Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All (20 page)

Read Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All Online

Authors: Paul A. Offit M.D.

BOOK: Deadly Choices: How the Anti-Vaccine Movement Threatens Us All

13.38Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The spirit of Mary Hume-Rothery is alive today in Debi Vinnedge, founder of Children of God for Life in Largo, Florida. Vinnedge is angry that two human cell strains—which could be used to make vaccines for the next several centuries—were obtained from voluntary abortions in the early 1960s. These cell lines are used to make vaccines for rubella, chickenpox, hepatitis A, and rabies. Vinnedge refuses to accept a product made using cells from an abortion, an act worthy of excommunication. “Casually accepting the use of aborted fetal cell lines in medical treatments has been a blatant disgrace to humanity,” she has said, “a despicable sullying of the value and dignity of human life, and has lent credibility to the gross commercialization of aborted babies, ripped from their mother’s womb so that someone could turn a profit. We must not become slaves to the Culture of Death. Using aborted babies as products to help those children fortunate enough to not have their lives snuffed out pre-birth is akin to the most vile form of cannibalism imaginable. Yet we are asked to accept it for every polite reason except one that begs the question: ‘What kind of a civilization have we really progressed to when we can find no better way to protect ourselves than by using the remains of murdered children?’” Vinnedge has lobbied the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy for Life without success—the Vatican arguing that vaccines using cell lines originally obtained from elective abortions promote the greater good by preventing life-threatening infections. (Ironically, because natural rubella infections during pregnancy led to thousands of spontaneous abortions every year, the rubella vaccine, like the Catholic Church, has prevented many abortions.)

Mass-marketing:

Anti-vaccine activists in Victorian England took advantage of an increasingly print-oriented society. They produced hundreds of different handbills and pamphlets; engaged in letter-writing campaigns to local and national newspapers; distributed several periodicals throughout England and Wales; hung posters in shop-windows to encourage citizens to talk about the dangers of vaccines; and produced grotesque, graphic photographs of children supposedly harmed by vaccination, perhaps the most disturbing of which was a child suffering from cancer of the eye. The editor of the

British Medical Journal

, Ernest Hart, lamented the success of the antivaccine message. “[Anti-vaccine activists have] an extremely energetic system of distributing tracts, inflammatory postcards, grotesquely drawn envelopes, and other means of disseminating their views.” On the other hand, those who were promoting the value of vaccines didn’t offer “an accessible antidote to these productions.”

Anti-vaccine activists in Victorian England took advantage of an increasingly print-oriented society. They produced hundreds of different handbills and pamphlets; engaged in letter-writing campaigns to local and national newspapers; distributed several periodicals throughout England and Wales; hung posters in shop-windows to encourage citizens to talk about the dangers of vaccines; and produced grotesque, graphic photographs of children supposedly harmed by vaccination, perhaps the most disturbing of which was a child suffering from cancer of the eye. The editor of the

British Medical Journal

, Ernest Hart, lamented the success of the antivaccine message. “[Anti-vaccine activists have] an extremely energetic system of distributing tracts, inflammatory postcards, grotesquely drawn envelopes, and other means of disseminating their views.” On the other hand, those who were promoting the value of vaccines didn’t offer “an accessible antidote to these productions.”

Today’s methods of mass communication include national television programs, Web logs, YouTube, and Twitter. Through these outlets anti-vaccine activists have been able to get their message to millions of people quickly and cheaply. And they’re much better at it than public health officials, doctors, and scientists. Rahul Parikh, a pediatrician in Walnut Creek, California, offered a lament in 2008 that echoed the words of Ernest Hart a hundred and fifty years earlier. In an editorial titled “Fighting for the Reputation of Vaccines,” Parikh wrote, “Anti-vaccine groups are well organized and passionate. They have used popular settings such as

Oprah

and

Larry King Live

to make strong emotional appeals and get parents to think twice about having their children vaccinated. People, logical or not, do not forget this kind of emotional prowess. On the other hand, our medical and scientific experts counter with accurate evidence and citations of studies, which do not resonate with many parents. Dispassionate messages are not sticky. Gut-wrenching stories ... are. It is time we change.”

Oprah

and

Larry King Live

to make strong emotional appeals and get parents to think twice about having their children vaccinated. People, logical or not, do not forget this kind of emotional prowess. On the other hand, our medical and scientific experts counter with accurate evidence and citations of studies, which do not resonate with many parents. Dispassionate messages are not sticky. Gut-wrenching stories ... are. It is time we change.”

