Death: A Life (21 page)

Eventually, as the Sphinx’s riddle claimed more and more lives, a desperate appeal was sent to Oedipus, the fabled eccentric, who had married his own mother so that he would never have to clean up his bedroom ever again (although it did mean he had to be in bed by seven o’clock). After some thought, a tantrum, and a little surreptitious help from his wife, Oedipus told the Sphinx that the answer was “man” (“an octopus with a limp” would also have been acceptable).

The Sphinx, however, was not satisfied.

“When is a door not a door?” it snapped.

“When it’s ajar,” replied Oedipus quickly.

“What’s brown and sounds like a bell?”

“Dung.”

“What’s black and white and red all over?”

“A zebra with sunburn.”

Oedipus: “Why Don’t You Tell Me About

Your

Mother.”

“Why is six afraid of seven?”

“Because seven eight nine.”

In desperation the Sphinx finally asked, “What have I got in my pocket?” which was not exactly a riddle according to the ancient rules.

But Oedipus was unfazed.

“You don’t have any pockets,” he said, and the Sphinx, realizing its era was over, threw itself from its rocky perch to its doom.

I asked it afterward, “Why all the questions?”

“What questions?” it replied.

“All the questions you’ve been asking?”

“I was asking questions?”

“Weren’t you?”

“Was I?”

“Did you just say something?”

“Did I just

slay

something?”

This went on for some time.

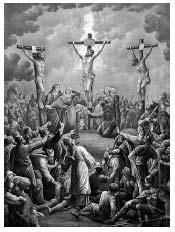

Incident at Golgotha

I

relate

all the previous incidents to you to show you that, after an anxious start, I was quite content with my job. I was surrounded by interesting fatalities, a high mortality rate, and the perennial affection of my beloved Maud. So you can see that it was not unhappiness that made me act the way I eventually did; it was quite the opposite. As I watched tribes rise and fall, empires expand and shrivel, species be born and grow extinct, as I listened to countless last words gasped through innumerable contorted mouths I found myself becoming increasingly engrossed in the plot of Life. I saw how thrilling a Beginning and a Middle could be when combined with my usual province, the End. Increasingly I found myself wanting to be swept up in the whirligig of time, to jump and bound on the mortal coil, to leap aboard the crazy merry-go-round. No, it was not unhappiness that undid me, but delight.

I first noticed something was wrong when the date in the

Book

changed, for no apparent reason, to

A.D.

1. I flicked to the index—no easy thing in a never-ending volume—and saw that there was a “Help” sigil. No sooner had I drawn the sign in the air with my finger than a fat little cherub winged into view from some far-off part of Paradise and fluttered to the ground in front of me. He looked out of breath and unenthusiastic. I showed him the

Book

and he said it was a “revision in the epoch,” a “new eon update,” a “Y-zero problem,” or some such technical jargon, and that it probably wouldn’t affect me in my day-to-day Death. He made me sign a chit and then disappeared. I would soon find out that he was quite wrong—it would affect me very much.

I quickly became distracted from this calendrical peculiarity by the even more peculiar opinions of King Herod of Judea. Herod was entering his dotage and had replaced the sagacity and wisdom of his early years with a paranoid depression centered on the threat posed to his reign by babies.

It was while viewing his own children and their increasing facility at walking and talking that Herod came to the terrifying conclusion that these blubbering bags of mucus, who could barely sit upright and putrefied the air with their effluence, were increasingly coming to resemble actual human beings. Herod’s mind spun wild with the consequences. Soon, he ventured, these physical duplicates would not only start to look like real human beings but might take on human jobs, shop at human markets, grow human beards, and go on to be completely indistinguishable from adult human beings.

Whether Herod’s madness stemmed from the tortures he had suffered at the hands of his own father—whose sadistic nurturing techniques had seen him labeled “the Antipater”—or whether it was just due to his crown being on too tight cannot be known for certain. But the more Herod walked the streets of Judea, the more his suspicions were confirmed. He saw children everywhere growing larger, heard fathers and mothers claiming that their children “would be the death of them,” and saw those same children eventually burying their parents, their faces contorted in adultlike grief. Faced with such evidence, Herod came to the shocking conclusion that if children carried on in this manner they would soon take over the entire world. Gathering his advisers around him, Herod realized that there was only one way to prevent this from happening—kill all the babies in the world.

