Deadly Little Games (6 page)

DOCTOR:

So, I wanted to ask you about something that came up during our last session. What did you mean when you said that you can force someone to love you?PATIENT:

I meant just what I said: if you want someone badly enough, you can make them yours.DOCTOR:

Even if they don’t want to be with you?PATIENT:

Sure.DOCTOR:

Have you ever tried?PATIENT:

Not yet.DOCTOR:

Do you plan to try?PATIENT:

I don’t know.

(Patient laughs.)DOCTOR:

Why is that funnyPATIENT:

This whole conversation’s funny.DOCTOR:

Forcing someone to do something they don’t want to is hardly amusing…at least, not to me.PATIENT:

Sometimes people don’t know what they want. Sometimes they need to suffer a little to understand what’s really good for them.DOCTOR:

Did that work in your case?PATIENT:

What do you mean?DOCTOR:

Did the suffering your father made you endure help you to see what you truly wanted?PATIENT:

It helped me to see what I

don’t

want.DOCTOR:

So, what makes you think that forcing someone to do something against his or her will won’t have the same effect that it did on you?PATIENT:

(Patient doesn’t respond.)DOCTOR:

Do you want to talk about your suffering?PATIENT:

There’s not too much to talk about. My father used to beat me. My mother looked the other way.DOCTOR:

And now?PATIENT:

Now I don’t really see my father anymore. And my mother basically ignores me.DOCTOR:

So, where does that leave you?PATIENT:

Pretty messed up, I guess.

(Patient laughs.)DOCTOR:

You’re laughing again.PATIENT:

Sorry, I just think this whole scenario is pretty funny.DOCTOR:

How so?PATIENT:

I mean, if anyone actually knew what I’ve got going on inside my brain…DOCTOR:

Care to enlighten me?PATIENT:

Not really. You’ll just have to wait and see, like everybody else.

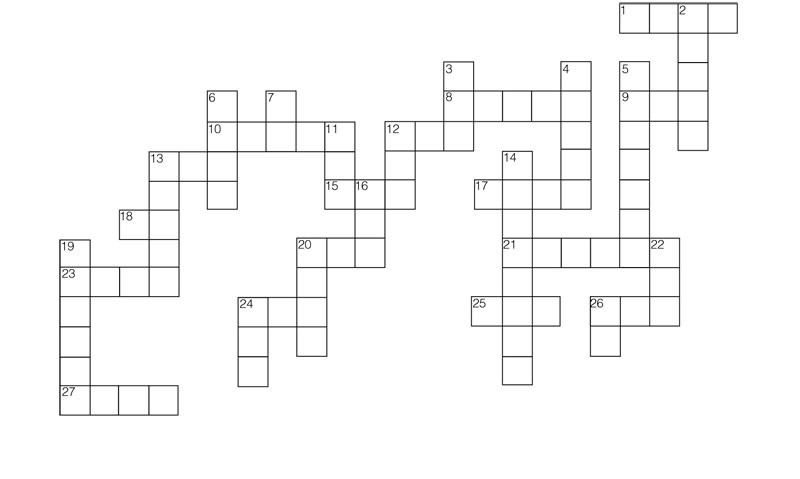

Across

18.

I am alone. There’s only ________.

20.

Sometimes I truly hate ________.

23.

When he ________, I cut out his tongue.

Down

3.

A couple minus ________ = no one.

O

NCE WE LAND IN

Detroit, instead of checking in at our bed-and-breakfast first, we get a rental car and drive straight to the facility where Aunt Alexia is staying. It’s after nine, so I’m thinking visiting hours are over for the day, but Mom insists that because we’re family we have every right to see her right away.

The facility is nothing like what I imagined—ironically, it’s more like a funeral home, a place to bring the dead, than a place to keep the suicidal from dying. We pull up in front of a long brick walkway that leads to a giant white house. Spotlights and a lamppost illuminate the area, but there’s no sign out front, and all the window shades are drawn. Mom puts the car in park, and we head to the main entrance.

An older woman greets us, introducing herself as Ms.

Connolly, the head nurse. She invites us inside, and the funeral-home vibe persists—mahogany woodwork, shelves full of old and dusty books, and antique-looking furniture.

“It’s uncanny,” Ms. Connolly says, giving me the once-over. “You look just like your aunt. If I didn’t know better, I’d say you could almost be sisters.”