Although the anti-vaccine movement in the mid-1800s is similar to today’s, certain differences are striking.

Rich versus poor:

Laws compelling vaccination in nineteenth-century England were directed against the poor. Authorities believed that the working class, because it was less educated, would be more likely to fear vaccines and less likely to get them. As a consequence, resistance to vaccination sprang up in working-class neighborhoods in East and South London as well as in heavily industrialized towns such as Manchester, Sheffield, and Liverpool. Resisters were primarily journeymen laborers, artisans, factory workers, and small shopkeepers—groups most likely to suffer the public humiliation of vaccine stations.

Laws compelling vaccination in nineteenth-century England were directed against the poor. Authorities believed that the working class, because it was less educated, would be more likely to fear vaccines and less likely to get them. As a consequence, resistance to vaccination sprang up in working-class neighborhoods in East and South London as well as in heavily industrialized towns such as Manchester, Sheffield, and Liverpool. Resisters were primarily journeymen laborers, artisans, factory workers, and small shopkeepers—groups most likely to suffer the public humiliation of vaccine stations.

Today, on the other hand, resistance to vaccines is found in the upper-middle class among parents who are college- and graduate-school-educated, likely to use the Internet to make healthcare decisions, and fully believing that they, too, can become experts in an information age. The problem, however, lies in how they obtain their expertise. Magazine and newspaper articles and the Internet often provide information that is misleading and unnecessarily frightening. And it’s not hard to find like-minded people on the Internet, no matter how small the group or how outlandish the belief.

Lawyers:

Unlike anti-vaccine protesters in Victorian England, some of today’s anti-vaccine activists find a pot of gold at the end of the injury-compensation-program rainbow. Fear of pertussis vaccine in the 1980s led to millions of dollars in awards and settlements. As a consequence, anti-vaccine organizations now work hand-in-glove with personal-injury lawyers, many of whom sit on their advisory boards and help them prepare pamphlets that warn of the dangers of vaccines and describe how to collect money. For example, a press release by Barbara Loe Fisher’s National Vaccine Information Center quotes Michael Kerensky, a lawyer from one of the most powerful product-liability law firms in the United States. At the end of the press release is this statement: “In cooperation with the National Vaccine Information Center, Kerensky has developed an educational pamphlet about the National Vaccine Compensation Fund. To request a copy call 1-800-245-0249.” Fisher’s Web site provides direct links to sixteen personal-injury law firms.

Unlike anti-vaccine protesters in Victorian England, some of today’s anti-vaccine activists find a pot of gold at the end of the injury-compensation-program rainbow. Fear of pertussis vaccine in the 1980s led to millions of dollars in awards and settlements. As a consequence, anti-vaccine organizations now work hand-in-glove with personal-injury lawyers, many of whom sit on their advisory boards and help them prepare pamphlets that warn of the dangers of vaccines and describe how to collect money. For example, a press release by Barbara Loe Fisher’s National Vaccine Information Center quotes Michael Kerensky, a lawyer from one of the most powerful product-liability law firms in the United States. At the end of the press release is this statement: “In cooperation with the National Vaccine Information Center, Kerensky has developed an educational pamphlet about the National Vaccine Compensation Fund. To request a copy call 1-800-245-0249.” Fisher’s Web site provides direct links to sixteen personal-injury law firms.

Marketing strategy:

Protesters in nineteenth-century England had no trouble labeling themselves anti-vaccine. Indeed, most organized anti-vaccine groups included the word

anti-vaccination

in their names. Today, however, anti-vaccine activists go out of their way to claim that they are not anti-vaccine; they’re pro-vaccine. They just want vaccines to be safer. This is a much softer, less radical, more tolerable message, allowing them greater access to the media. However, because anti-vaccine activists today define

safe

as free from side effects such as autism, learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, strokes, heart attacks, and blood clots—conditions that aren’t caused by vaccines—safer vaccines, using their definition, can never be made.

Protesters in nineteenth-century England had no trouble labeling themselves anti-vaccine. Indeed, most organized anti-vaccine groups included the word

anti-vaccination

in their names. Today, however, anti-vaccine activists go out of their way to claim that they are not anti-vaccine; they’re pro-vaccine. They just want vaccines to be safer. This is a much softer, less radical, more tolerable message, allowing them greater access to the media. However, because anti-vaccine activists today define

safe

as free from side effects such as autism, learning disabilities, attention deficit disorder, multiple sclerosis, diabetes, strokes, heart attacks, and blood clots—conditions that aren’t caused by vaccines—safer vaccines, using their definition, can never be made.

