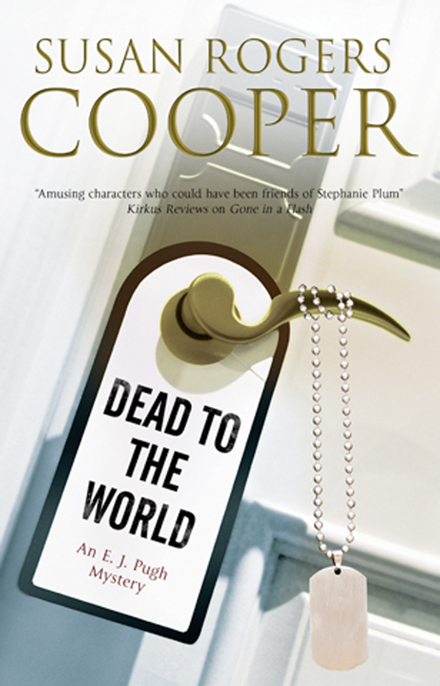

Dead to the World

Authors: Susan Rogers Cooper

Table of Contents

The E.J. Pugh Mysteries

ONE, TWO, WHAT DID DADDY DO?

HICKORY DICKORY STALK

HOME AGAIN, HOME AGAIN

THERE WAS A LITTLE GIRL

A CROOKED LITTLE HOUSE

NOT IN MY BACK YARD

DON’T DRINK THE WATER

ROMANCED TO DEATH *

FULL CIRCLE *

DEAD WEIGHT *

GONE IN A FLASH *

DEAD TO THE WORLD *

THE MAN IN THE GREEN CHEVY

HOUSTON IN THE REARVIEW MIRROR

OTHER PEOPLE’S HOUSES

CHASING AWAY THE DEVIL

DEAD MOON ON THE RISE

DOCTORS AND LAWYERS AND SUCH

LYING WONDERS

VEGAS NERVE

SHOTGUN WEDDING *

RUDE AWAKENING *

HUSBAND AND WIVES *

DARK WATERS *

*available from Severn House

AN E.J. PUGH MYSTERY

Susan Rogers Cooper

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

This first world edition published 2014

in Great Britain and 2015 in the USA by

SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD of

19 Cedar Road, Sutton, Surrey, England, SM2 5DA.

Trade paperback edition first published 2015 in Great

Britain and the USA by SEVERN HOUSE PUBLISHERS LTD.

eBook edition first published in 2014 by Severn House Digital

an imprint of Severn House Publishers Limited

Copyright © 2014 by Susan Rogers Cooper

The right of Susan Rogers Cooper to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Cooper, Susan Rogers author.

Dead to the world.–(An E.J. Pugh mystery)

1. Pugh, E.J. (Fictitious character)–Fiction.

2. Murder–Investigation–Texas–Fiction. 3. Psychics–

Fiction. 4. Women novelists–Fiction. 5. Women private

investigators–United States–Fiction. 6. Detective and

mystery stories.

I. Title II. Series

813.6-dc23

ISBN-13: 978-0-7278-8458-9 (cased)

ISBN-13: 978-1-84751-559-9 (trade paper)

ISBN-13: 978-1-78010-607-6 (e-book)

Except where actual historical events and characters are being described for the storyline of this novel, all situations in this publication are fictitious and any resemblance to living persons is purely coincidental.

This ebook produced by

Palimpsest Book Production Limited, Falkirk,

Stirlingshire, Scotland.

This book is dedicated to the late

Warrant Officer George Rogers, USMC, Rt.,

my dad,

who was a China Marine.

I’d like to thank the

Leatherneck

archives and the

Marine Corps Gazette

for the history lesson. Any change in fact was for the story, or my own fault. I’d also like to thank Joan Hess for her invaluable assistance during gab fests, Jan Grape for her invaluable input, and my daughter Evin Cooper for keeping me on track. As always, thanks to my agent, Vicky Bijur, and my editor, Sara Porter.

DECEMBER, 1947

C

arrie Marie Hutchins came home from school that day full of gossip to tell her mother. Mama loved to hear the goings-on at the school, especially about the teachers and the lunch-room ladies, even though Mama had taken to her bed with the vapors. She’d been up in her room ever since they’d got that telegram from the War Office telling them how Daddy had been killed on D-Day.