“Can we see Alexia?” Mom asks, wanting to avoid the small talk. Her hands are shaking, and she can’t stop fussing with her scarf. And suddenly I’m nervous, too.

“I’m sorry,” Ms. Connolly says. “But Alexia had a tough day today and she was put to bed after dinner.”

“What does that mean?” Mom asks.

“She was given a little something to help her sleep,” Ms. Connolly explains.

“But I don’t understand. She knew we were coming.”

The woman nods. Her beady black eyes narrow, and she sucks in her lips, making the truth pretty apparent—that it’s

because

of our visit that Aunt Alexia’s day was rough.

“I see,” Mom says, clenching her teeth.

Ms. Connolly musters an encouraging smile. “I’m sure she’ll be more prepared to see you tomorrow morning.”

Mom spends another good fifteen minutes or so continuing to try to get us in, but Ms. Connolly doesn’t cave. She doesn’t even flinch.

Meanwhile, a female voice screeches from down the hallway: “I want my pillow! Just give me my goddamned pillow!” At the same moment, something smacks against the hallway door with a loud, hard crash that makes me jump.

Definitely our cue to leave.

Mom drives us to our B and B for the night. I try to get her to talk about stuff—about how frustrating the situation is and how stressed Aunt Alexia must be. But Mom doesn’t want to hear any of it. Instead she takes what would have to be the longest shower in the history of water, and then heads straight to bed with barely a good night, never mind her nightly sun salutations.

Before I go to bed myself, I check my phone for messages. I have one missed call from Ben. It seems he phoned just before I boarded the plane, but he didn’t leave a message.

Part of me wonders if it was to wish me well once again. Another part secretly hopes that it was to ask me not to go. I’m tempted to call him back to find out the answer. But I follow my mother’s lead instead, and drift off to sleep.

After breakfast the following morning, Mom and I head straight to the hospital to see Aunt Alexia. This time we’re allowed to stay. There’s actually a meeting set up for Mom, Aunt Alexia, and her doctor. Mom asks me if I want to wait in the lobby, but the thought of sitting amid all that funeral-home decor, coupled with the threat of hearing someone screech about her missing pillow, is far more unsettling than the idea of spending the morning by myself in an unfamiliar city. And so I take Ms. Connolly’s advice and head to the strip mall down the road.

A couple of hours later, Mom and I meet up for lunch at a nearby coffee shop.

“So, how was it?” I ask her.

“Good.” She actually smiles—the first smile I’ve seen on her in days. “Her doctor asked me some stuff about our childhood, so I got to tell my side of things.”

“Did Aunt Alexia tell hers?”

Mom shakes her head. “She mostly just listened. But that’s okay, too. Because at least she knows how sorry I am.”

“Even though it wasn’t your fault.”

My mom nods, but I’m not sure she believes it. Growing up, Aunt Alexia was hated by their mother—my grandmother. According to Aunt Alexia’s diary, and confirmed by a few details from Mom, my grandmother blamed Aunt Alexia’s birth as the reason her husband left them. Meanwhile, my mom was loved and indulged, often as a way to make Aunt Alexia jealous.

“She really wants to see you,” Mom says.

I take a bite of scone, thinking back to the last time I saw Aunt Alexia—probably when I was around seven or eight. She came to visit for the holidays, but then left on the afternoon of Christmas Eve.

I remember how nervous she was—always looking over her shoulder, forever checking out the window and fussing with her hair. And I remember all the art supplies she brought along. I wanted her to teach me what she knew, wanted to be able to do brushstrokes just like hers, but Aunt Alexia wouldn’t let me join in, insisting that art was for bad girls, and that I was better off playing with my dolls.

She left soon after, even though Mom begged her to stay. She just kept saying that she needed to get home for an interview she’d forgotten about. Finally, Mom caved and drove her to the train station.

We got a call from the local hospital a few hours later. Aunt Alexia never got on her train. Instead she ended up at the motel in the next town over, where she tried to kill herself, using some telephone cord to hang herself in the shower. Another guest at the motel had heard some weird noises coming from her room and asked the manager to check things out. That’s when they found Aunt Alexia, thankfully in time to save her.

“Just think about it,” Mom says to me. “No pressure.”

“I want to see her. That’s why I’m here.”

