frequently wore some kind of handwoven cloak that

replaced the overcoat of their social “betters.” Many people went barefoot, but

they might have had a pair of sandals made of hides. On their heads, they often

wore a straw hat with a wide brim for protection from sun and rain. In colder

areas like the Andean highlands, men wore more wool and a hat made of some

fiber. Since the clothing of working people was usually made of local materials

and had to suit local weather conditions, areas based on a cattle economy

tended toward leather clothing, while cotton was preferred in warmer areas, and

wool in the chilly highlands.

Women wore homespun cotton or wool skirts, sometimes

covering several petticoats, and over their blouse, or

huipil,

they

threw a shawl of cotton or wool that doubled as a carrier for the latest baby

or for goods on their way to or from market. Underwear was nonexistent for both

men and women of the working classes.

Most enslaved workers, especially those employed in

plantation labor, were not in a position to buy their clothes; they wore what

was provided for them. While conditions varied somewhat from one work site to

another, the general rule was for owners to spend the absolute minimum to

clothe the workforce. They might allot each worker a few yards of the cheapest

cloth to fashion into pants or a skirt. Sometimes the workers would receive a

new item of simple cotton clothing once a year or every other year. In very hot

conditions like the sugar-boiling house, the workers might go naked or nearly

so. Some contemporary accounts relate that the slaves went naked, but most

drawings show them with pants or a skirt of handwoven cotton cloth.

Enslaved workers who earned wages, paying their owner his

share and keeping a share themselves, sometimes invested that money in items of

clothing or jewelry for use on festival days. Foreign observers often remarked

on the strikingly elegant clothing worn by some women of color, including

slaves, in Mexico City, Lima, and other urban areas. This phenomenon was

widespread enough to prompt a number of apparently ineffectual royal decrees

prohibiting such displays of finery by anyone outside the colonial elite. In

some cases, it was status-conscious slave owners who purchased the

“extravagant” clothing worn by women (or men) who served them, although

considerations of status were no less important when an enslaved person

acquired a fine article of clothing on her own. Public display of the article

served to establish its wearer’s claim to the upper rungs of the social

hierarchy, in this case the slave hierarchy.