Home was a two-and-a-half story, gingerbread Victorian that had belonged to Mama’s mama and her mama before her, built by Carrie Marie’s great-great-great grandfather, who had come to Texas from Tennessee when he was only eighteen and Texas was still its own country. Carrie Marie loved the high ceilings that echoed and the wood floors that made her shoes sound like tap shoes. She loved that Mama didn’t mind if she rode the bannister down from the second floor, as long as she didn’t do it in front of company.

But they hadn’t had company for a while now, not since the telegram from the War Office. People had come by at first with food and stuff; one man had mowed the lawn, and another used his own coupons to fill Daddy’s car up with gasoline. But since Mama didn’t drive, Carrie Marie figured it was sort of a waste of good ration coupons.

That day Carrie Marie ran up the long flight of stairs two at a time, even though Mama said it wasn’t lady-like. She called her mama’s name a couple of times, and was surprised when Mama didn’t call back to her. She rushed into her mama’s bedroom and stopped short.

Carrie Marie’s mama was lying in a bloody heap on the floor next to the bed, her throat slashed. Standing over her was a man with a shiny, bloody thing in his hand. Unfortunately for Carrie Marie’s future, that man was her daddy.

Of course nobody believed her, but the sheriff of Toledo County, Texas, where Carrie Marie’s hometown of Peaceful was, checked with the War Office anyway. They said that not only was Norris Manford Hutchins dead, but they’d sent his dog tags to his widow, Mrs Helen Bishop Hutchins, on January 4, 1945. So word got around and Carrie Marie started getting teased by some of the boys and ostrasized by most of the girls in school. Her only living relative was her daddy’s younger brother, Herbert, who was 4F – medically disqualified – and didn’t serve. He came to live in the old Victorian to look after Carrie Marie, not that he ever did much of that. Mostly he drank whiskey and listened to the radio.

At fifteen, five years after her mama’s death, Carrie Marie couldn’t take school anymore and got her Uncle Herbert to sign the papers for her to quit. She got a job at the Goldman’s Five & Ten in downtown Peaceful, and worked there for twenty-two years, until Mr Goldman died and his children decided to sell the store. But five and dimes were rapidly disappearing by 1972, and the dollar stores were taking over. The one moving into Peaceful was simply called ‘$$’, and Carrie Marie got in line fast and told the person hiring that she’d been the manager of Goldman’s Five & Ten store. Since Mr Goldman’s children had taken the money and gotten the hell out of Peaceful, Carrie Marie figured her little white lie wasn’t going to hurt anybody. She got the job as assistant manager, which was OK with Carrie Marie, because she wasn’t sure exactly what an actual manager did.

And so life went on. Having been born with what they called in those days a ‘withered arm,’ caused by what Carrie Marie finally learned was a birth injury called shoulder dystocia, she hadn’t been real popular with the boys. Add the fact that she had small breasts and a big butt to the withered arm, and there weren’t many – if any – gentleman callers.

Carrie Marie never married, and lived with her Uncle Herbert until he died. He was ninety-seven at the time and Carrie Marie was seventy-four. It was then that she discovered that living off Carrie Marie had been a fairly good thing for her uncle Herbert. Since he didn’t pay rent or buy groceries – other than whiskey – he had managed to squirrel away a hefty sum from his disability payments. When he died he didn’t leave a will, but as Carrie Marie was his only living relative she got everything that was his. And what was his amounted to $74,352.75. It was at this point that Carrie Marie decided to give up her job at the $$ store and add yet another B&B to the town of Peaceful.

And she did OK. She actually made money because of her beautiful home full of the treasures of four generations. That is, until Daddy started showing up again.

W

illis and I take turns planning our anniversary celebration every year. This year was my turn, and since it was the big two-oh – yes, folks, twenty years married to the same man – I was pulling out all the stops. Knowing that in five years it would be our truly significant twenty-fifth, I decided this would be great, yet a little understated. Travel, but within reason. Since we both loved the Texas hill country, that would be my destination. Doing my research, I found the small town of Peaceful, Texas, north of San Antonio, west of Austin and just a smidgen away from Bourne. It was full of antique stores, boutiques and restaurants. All the goodies.