Mom reaches across the table to squeeze my hand. “When I brought up your name, she said she remembered how much you liked to watch her paint. I told her that you were an artist as well, and she asked if you’d like to see some of her work.”

“She wasn’t upset?”

“Why would she be?”

I shrug, still wondering what Aunt Alexia meant years ago when she told me that art was for bad girls. Was it a lame attempt to try to get me interested in other things? Was she afraid that I might end up like her?

“When can I see her?” I ask.

“How about after lunch? We leave tomorrow, so we need to take advantage of every moment.”

“Sounds good,” I say, eager to find out some answers.

B

ACK INSIDE THE FACILITY

, Mom explains that this is an alternative place, that they give the patients a lot of liberties that bigger facilities don’t.

“For example?” I ask, closing the door behind us.

Before she can answer, Ms. Connolly appears. She ushers us through the lobby and into an art studio, as if things have all been arranged. “This is the art therapy room,” Ms. Connolly says, opening the door wide.

The ceilings are high. The smell of turpentine is thick in the air. And the room is set up with easels, drop cloths, and the requisite bowl of wax fruit as a centerpiece to paint (only, unlike the wax-fruit arrangement at school, this one has a bite out of one of the apples).

I continue to look around, finally noticing that we’re not alone, that someone’s working in the corner, only partially obscured by a canvas.

It’s Aunt Alexia. I’d recognize her anywhere. She has long and wavy pale blond hair and wide green eyes that stare in our direction.

“Do you want to come and say hello?” Ms. Connolly asks her.

Alexia takes a couple of steps toward us. She’s much tinier than I remember. She’s only a few years younger than my mother, and yet she almost looks like a little girl. Her outfit—a cotton dress with billowing sleeves—drapes her body, almost like a drop cloth itself.

“Do you remember me?” she asks. The angles of her cheeks are sharp, and her mouth looks like a tiny pink seashell.

I nod, and she comes closer. “You’re an artist, your mother tells me.”

“Well, I’m not really sure I’d go that far.”

“You’re an artist,” she repeats, nearly cutting me off. Her voice is like tinkling wind chimes.

“I was telling Aunt Alexia about your pottery,” Mom explains.

Alexia wipes her paint-covered fingers on the front of her apron, producing a bright red smear that makes it look as if she were bleeding from the chest. She extends her hand for me to shake. I try to let go after a couple of seconds, but instead she pulls me across the room toward her canvas, eager to show me her work.

“I’ve been waiting to get your opinion on this one,” she says, picking a canvas up off the floor. She turns it over so I can see.

It’s a painting of a boy, with an undeniable resemblance to Adam—same wavy brown hair, same olive skin. Dark brown eyes, dimple in his chin, scar on his lower lip.

“Interesting, isn’t it?” she says, checking for my reaction.

I swallow hard, not quite knowing how to respond.

“I painted it yesterday,” she continues. “When I heard you were coming, I went to my photo album and took out a picture of you—one that your mother had recently sent me. I touched the photo, and the image of this boy popped into my head.” She nods toward the painting. “Has that ever happened to you?”

Instead of answering, I glance at my mother. She wipes her eyes with a tissue, perhaps moved to see that Aunt Alexia and I have something in common.

If only she knew how much.

“I was hoping to show this to you last night,” Aunt Alexia explains, “when you first arrived. But unfortunately, things got a little detoured the further I got into my work.”

“Oh,” I say, wondering what

detoured

means, exactly, and if that’s the reason she was

put to bed

.

“Do you remember the last time I came to visit you?” she asks, narrowing her eyes, as if trying to read my mind. “We never did get to paint together, did we?”

“No,” I whisper, and look away.

“So, would you like to paint together now?” She looks to my mother for approval.

“It’s up to Camelia,” Mom says.

“I’m not really much of a painter,” I say, for lack of a better excuse.

“It’s easy when you use your hands.” She flashes me her paint-stained palms. “You use your hands with sculpture, too, right?”

“I suppose.”

“Well, you have to admit, there’s nothing quite like sinking your fingers into your work—becoming one with what you create…with what you touch.”

“Your mother and I will stay in the studio as well,” Ms. Connolly assures me.

I take a deep breath, thoroughly confused. But then I look toward the portrait of Adam again, and know that I have no other choice.