In 1898, the British government finally gave in, appeasing angry citizens by passing a conscientious-objection law. People who didn’t want to get a vaccine didn’t have to. (The term

conscientious objector

, born of England’s anti-vaccine movement, was later applied to those who refused to fight in World War I and subsequent wars.) Within a year, the government issued more than two hundred thousand certificates of conscientious objection. By the late 1890s, vaccination rates had plummeted. In Leicester 80 percent of babies were unvaccinated; in Bedfordshire, 79 percent; in Northamptonshire, 69 percent; in Nottinghamshire, 50 percent; and in Derbyshire, 48 percent. Anti-vaccine forces in England had won the day. In Ireland and Scotland, on the other hand, no such movement existed. No anti-vaccine groups were formed, no anti-vaccine pamphlets were produced, and citizens readily accepted vaccination. While vaccination rates in England fell, those in Scotland and Ireland rose. As a result, England became Europe’s epicenter of smallpox disease and death.

conscientious objector

, born of England’s anti-vaccine movement, was later applied to those who refused to fight in World War I and subsequent wars.) Within a year, the government issued more than two hundred thousand certificates of conscientious objection. By the late 1890s, vaccination rates had plummeted. In Leicester 80 percent of babies were unvaccinated; in Bedfordshire, 79 percent; in Northamptonshire, 69 percent; in Nottinghamshire, 50 percent; and in Derbyshire, 48 percent. Anti-vaccine forces in England had won the day. In Ireland and Scotland, on the other hand, no such movement existed. No anti-vaccine groups were formed, no anti-vaccine pamphlets were produced, and citizens readily accepted vaccination. While vaccination rates in England fell, those in Scotland and Ireland rose. As a result, England became Europe’s epicenter of smallpox disease and death.

For anti-vaccine activists in England, the freedom to choose had become the freedom to die from that choice. As in nineteenth-century England, the battle to eliminate vaccine mandates in twenty-first-century America would also be fought in legislatures and court-rooms. And the results would be all too similar.

CHAPTER 8

Tragedy of the Commons

Freedom is the recognition of necessity.

—

GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH HEGEL

GEORG WILHELM FRIEDRICH HEGEL

P

arents in nineteenth-century England argued that vaccines were impure or unsafe or an act against nature or God. But their anger wasn’t directed at doctors so much as at government officials who had no right to tell them what to do—no right to tell them what should be injected into their children. To protesters, compulsory vaccination was an intolerable violation of their civil liberties.

arents in nineteenth-century England argued that vaccines were impure or unsafe or an act against nature or God. But their anger wasn’t directed at doctors so much as at government officials who had no right to tell them what to do—no right to tell them what should be injected into their children. To protesters, compulsory vaccination was an intolerable violation of their civil liberties.

In America, the response to state-mandated vaccines was no different. Indeed, one citizen’s fight went all the way to the Supreme Court. The ruling in that case—called “the most important Supreme Court case in the history of American public health”—has been cited in seventy Supreme Court verdicts and, for more than a century, has determined whether states can force parents to vaccinate their children.

It started with a Lutheran minister in Massachusetts.

In May 1899, a case of smallpox occurred in the city of Swamp-scott, twelve miles outside Boston. By summer, several more cases appeared in Everett and Charlestown, just across the Charles River. By 1901, more than two hundred Bostonians had fallen victim to the disease. In response, the Cambridge Board of Health proclaimed: “Whereas, smallpox has been prevalent in this city of Cambridge and has continued to increase; and whereas it is necessary for the speedy extermination of the disease; be it ordered that all inhabitants of the city be vaccinated.” Citizens who refused were fined $5.00. By early 1902, more than 485,000 had been vaccinated. The

Boston Daily Globe

declared, “There is a greater demand for vaccination in Boston than there is for salvation, even though both are free.” In 1903, when the epidemic ended, smallpox had infected sixteen hundred people and killed almost three hundred. If city health officials hadn’t acted, the toll would have been much greater.

Boston Daily Globe

declared, “There is a greater demand for vaccination in Boston than there is for salvation, even though both are free.” In 1903, when the epidemic ended, smallpox had infected sixteen hundred people and killed almost three hundred. If city health officials hadn’t acted, the toll would have been much greater.

