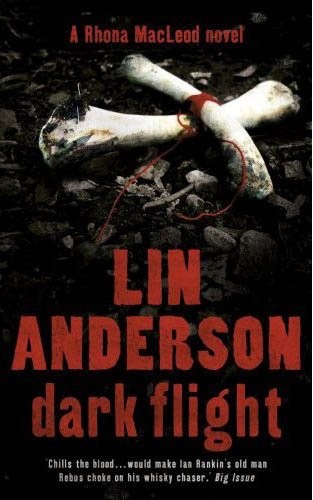

Dark Flight

Authors: Lin Anderson

Tags: #Fiction, #Crime, #Mystery & Detective, #General

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette UK Company

Copyright © Lin Anderson 2007

The right of Lin Anderson to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN:9781848945074

Book ISBN: 9780340922415

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

An Hachette UK Company

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

To Detective Inspector Bill Mitchell.

Dark Flight

The face that stared at him through the glass was his mum’s, but it didn’t look like her. Stephen’s mouth dropped open and real fear grabbed his stomach. His mum’s face was chalk white, her mouth twisted in pain. Behind her was a dark shadow.

Stephen dropped the bones.

Also by Lin Anderson:

Driftnet

Torch

Deadly Code

Thanks to Ted Coventry for his Nigerian input, and to Dr Jennifer Miller of GUARD for her help with bones and botanics.

SANNI DIVED LEFT

into thick undergrowth. The big four-by-four vehicle made a 180-degree turn, splattering red mud in a semicircle, and followed. Thorns tore at Sanni’s face and chest. He tasted blood. If he could only make the river. The rainy season had swollen it and the fast-moving water would carry him away from his pursuers. He smelt burning diesel as the vehicle stalled, its wheels churning the soggy clay. Sanni broke through the bushes that lined the river bank.

Rua

. Water.

Rua, da godiya

. Thank God. His small slight body stood, indecisive, on the high bank, as big black river ants ran up his thin legs, biting him savagely. Sensing someone behind, he sprang forward. But it was too late. His arm was gripped in a fist of steel. Sanni screamed, but there was no one to hear.

Monday

1

‘

YOU CAN GO

outside, but stay in the garden. Do you hear me, Stephen?’ His mum’s voice was shrill, like a witch’s.

Gran’s bedroom smelt of pee. His mum was stripping the bed, while his gran sat in a winged armchair, her hair a fluffy white halo. She winked at Stephen as he left the room. His gran was sick, but she wasn’t cross.

The garden was tiny and surrounded by a high hedge. Once, when he came on holiday, he’d helped his granddad cut the hedge, but now it was so tall it blocked the light.

Stephen stood on the closed gate, humming to himself . . . until he saw the bones.

They lay in the shape of a cross, on the pavement just outside the garden. Excitement beat the pulse at his temple. Already his active imagination was writing the bones into a story of pirates and treasure. He looked up and down the empty street. Whoever had dropped them was gone. Probably they would never come back. Conscience assuaged, Stephen dropped to his knees, slipped his small hand through the black bars and stretched his arm as far as he could. He grunted as

the metal dug painfully into his armpit, his face squashed sideways to the gate. Out of the corner of his eye he could see his fingers wriggling disappointingly short of the bones.

He withdrew his arm and rubbed it, muttering under his breath in a decisive manner, ‘I’ll have to go outside. I’ll just have to.’

He sneaked a look at the kitchen window. What if his mum was at the sink? His heart leapt. The window was blank. A mix of excitement and fear coursed through his veins and he swallowed hard.

He conjured up an image of his mum’s angry face if he disobeyed her and he wiped his mouth anxiously. She would go bananas, raving on at him about not doing what he was told. It was a scary thought.

But if he was quick? He saw himself zip out and in again almost instantaneously like Billy Whizz in the

Beano

comic. The bones were tantalisingly close. And it wasn’t really going outside, he told himself firmly. Not if he was

very very

quick.

Stephen slipped through, snatched up the bones and stepped swiftly back inside, pulling the gate quietly shut behind him. He stood stock-still, his heart thudding in his chest. At last he let his breath out in an exaggerated gasp. He had done it!

He smiled down at his prize.

The bones were about the size of his first finger, tied together with red thread. He held the cross to his nose and sniffed. They smelt like the garden when his granddad used to dig up the weeds.

