Death and the Arrow (10 page)

THE CONDEMNED HOLD

Tonsahoten stood trial for murder at the Old Bailey at the next sessions. Leech’s mother brought the prosecution. The place was packed, despite the rain bucketing down on the crowd outside the Sessions House. The judge and jury sat under shelter, but the area for family, friends, enemies, witnesses, thief-catchers, journalists, and other assorted courtroom hangers-on was open to the elements. The judges wanted to avoid close confinement with the stench and lice of the disease-ridden criminals—and the disease-ridden public.

Tom, Ocean, and Dr. Harker all attended, and Tom recognized several customers from The Quill. Under-marshal Hitchin was there too, smirking with satisfaction. And Tom noted with a special disgust that the sinister Dr. Cornelius had also come to watch.

The outcome of the trial was never in doubt. The Mohawk remained silent throughout and did not react when the jury pronounced him guilty, nor when the judge condemned him to be hanged from the Tyburn gallows.

The crowd, on the other hand, cheered as if at a pantomime, delighted by the prospect of seeing this savage swing at the next Hanging Fair. They shouted and jeered and waved their hats while Tonsahoten was taken back to Newgate.

Dr. Harker led Ocean and Tom to The Quill and the three of them sat in melancholy silence for some time. Eventually, the doctor commented that though Tonsahoten was guilty of the murders and so by the law was justly condemned, he could see no evil in the man. Tom and Ocean agreed.

“I think he is a good man driven to bad deeds,” Dr. Harker added.

“And he won’t be the first of those to feel the noose,” said Ocean. “Nor the last, neither.”

Tom went to visit the Mohawk the following day. He dropped his money in the turnkey’s filthy palm, but the man blocked his way with his other arm. “Another shilling if you wants to see the savage,” he said. His breath stank of gin and tobacco. “He’s very popular, that one. We likes our freaks, we do. Good for business.”

It was pointless to argue. Tom dug another shilling out of his pocket. It was just as well that Dr. Harker had given him some money to take with him. Visiting Newgate was becoming an expensive business.

As Tom walked through into the Common Ward, there was more of a commotion than usual. The door to the Condemned Hold stood wide open and, looking in, Tom saw that it was empty. Then he saw Tonsahoten, towering above a crowd of shouting inmates, turnkeys, and assorted visitors. He pushed his way through the crowd and saw that in the center of it was a cleared space, and in the center of that was the Mohawk, chained hand and foot. He was stripped to the waist and Tom could see that the tattoos on his face continued down over his whole body.

The crowd had the look of madmen about them; they yelled and jostled for a better position, gap-toothed mouths in wine-red faces bellowing and jabbering. The din was hellish. Only the Mohawk was calm.

“Come on, Foster, where’s your man?” shouted one of the turnkeys. The crowd on the opposite side parted and an excited murmur ran round at the entry of another man, every bit as big as Tonsahoten and likewise both stripped to the waist and chained hand and foot. He had a gold ring in each ear and his head was smooth-shaven. Tom was beginning to realize what was going on.

“Come on, gentlemen,” cried the turnkey. “Place your bets, place your bets. We have here a savage from the Americas up against this seafaring giant. Place your bets, gentlemen, on these fine gladiators. You’ll not see a better fight than this in all of London!”

The two chained men looked at each other, both totally impassive, neither acknowledging the baying crowd around them. The men’s size and bearing had the effect of making the others look like children.

“Very well, gentlemen,” said the turnkey. “I won’t trouble these two warriors with petty rules. Rules is for lords and earls and other like fops. So, when I drops my hand, one man will set about the other until one falls insensible to the floor. The man left standing at the end is the winner.”

The crowd pulled back to make room and to avoid becoming entangled in the fight. The turnkey dropped his hand and the sailor took a couple of steps toward the Mohawk, who continued to stare straight ahead.

The sailor looked suspiciously at Tonsahoten and then punched him on the side of the jaw. It was a blow that would have downed a horse, but the Mohawk shook his head and looked at the sailor. The sailor hit him again, harder this time. Tonsahoten was forced to take a step back. The crowd grumbled. This was no kind of fight. The sailor looked about him and then squinted back at the Mohawk, trying to work out if this was some sort of ruse. “Why won’t you fight?” he asked. “You can take a punch well enough. Are you a coward or a Quaker?”