Not everyone embraced the city’s mandate. On March 15, 1902, Dr. Edwin Spencer visited the home of Henning Jacobson and offered to vaccinate him. Jacobson refused—then he refused to pay the fine.

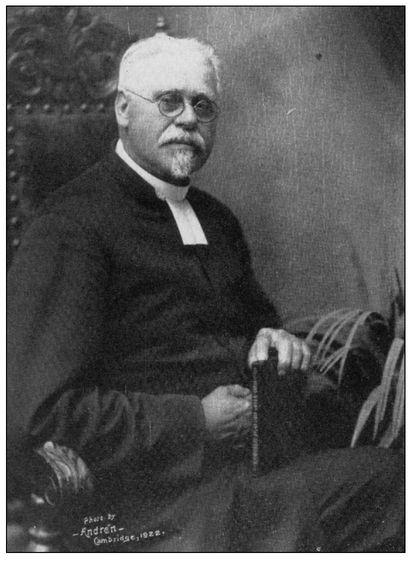

Henning Jacobson was born in Sweden in 1856, coming to the United States when he was thirteen years old. In 1882, while a student at a Lutheran college in Minnesota, Jacobson married Hattie Alexander and together they had five children. In 1893, the Church of Sweden Mission Board asked him to found a Lutheran church in Cambridge, Massachusetts. A pious man, charismatic orator, and community organizer, Jacobson was devoted to his congregants; his fundamental belief that God would protect him was at the heart of his refusal to vaccinate.

In July 1902, Jacobson was tried before a Middlesex county district court. After a jury found him guilty, Jacobson appealed to the county’s superior court, which, in February 1903, upheld the conviction. Undeterred, Jacobson appealed to the state supreme court. This time, two well-known lawyers represented him: Henry Ballard of Vermont and James Pickering, a Harvard-trained lawyer who would later win fame as the oldest U.S. soldier in World War I. Given their fees and his meager pastor’s salary, Jacobson’s choice of Ballard and Pickering was surprising. But Pickering lived only a few blocks from Immanuel Pfeiffer, a leader of Boston’s Anti-Vaccination League. It was Pfeiffer who had convinced Pickering to take the case.

Pickering and Ballard argued that the state had violated Jacobson’s civil rights: “Can the free citizen of Massachusetts, who is not yet a pagan, not an idolator, be compelled to undergo this rite and to participate in this new—no, revised—form of worship of the Sacred Cow?” Again, Jacobson lost. So he took his case to the highest court in the land. On June 29, 1903, the United States Supreme Court added

Jacobson v. Massachusetts

to its docket. This time Jacobson chose George Williams, a former congressman from Massachusetts, to represent him. Williams argued that Massachusetts, by requiring vaccination, had violated the Fourteenth Amendment—specifically, that no state could deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Williams’s legal brief stated, “A compulsory vaccination law is unreasonable, arbitrary, and oppressive, and, therefore, hostile to the inherent right of every freeman to care for his own body and health in such a way as to him seems best.” Williams also argued that vaccines were unconscionably dangerous: “We have on our statute book a law that compels ... a man to offer up his body to pollution and filth and disease; that compels him to submit to a barbarous ceremonial of blood-poisoning, and virtually to say to a sick calf, ‘Thou art my savior; in thee I do trust.’”

Jacobson v. Massachusetts

to its docket. This time Jacobson chose George Williams, a former congressman from Massachusetts, to represent him. Williams argued that Massachusetts, by requiring vaccination, had violated the Fourteenth Amendment—specifically, that no state could deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. Williams’s legal brief stated, “A compulsory vaccination law is unreasonable, arbitrary, and oppressive, and, therefore, hostile to the inherent right of every freeman to care for his own body and health in such a way as to him seems best.” Williams also argued that vaccines were unconscionably dangerous: “We have on our statute book a law that compels ... a man to offer up his body to pollution and filth and disease; that compels him to submit to a barbarous ceremonial of blood-poisoning, and virtually to say to a sick calf, ‘Thou art my savior; in thee I do trust.’”

Other books

If Truth Be Told: A Monk's Memoir by Om Swami

Love @ First Site by Jane Moore

No Small Victory by Connie Brummel Crook

Showstopper by Pogrebin, Abigail

Holiday Bound by Beth Kery

The Twisting by Laurel Wanrow

Those Jensen Boys! by William W. Johnstone

Another Life by Michael Korda

Demonfire by Kate Douglas