I wanted this to be a surprise, so I packed a suitcase for the two of us and stashed it in the trunk of my Audi TT Roadster (a two-seater I bought with an extra-big book check), and told him we were going for a drive. This was on a Friday afternoon.

Things were OK at home – my three girls are all seventeen now, and my college-aged son has been living with my mother-in-law. We were just going to be gone Friday and Saturday, back on Sunday, and with Elena Luna, our police detective next-door neighbor on the alert, I figured I didn’t need to worry about them getting into too much trouble.

Willis and I got in my beautiful sports car with me driving and headed west. I call him Grandma Willis for his less-than-stellar driving skills. He calls me a stunt driver – which I think is grossly unfair. I never go more than five to ten miles over the speed limit – unless I’m really in a hurry. He sets the cruise control on his Texas clown truck (one of those big trucks balanced on way too big tires that means you have to have a ladder to climb into the damn thing) to the exact speed limit. He also stops at green lights. Not necessarily a complete stop, but irritating none the less. I, on the other hand, spent my formative driving years in Austin at the University of Texas and picked up the Austin rule of thumb concerning traffic lights: it doesn’t matter at what point in the yellow light sequence you are – run it. And a red light is really only slightly more than a suggestion.

Once we were west of Austin, getting into the hill country and its winding roads up and down steep hills, I hit the accelerator and got into some serious driving. It infuriates me when people in front of me have to slam on their brakes for a rolling turn or going down a barely steep hill. I mean, come on folks, you

accelerate

into a turn, and why do you have to stop to go downhill, for God’s sake? Willis, of course, spent the entire time with one hand clutching the door and his left foot raised to the dashboard – which is a feat and a half for a guy who’s six foot three and most of that’s leg.

The convertible top on my Audi was down, the spring sun was shining on us and the wind was kissing my cheeks. I had had my curly copper-red hair chopped off recently so the wind wasn’t going to do much damage on that score. I loved the new do – definitely wash and wear. Get out of the shower, towel it dry, hand comb it, give it a toss and there you go. Willis said it made me look like Little Orphan Annie, but I think he’s just jealous because there’s more hair on the floor of the tub after his shower than on his head.

Being April, the sides of the back roads I was taking had sprung to life with bluebonnets, Indian paint brush, primroses and other Texas wild flowers whose names I didn’t know. Suffice it to say there was a riot of color on both sides of the road, interrupted only by a steep, rocky hill or a large-limbed oak tree, and there was a plethora of both. In front of us we could see hills of all shapes and sizes and, like clouds, you could identify a dog or a rabbit or a guy with a flat-top. The roads swooped up and down, a hair-pen curve here, a ninety-degree turn there. And I made them all going somewhere between seventy and eighty miles an hour. Which, personally, I just don’t think is all that excessive.

At about four in the afternoon we pulled into the outskirts of Peaceful. Like many a small town in Texas (and I’m sure other states as well), the outskirts were scattered with car graveyards, junk dealers, auto repair shops and the like, but once past those we found ourselves in a quaint little village of Sunday houses and ornate cisterns. I knew from my reading that Peaceful was founded by German immigrants, and the ornate cisterns were straight out of the old country. They had stored water before the town had its own reservoir, but were now home to small shops and tea rooms. Some were shaped like small windmills, others patterned after the Sunday house they’d belonged to. For those not in the know on Sunday houses, that was a tradition where wealthy farmers and ranchers would buy a house ‘in town’ and the family would drive in on Saturday, buy whatever supplies they needed, spend the night in their second home and go to church on Sunday.

Our destination, The Bishop’s Inn, was on a street called Post Oak, two blocks off the main thoroughfare, which, strangely enough, was called Main Street and looked just like the pictures I’d seen on their website. The house was a beautiful Victorian in excellent condition, with a garden my black-thumbed self envied beyond reason. We parked in the small parking lot adjacent to the house, and I confessed all to Willis.

‘But I was supposed to play handball with Jim tomorrow!’

‘I told his wife that you had to cancel.’

‘You what?’

I sighed. ‘Willis, this is our twentieth wedding anniversary! Cut me some slack here, OK?’ Had the asshole forgotten it was our anniversary? Was he that big a douche? All the fun was slipping out, quickly replaced with a building anger – and, I’ll admit, a little sadness with a touch of embarrassment.

