Daily Life in Elizabethan England (39 page)

Read Daily Life in Elizabethan England Online

Authors: Jeffrey L. Forgeng

Entertainments 195

Tennis. [Allemagne]

the upper classes, and it was only played by men. The plebeian version was handball: as the name suggests, the ball was hit with the hands rather than with a racket. A similar game was shuttlecock, comparable to modern badminton. The shuttlecock was a cylinder of cork rounded at one end with feathers stuck in it; it was batted back and forth with wooden paddles known as

battledores.

A less demanding outdoor game was bowls, similar to the modern

En glish game of that name, or to Italian

bocce.

Each player threw two balls at a target, trying to get them as close as possible once all the balls had been thrown. Bowls was so popular that there were commercial bowling alleys, and the game could be quite sophisticated, involving various shapes of balls, an elaborate terminology for describing the lay of the ground and the course of the ball, and a formalized system of betting. Moralists often criticized the game, yet when betting was not involved it was played by even the most respectable men and women.

A slightly more dangerous variant was quoits, in which a stake or spike was driven into the ground and players tossed stones or heavy metal disks at it. The game seems to have been played with vigor rather than finesse, and serious injury was known to result. The modern game of horseshoes is a variant of quoits.

196

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Another game in the same family was Penny Prick. In Penny Prick, a peg was set in the ground with a penny on top; players would throw their knives at it, trying either to knock the penny off or to lodge their knife in the ground closest to the peg. A very simple game in this class, played by children, was Cherry Stone, in which the contestants tried to throw cherry pits into a small hole in the ground.

Similar to modern American bowling was the game known by such

names as nine-pegs, tenpins, skittle pins, skittles, or kittles. Nine conical pins were set up on the ground, and players would try to knock them down with a wooden ball. In a related game called kayles or loggats, the pins were knocked down with a stick instead of a ball. Country folk sometimes used the leg bones of oxen for pins.

Some games involved a great deal of running and little or no equipment. The game known in modern schoolyards as Prisoner’s Base was

played under the name Base or Prison Bars. A particular favorite in this period was Barley Break, a chasing game in which two mixed-sex couples tried to avoid being caught by a third couple, with the couples changing partners each time. The game, with its grabbing and constant changing of partners, was proverbially an opportunity for rustic flirtation.

Other athletic sports included footraces, swimming, and tug-of-war (probably known by multiple names—the attested version was called

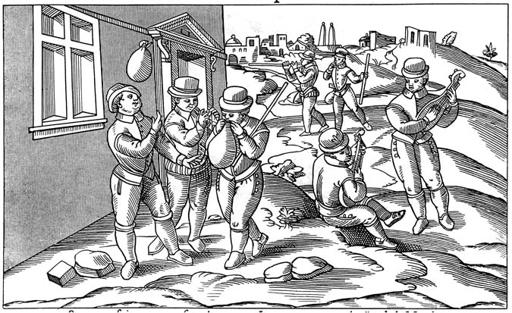

Sun-and-Moon). Men threw spears, heavy stones, or iron bars, and they competed at jumping for distance or height, sometimes with a pole. Vaulting, a sport once practiced by knights as a way to develop strength and Playing with inflated bladders. [Allemagne]

Entertainments 197

skill as horsemen, still had some currency, and the vaulting-horse was still made to resemble an actual animal. People also liked simply to ride or take walks for exercise; members of the upper classes were especially fond of strolling in their gardens after a meal.

A variety of parlor-games were played by children, merrymakers at

times like Christmas, and flirtatious young men and women. In Hot Cockles one player hid his head in another’s lap while the others slapped him on the rear—if he could guess who had slapped him last, the two traded places. Blindman’s Buff, also known as Hoodman Blind, was a similar game in which a blinded player tried to catch the others while they dealt him

buffs

(blows). If he could identify the person he caught, they would trade places.

TABLE GAMES

Many games were purely for indoor recreation. Among table games,

chess was the most prestigious. Its rules were essentially the same as they are today. Chess was unusual among table games in that it did not normally involve betting. For those who wanted a simpler game, the chess board could be combined with

table men

(backgammon pieces) for the game of draughts (now known in North America as checkers), again with essentially the same rules as today.6

Fox and Geese and Nine Men’s Morris were two simple board games

in which each player moved pieces about on a geometric board, trying to capture or pin his opponent’s pieces. Boards for these games could be made by cutting lines into a wooden surface or by writing on it with chalk or charcoal. A simpler relative was Three-Men’s Morris, played on a three-by-three unit board with three men on a side—the progenitor of Tic-Tac-Toe, but allowing the pieces to be moved once they were placed.

There were several games in the family known as Tables, played with the equipment used in modern backgammon. Backgammon itself was not invented until the early 17th century, but the game of Irish was almost identical to it, although without the rules applying to doubles on the dice, which made it slower. Games at Tables varied enormously. The childish game of Doublets involved only one side of the board: each player stacked his pieces on the points of their side, then rolled dice first to unstack them, then to bear them off the board. Perhaps the most complex game was Ticktack, in which the general idea was to move all one’s pieces from one end of the board to the other, with several alternative ways of winning the game at single or double stakes en route.