The Massacre of the Innocents was rather tedious for me, because the souls of babies aren’t the greatest conversationalists. At that time I wanted to hear stories of Life, of love, of experience. Instead I got thousands of tributes to breasts, with the only variation being the preference for right or left.

The Horror! The Horror!

So, to set the scene for my downfall: the Romans were up, the Greeks were down, the Jews were in and out of captivity, the Chinese were building walls, and the Aborigines were eating so many colored mushrooms it was doubtful they were even on this planet at all. It was a warm day in the Middle East and I was touring Earth picking up my usual quota of beggars, lepers, princes, merchants, leeks, kestrels, and kumquats when I found myself drawn to the site of a crucifixion. I knew from experience that there’s no point loitering around these sites waiting for someone to die because the crucified could linger for days. Indeed, there was one occasion when a crucified man lingered for so long he actually got better and went home.

Nevertheless, on that afternoon one of the crucified didn’t look as though He was going to be hanging around for too long at all. He was very pale and had that traditional crucified look on His face—covered in blood, grumpy—but the funny thing was that when I looked in the

Book,

there was no sign of Him. Three people had been crucified that day, yet the

Book

only accounted for the deaths of two of them.

I did a double take. And then a triple one. I could not quite believe what I was seeing. In the millennia of casualties that had come before this, the

Book of Endings

had never made a mistake. It just didn’t happen. Admittedly a few folk have had extremely close brushes with me, but I pride myself on knowing a thing or two about when people are going to die. There’s a certain look they get that pretty much signals it’s my time to shine. Even those who are about to get hit by a bus without knowing it have that look on their faces. It’s a reflex look the body gives when it senses Life’s end hurtling toward it. It’s similar to the kind of look people get when someone hands them a new work project at five o’ clock in the afternoon on a Friday. I call it the five o’ clock shadow of Death. What I’m trying to say is that I

knew

this guy on the cross was toast, but the

Book

didn’t.

Well, this crucified man starts having His side poked by a Roman centurion, and all sorts of blood and water are gushing out, and you could see His guts and He’s not moving or saying a word, so I decide—

Book

or no

Book

—I’d better take a look for His soul. But when I checked, it wasn’t there. I looked all over, in His spleen, gall bladder, kidneys, appendix, but this guy was as empty as the Darkness.

I looked around the foot of the cross in case it had dropped out, and even retraced His steps just to make sure it hadn’t escaped along the way, but not a thing. Now listen. I’m no soft touch. I’ve dealt with beggars and babies, the weak and the infirm. People have pleaded with me, offered me all manner of bribes—gold, jewels, erotic pottery—to get them off the hook. I’ve heard it all before, but I don’t make exceptions. Admittedly with Maud I bent a few rules, but I never let her live. There was an unspoken agreement between us that that was impossible, and although I had been growing increasingly remorseful at sending her into the Darkness, I never dreamed of

not

doing it. At least not then.

So I stood and scratched my head for a bit as the man’s family and friends took Him down from the cross. First He doesn’t appear in the

Book.

Then He hasn’t got a soul. It was unbelievable. Where had He come from? What was He doing here? Millions of years had gone by and every soul—even the pesky dinosaur souls—had eventually been accounted for. And now some soulless John Doe was about to screw the whole thing up. I looked at Him ruefully as His head was being covered in a shroud and, just for a second, I could have sworn He winked at me! But no, I thought, I must have been seeing things. I looked again and the body seemed still now. Bodies without souls don’t wink, I told myself. Then again, bodies should be in the

Book.

I had to get to the bottom of this.

Golgotha,

A.D

. 33: The (Cruci)fix Was In.

I started off with the usual suspects: the witch doctors, the soothsayers, the desert prophets, the hoodoo bone-men. Occasionally they’d accidentally say the right words in the right order and a certain soul would become sticky, or slippery, and I’d be fumbling with it all over the place. Creation, you have to remember, was somewhat imperfect; update had been added to update, patch added to patch. It wasn’t too hard to hack into it with some pretty basic magic.