Then my husband of twenty years grinned at me. ‘Good thing I decided to bring this along on our, excuse the expression, “drive.”’ And he pulled a small box out of one of the pockets of his cargo pants and handed it to me. He did remember! He was just giving me grief, like only he could. I leaned over and kissed him, and he kissed me back, putting a little more into it than you’d think after twenty years. Which was a good thing.

Once that had ceased, I unwrapped the box and opened it. Winking at me from the depths of a ring box was a diamond. I’m not well versed in diamonds, having never had one, but this looked to be at least a full karat. I stared at it – a baguette-shaped solitaire – then up at my husband. Then back at the ring.

‘Wha—’ I started, then stopped.

Willis was shaking his head and laughing. ‘E.J. Pugh, speechless! I never thought I’d live to see the day!’

‘But …’

He took the box out of my hand, removed the ring and held up my left hand. ‘When I asked you to marry me twenty years ago, all I had to give you was that stupid friendship bracelet that your roommate made into a ring for me. And still you said yes. I was looking for something in our bedroom the other day and happened to open that big old jewelry box of yours. There it was – that friendship ring – all the threads losing their color, just sitting there. I couldn’t believe you’d kept it all these years. That’s when I decided it was about time you got a real engagement ring.’

He lifted my ring finger and slid the ring on it. The gold of my wedding band matched the gold of the engagement ring perfectly. And, as if in on a private joke, the diamond winked at me. ‘I love this, Willis,’ I said, and kissed him again, ‘but it doesn’t mean you can touch my original engagement ring! That stays right where it is, you hear?’

He put up his hands in surrender. ‘Jeez, I thought you were only sentimental about the kids!’

I really wasn’t paying that much attention. I was staring at my hand with the beautiful new ring. I really needed to do my nails.

It took a little longer than would seem necessary to get out of the car, grab our one bag and head up the seven steps to the front door of the Bishop’s Inn. The inn itself was painted a subtle gray-blue, with wine-red shutters and white accents. The floor of the deep front porch had been fairly recently painted white and held white rocking chairs and two porch swings, one on each side of the porch. Willis went up to the wine-red door and used the lion’s head knocker.

There was no answer, so he knocked again. Still no answer. He turned and looked at me.

‘We have reservations,’ I said. ‘Try the knob.’

He did and the door swung open into a wide foyer, empty of people but well-appointed with an ornate antique coat rack, an antique grandfather clock and an antique half-circle pedestal table with a cut-glass vase atop it. The vase contained multicolored roses that were beginning to all turn the same shade of dead brown.

‘Hello?’ Willis called out.

‘Miss Hutchins?’ I said. Miss Hutchins, the owner, and I had corresponded through email about the reservation weeks ago.

There were rooms to the right and to the left of the foyer. The room on the right appeared to be a living room/parlor; the one on the left was outfitted as a library. Coming off the library was another room – a formal dining room. As we stepped toward that, we saw the staircase on the right, with a hall between it and the living room that led to more rooms. We heard steps on the staircase and looked up. That’s when we heard a tiny squeak come out of the mouth of the woman descending the stairs.

She was an older lady, probably in her seventies or eighties, with a halo of thinning white hair, fading blue eyes, thin, and with a handicapped right arm. ‘You startled me!’ she said, stopping on the landing, her left hand clutching the area around her heart. ‘Who are you?’

Her voice was thin and reedy, and a little trembly. I said, ‘Miss Hutchins? I’m E.J. Pugh. I emailed about reservations?’

She continued to stare at me for a full minute, then turned to stare at Willis for another minute. Then said: ‘Well.’ She continued to stand where she was – on the landing – still clutching the material of her blouse above her heart.

‘Is there a problem, Miss Hutchins?’ I asked.

‘Problem?’ she said. ‘Well, yes, I guess you might say that.’

‘May we do something to help?’ I asked.

Another minute of staring. Then she said, ‘Thank you, but I don’t really see how you could.’ Tears sprang to her eyes. ‘I don’t think anyone can help.’

I slowly walked up the stairs to the landing and took her by the arm. ‘Let’s go to the kitchen and make some tea, shall we?’ I asked.

