Das Reich

For Anthea

who should have been here to read this

1 » 2nd SS Panzer Division: Montauban, Tarn-et-Garonne, May 1944

8 » ‘Panzer divisions are too good for this . . .’

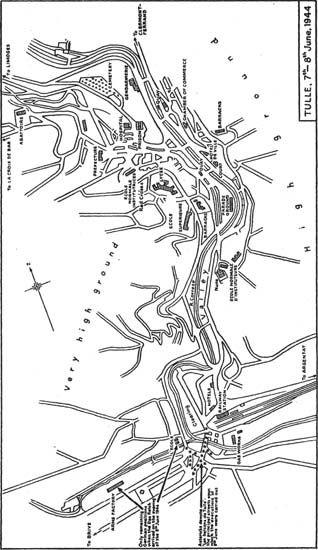

9 » ‘. . . a rapid and lasting clean-up . . .’: Oradour

Appendix A: 2nd SS Panzer Division’s memorandum on anti-guerilla operations, issued on 9 June 1944

Appendix B: Principal Weapons of the

maquis

and the 2nd SS Panzer Division

Bibliography and a Note on Sources

Illustration Acknowledgements

The author and publishers would like to thank all those who gave their kind permission to reproduce photographs here. Among others, we are grateful to Miss Vera Atkins, Mrs Pilar Starr, The Hamlyn Group, Askania Verlagsgesellschaft, HMSO, Editions Daniel & Cie, Verlag K. W. Schütz KG, SOGEDIL, Sygma, Popperfoto and Keystone Press.

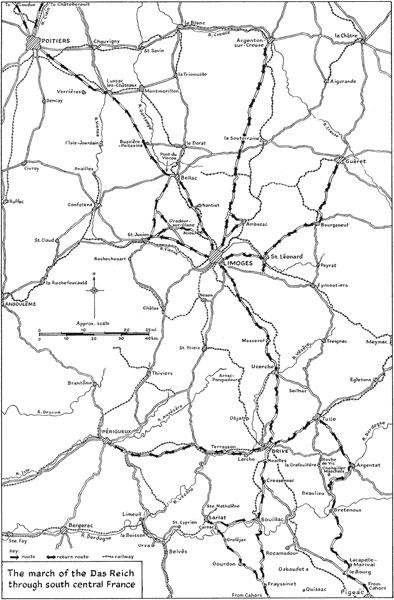

On 8 June 1944, some 15,000 men and 209 tanks and self-propelled guns of the Das Reich 2nd SS Panzer Division rolled out of Montauban in southern France, and began a march that ended 450 miles northwards in Normandy more than two weeks later. In the interval the division became one of the most dreadful legends in the history of France and World War II. This book is an attempt to tell its full story for the first time.

I have always been fascinated by the controversy surrounding guerillas, special forces, and their influence upon the main battlefield. I had initially considered writing a general study of the campaigns behind the lines in France, Yugoslavia, Italy and Russia, but the story of the Das Reich continued to nag me. I concluded that I could make a more original contribution to the subject of Resistance by examining this specific episode in some detail than by attempting yet another

tour d’horizon

. In his official history of the French Section of Special Operations Executive, Professor M. R. D. Foot wrote of the Das Reich story:

The extra fortnight’s delay imposed on what should have been a three-day journey may well have been of decisive importance for the successful securing of the Normandy bridgehead . . . Between them these [SOE] circuits left the Germans so thoroughly mauled that when they did eventually crawl into their lagers close to the fighting line . . . their fighting quality was much below what it had been when they started . . . The division might be compared to a cobra which had struck with its fangs at the head of a stick held out to tempt it: the amount of poison left in its bite was far less than it had been.

Here, then, was my starting point: a legend of guerilla action in World War II, the boldest of claims for an achievement by special forces. Pursuing the outline of the story further, it became even more fascinating, as I studied the involvement of the British and American Jedburgh teams in the attack on communications in the Das Reich’s area; the division’s capture of the British agent Violette Szabo; and the extraordinary history of some of the British and French agents most closely connected in building the Resistance groups that fought the SS.

During the months that followed, I interviewed men and women in England and America, France and Germany. It became evident that almost everything hitherto published was unreliable, and in many cases simply wrong. Accounts have been confused by the deliberate untruths of post-war German testimony in the shadow of war crimes trials, and by the fact that almost every Frenchman who fired upon a German in south-west France in June 1944 reported that he had been in action against the notorious Das Reich. Casualty figures were wildly mis-stated, and so were contemporary assessments of German plans and intentions.

I must now emphasize that the story I have written is neither full nor definitive – it could never be completely satisfactory in the absence of any but the sketchiest written records. So much has been lost with dead men, and so much forgotten with failing memories, that I have been unable to discover, for instance, which

maquis

group carried out every minor ambush, and which unit of the Das Reich returned its fire on every occasion. But I think that I have come as close to the reality as it is now possible to get.

My first source was the German war diaries and records of signal traffic in the Freiburg archives, which are an invaluable guide to what the Germans themselves believed that they were doing at the time. In the Public Record Office in London, I found the SAS files for 1944, and scores of fascinating papers on the debate in the Allied High Command before D-Day about what Resistance might and might not achieve. It is exasperating that so many relevant files – especially on war crimes investigations – are

still marked ‘Closed’ when there can no longer be any valid security pretext. The Paris library of the

Comité de l’histoire de la deuxième guerre mondiale

was especially useful for long-forgotten books published in the wake of the Liberation, and I received much help from the

Comité

’s local correspondents in southern and central France.

I leave readers to make their own moral judgments on the actions of the SS officers and men concerned in the story. I can only record my gratitude as an author that they met and corresponded with me at such length, above all Otto Weidinger and Heinrich Wulf. Albert Stuckler, former senior staff officer of the Das Reich, has compiled a vast file on its movements in 1944 for internal circulation among its veterans, which, like Colonel Weidinger’s regimental history of the Der Führer, entitled

Comrades to the End

, has been of immense value. As far as possible, I have tried to reflect the human emotions of the officers of the division in June 1944, divorcing my mind from the knowledge of the deeds with which they were associated. If I have been able to catch their mood with less fluency than that of the French and British, this may be because in my interviews with them, when certain questions had to be asked and answered, our conversations became stilted and distant.

The Veterans of the OSS in New York helped me to trace relevant survivors. I am deeply indebted to Captain John Tonkin and the other survivors of the ill-fated Bulbasket SAS mission who gave so much time and assistance.

Of the distinguished survivors of Special Operations Executive, a full list follows in the Acknowledgements, but I must especially mention Maurice Buckmaster, Vera Atkins, Selwyn Jepson, the later George Starr, Annette Cormeau, Jacques Poirier, Baron Philippe de Gunzbourg, and Mrs Judith Hiller, who lent me the fascinating and moving tapes and notes compiled by her husband, the late George Hiller, for a memoir he did not live to complete.

For this book, as for my earlier

Bomber Command

, Andrea Whittaker proved a brilliant German translator and interpreter.

Juliette Ellison gave me invaluable help interviewing former

résistants

– among whom I must single out M. René Jugie – in the hills of the Corrèze, the Dordogne and Haute Vienne through the long, wet June of 1980.

Above all, I must express my gratitude to Professor M. R. D. Foot, doyen of British and American historians of Resistance, former Intelligence Officer of the SAS Brigade in 1944, and one of the regiment’s few survivors of German captivity. He not only gave me hours of help and guidance as I researched this book, but later read the manuscript and provided scores of invaluable comments and corrections. None of this, of course, burdens him with responsibility for my errors or judgments.