Dice were the classic pastime of the lower orders of society—they were cheap, highly portable, and very effective at whiling away idle time (for which reason they were especially favored by soldiers). Dice games were played by the aristocracy as well; Elizabeth herself was known to indulge in them. The dice were typically made of bone, and the spots were called

198

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

the

ace, deuce, tray, cater, sink,

and

sise

—thus a roll of 6 and 1 was called

sise-ace.

The classic dice game was Hazard, a relative of modern Craps.

Cards were widely popular throughout society, and inexpensive block-printed decks were readily available. Elizabethan playing cards were unwaxed, and the custom had not yet evolved of printing a pattern on the back to prevent marking. For this reason, it was customary to retire the deck every Christmas—the old cards often being recycled as matches.

Playing cards were divided according to the French system, essentially the same one used in English-speaking countries today. The French suits were the same as in a modern deck, and each suit contained the same range of cards. The first three were called the Ace, Deuce, and Trey, and the face cards were called King, Queen, and Knave (there was no Joker).

The cards had only images on them, no letters or numbers. The images on the face cards were similar to modern ones, save that they were full-body portraits (unlike the mirror-image on modern cards).

Many Elizabethan card games have disappeared from use, but some

still have modern derivatives. One and Thirty was similar to the modern Twenty-One, except that it was played to a higher number. Noddy was an earlier variant of Cribbage (which first appeared in the early 17th century). Ruff and Trump were ancestors of modern Whist, and Primero was an early version of Poker.

POPULAR GAMES AND SPORTS, 1600

Man, I dare challenge thee to throw the sledge [hammer],

To jump or leap over a ditch or hedge,

To wrestle, play at stoolball, or to run,

To pitch the bar, or to shoot off a gun,

To play at loggats, nineholes or tenpins,

At Ticktack, Irish, Noddy, Maw and Ruff,

At hot-cockles, leapfrog, or blindman-buff,

To drink half-pots or deal at the whole can;

To play at base, or pen-and-inkhorn Sir John,

To dance the Morris, play at barley-break,

At all exploits a man can think or speak;

At shove-groat, venter-point or cross and pile,

At “Breshrew him that’s last at yonder stile,”

At leaping o’er a Midsummer bonfire

Or at the “Drawing Dun out of the mire.”

At any of these, or all these presently,

Wag but your finger, I am for you, I.

Samuel Rowlands,

The Letting of Humour’s Blood in the Head-Vein

(London: W. White, 1600), sig. D8v-E1r.

Entertainments 199

Shovelboard or shove-groat was an indoor game in which metal discs (which could be coins—

groat

was a name for a fourpenny piece) were pushed across a table to land as close as possible to the other end without falling off. A series of lines were drawn across the board, and points were scored according to where the piece stopped. Wealthy households sometimes had special tables built for this game. The simplest coin game was Cross and Pile, identical to Heads or Tails—the

cross

was the cross on the back of English coins, and the

pile

the face of the Queen on the front.

Another very simple game involved the tee-totum, a kind of top, used exactly like a Hanukkah dreidel. It had four sides, each bearing a letter:

T

for

take,

N

for

nothing,

P

for

put,

and

H

for

half.

Depending on which side came up, the player would take all the stakes out of the pot, get nothing, put another stake into the pot, or take out half the stakes.

A few new table games appeared during Elizabeth’s reign. Billiards appears to have been introduced from the Continent during this period.

The Game of Goose is first attested in England in 1597. This was the earliest ancestor of many of today’s commercial board games. Goose came as a commercially printed sheet bearing a track of squares spiraling toward the center. Players rolled dice to move their pieces along the track. Some of the squares bore special symbols: the player who landed on such a square might get an extra roll or be sent back a certain number of squares. The first player to reach the end won.

Some entertainments involved nothing more than words. Jokes were as popular then as now—there were even printed joke books. Riddles were another common form of word game. In general, Elizabethans greatly enjoyed conversation and were especially fond of sharing news: in a world without mass or electronic media, people were always eager for tidings of what was going on in the world around them.

PLAY AND SOCIETY

In a world where most people spent the bulk of their waking hours

earning a living, recreation played an especially important cultural role.

People’s work-time activities were heavily governed by practical factors, but their pastimes, unconstrained by the same material considerations, tell us much more about who they were and what they valued.

A person’s choice of pastimes said much about their cultural affiliations, rank, and gender. Tennis, hunting, and riding were pursued by the wealthy and fashionable. Football and wrestling were favored by country people and plebeian townsfolk. Archery was seen by some as old-fashioned, yet it had a strongly patriotic flavor, recalling the source of medieval England’s military might.

Women did not engage in martial, dangerous, or extremely vigorous

sports like fencing, football, or tennis. However, they might take part in lighter physical games such as Stoolball, Blindman’s Buff or Barley Break.

200

Daily Life in Elizabethan England

Games with minimal physical activity such as bowls and card games were especially common pastimes for women, and they often participated as spectators at sports that they did not play themselves, even violent sports like fencing or bearbaiting.