We slowly descended the stairs and she replied, ‘I’d prefer a shot of whiskey, but I know you mean well.’

The kitchen was bright yellow with new appliances but old painted cabinets and bright white Formica counter tops. There was a large round claw-foot table in the middle of the room (I’d mention it was an antique, but I have a feeling that word’s going to be a description for almost everything in the house), and we sat down on old ladder-back chairs. She pointed at a cabinet in which I found a bottle of Tennessee sipping whiskey and three glasses, and brought it all to the table. I poured each of us two fingers, then the old lady took the bottle from me and added two more to her glass.

‘I’m not much of a drinker,’ she said and downed the glass. ‘But lately it seems like the best solution.’

I lifted my glass and smelled the whiskey. It made me want to throw up. I set it back down. Give me a nice daiquiri or a tequila sunrise, but straight whiskey? Not my poison of choice.

I touched the old lady’s hand. ‘What’s the problem, Miss Hutchins?’ I asked.

She squeezed my hand. ‘Call me Carrie Marie,’ she said, and tried a tentative smile. Her false teeth were an awesome white even against her pale skin. ‘Well, you see, my daddy has come back. Which is a hell of a problem.’

Willis and I looked at each other – both thinking the obvious, I’m sure. At her age, her ‘daddy’ had to be in his hundreds, right?

‘Your daddy?’ Willis said. ‘You mean your father or your husband?’

Carrie Marie gave him a horrified look. ‘My father, of course! That’s just sick!’

‘Oh, no, ma’am,’ Willis started, ‘I mean—’

‘Young man, I think you’ve said enough,’ the old woman said, and turned her face away from Willis.

‘He meant no disrespect,’ I said quietly. ‘It’s just that some women call their husbands daddy.’

She looked from me to Willis and back to me. ‘Why in the world would they do that?’ she asked, her faded blue eyes big and round.

I shrugged. ‘I have no idea, but some do.’

‘Well, I’ve never married,’ she said, and pointed at her disfigured arm. ‘Men don’t like girls who aren’t whole, you know.’

I started to open my mouth to confront her with the political incorrectness of her statement, then thought better of it. ‘So let’s get back to your daddy being back,’ I suggested.

‘Certainly,’ she said. ‘Well, first, you know, he killed Mama back in ’forty-five—’

‘Excuse me?’ Willis said.

Carrie Marie looked at my husband and proceeded to repeat herself slowly and succinctly. ‘He. Killed. My. Mother. In nineteen forty-five.’

‘I’m so sorry, Carrie Marie!’ I said. ‘That must have been awful!’

‘Oh, it was,’ she said, filling her glass yet again with the Tennessee sipping whiskey. ‘I found her body and him standing over her with a knife or something in his hand.’ She took a long sip and nodded her head. ‘Yep. Awful is a good word for it.’

‘Is he out of prison now?’ Willis asked.

‘Prison?’ she repeated. ‘Oh, no! He didn’t go to prison. Nobody believed me when I told ’em my daddy killed her.’

‘Why not?’ I asked.

She drained her second glass (I was losing track of the finger amount) and said, ‘’Cause he got killed on D-Day. We were sent his dog tags and everything. Still got ’em. And they say there was no mistake.’

‘So he went to war after he killed your mother?’ Willis asked, a frown on his handsome face.

‘No, no,’ she said. ‘Mama died after we got the telegram from the War Office. Gosh, it had to have been close to eighteen months since D-Day.’

‘Then how—’ Willis started.

Carrie Marie looked around the room, as if to make sure we weren’t going to be overheard, and whispered, ‘’Cause it’s my daddy’s spirit, y’all! He’d come back from the dead. And now he’s back again!’

Not much later we were in a suite on the second floor. There was a sitting room with a camel-backed sofa and an easy chair, both covered in a blue willow-patterned brocade. Two paintings of blue bonnets graced one wall, while a second held large windows and a French door leading to a balcony overlooking the back garden. The bedroom held an antique four-poster bed that had been adjusted to queen-size, and covered with a blue willow-patterned comforter. A second wall of windows overlooked a side garden. The bathroom was one door down and contained the largest claw-footed bathtub I’d ever seen, with a toilet that had a chain one used to flush. Being early spring, Miss Bishop had opened the windows to air the room out before leaving us alone.