He placed the bones in his left palm and ran his

finger over them, studying the three lines scored at the top of each one, which could be a magic mark.

A muffled voice made him look up guiltily. Had his mum seen him go out of the garden? He whistled through his teeth, and shuffled his feet, waiting for the shout that meant trouble.

But no shout came.

When he felt brave enough to look directly, the face that stared at him through the glass was his mum’s, but it didn’t look like her. Stephen’s mouth dropped open and real fear grabbed his stomach. His mum’s face was chalk white, her mouth twisted in pain. Behind her was a dark shadow.

Stephen dropped the bones.

‘Mum?’ His voice emerged in a whimper.

She opened her mouth as if to scream at him and he waited, rigid with apprehension. Then her face jerked towards the glass, once, twice, three times.

Stephen stood rooted to the spot, watching her neck whip backwards and forwards. Then it was over.

She caught his eye and held it. Her mouth moved in a silent exaggerated word.

RUN.

DR RHONA MACLEOD

ignored the metallic smell of blood mingled with stale urine, and raised her eyes to the ceiling, where cast-off bloodstains formed an arc.

Short heavy weapons tended to swing slowly and in short arcs. Judging by the spots on the ceiling, the instrument used to kill the old woman was probably long and light.

The body sat in an old-fashioned winged armchair, head slumped forward, fluffy white hair stained dark red. The skull gaped in a line from crown to neck. In the opening, contusions bunched like black grapes.

Larger drops splattered the slippered feet and surrounding beige carpet, their tail direction suggesting the victim was attacked from behind.

Rhona wondered if the woman had even realised her attacker was in the room. She secretly hoped she hadn’t. To die such a violent death was terrible. To anticipate it, even worse.

The hands that lay in the lap were small and pearly white, a threading of blue veins running like raised tributaries across the crêpy flesh. A worn gold wedding band hung loose on the fourth finger of the left hand, a delicate gold watch circling the thin wrist.

She wore a pale blue nightgown, a knitted shawl about her shoulders. Had it not been for the blood, it was as if she had fallen asleep in her chair and would waken with a crick in her neck.

The room had a threadbare quality, while retaining an aura of gentility, despite the gory contents. Every surface held an ornament, most of which looked like good china. There were three small, ornately framed paintings on the walls, dark oils of highland scenes.

The chair was placed so the woman could see the small television that sat on a chest nearby. A remote lay on the floor beside her, as though she had dropped it. To the left of the chair, the bed had its headboard against the back wall. The bed was newly made, crisp white sheets spoiled by crimson spray. On a bedside table sat a radio and three pill bottles.

Rhona lifted one with a gloved hand and read the label. Sleeping tablets. The other two might be medication for water retention and circulatory problems, but she would have to check. She bagged the bottles and labelled them.

It looked as though the old woman never left this room. And even here, she hadn’t been safe.

Detective Inspector Bill Wilson appeared in the doorway, his expression brightening at the sight of Rhona. ‘You got here fast.’

‘I was in the car when the call came through.’

Bill assumed an official air. In the midst of carnage it served as a survival mechanism. ‘The Procurator’s been. Decided he didn’t need to look in detail to give us the go-ahead. The duty pathologist pronounced

death, via a view from the window. He’ll wait until we ship them to the mortuary to take a closer look. McNab was keen to restrict access to the scene in case of contamination. Seems sensible.’

The name startled Rhona. She hadn’t realised DS McNab was back in town. ‘McNab’s the Crime Scene Manager?’ She tried to keep her tone light.

Bill gave a cursory nod. It was a name well known to both of them. ‘Want to take a look in the kitchen?’

The room gave onto a long narrow hall, which led to a back door. The layout was straightforward. A two room, kitchen and bathroom flat. The front room, normally a sitting room, had become Granny’s bedsit. According to the other SOCOs, the smaller bedroom at the back was filled with a three-piece suite circa nineteen fifties.

Aluminium tread plates had been laid throughout so no one would leave their own imprint on the scene. Unfortunately, whoever laid them had a longer stride than Rhona, and she had to jump from plate to plate. In other circumstances she might have laughed, but this blood bath held no place for humour.

A younger woman lay face down on the kitchen floor, her skirt pulled up to her waist. The blood had left her severed carotid artery in a series of spurts that corresponded to the beating of her heart. The arterial gush had hit the kitchen surface near the sink, leaving a large stain, several centimetres in diameter. Secondary splattering peppered the front of the kitchen unit.