“I have no argument with you,” said Tonsahoten calmly.

The sailor snorted and hit him again.

“They call you a seafaring man,” said Tonsahoten.

“What of it?” said the sailor, amazed that the Mohawk was still on his feet.

“I too know something of the sea.”

“I daresay you do,” said the sailor. “I hardly thought you flew across the ocean.” The men round the sailor laughed. “Now put up your hands, Indian, and fight like a man.” But Tonsahoten did not move, and again the sailor hesitated.

“Come on!” shouted one of the men nearby. “Get on with it! Kill him!”

“Put up your hands, savage,” said the sailor again.

“I will not,” said Tonsahoten. “We are not chained bears to fight for their sport. We are free men.”

The sailor laughed. “You don’t look too free,” he said. “And I don’t feel it, neither.”

“We are free men in chains,” said Tonsahoten. “That is all. Look about you, mariner. Will a man like you fight on the say-so of men like these?” The sailor looked about him at the filthy, jeering crowd as if seeing them for the first time, then back at the Mohawk. “Let us not shame ourselves for these bilge rats,” Tonsahoten continued. “We could have been shipmates once. Maybe we will still?”

The sailor smiled. “Aye,” he said. “Maybe we will at that. In any case, I’m not sure I could hit you any harder without breaking my fist.” He lowered his hands.

The crowd exploded with anger. Foster, the inmate who had brought the sailor to the fight, cursed and berated his protégé, until finally the big man cuffed him on the side of the head, knocking him to the floor, unconscious. “Lord, how I miss the sea!” said the sailor, closing his eyes and shaking his head. “Peace be with you,” he said, turning back to Tonsahoten.

“And with you,” replied the Mohawk.

“Come on, come on,” said the turnkey, jabbing Tonsahoten in the side with a pikestaff. “If you ain’t gonna fight, you can get back in the hold.” Other turnkeys dispersed the crowd.

As the Mohawk was being led back to the Condemned Hold, the Reverend Purney blocked his path. He had already tried several times to extract Tonsahoten’s confession. It would make a bestseller—he was sure of it. “I must have words with you, savage,” he said. “Even though you are a heathen, you may yet save your soul, in the love of Our Lord Jesus Christ, if you repent of your sins and accept the one true God.”

“I have a god,” said Tonsahoten. “I do not need another.”

“There is only one God,” said Purney. “You must give up your heathen gods.”

“You take my land, and now you try to take my god?” said the Mohawk angrily.

Purney backed off nervously and tripped, falling onto the pig, which squealed under his weight. The one-eyed dog lurched forward and made off with the reverend’s wig in its jaws. Purney got to his feet and ran off in pursuit of the dog as the whole room erupted in laughter.

The turnkey was still laughing as he pushed the Mohawk into the Condemned Hold. Tom ran over to the door just as the turnkey was locking it. “I’ve come to see the Mohawk,” he said.

The turnkey shoved him away. “No visitors,” he said.

“But—”

“No visitors!”

yelled the turnkey, pointing the pikestaff at Tom.

Tom sighed and sadly made his way home.

Two days later, Tom approached the prison once again in the hopes of seeing his friend. Just as he was joining the line of visitors, a voice made him turn in panic.

“Well, well,” it said. “If it isn’t my young friend.” It was Shepton. Tom backed off toward the crowd.

“Don’t worry,” said Shepton. “I am not going to harm you—though I should, for what you did to Fisher. No, I am away to pastures new. Tell the savage that his actions have only served to make me even richer, for now all the remaining silver is mine, with none left to share it with. Thank him for me. Tell him that I wish I could see him hanged but I sail on tomorrow’s tide.” With that, he tipped his hat, grinned, and walked away.

This time the turnkey would only let Tom whisper to the Mohawk through the grille of the door to the Condemned Hold. He could barely see Tonsahoten in the gloom, but when he told him about Shepton, he heard the links of his chains scrape together and a low groan like that of an injured bear.

The next morning, as Tom was trimming leaflets in the workshop with his father, the door burst open and Ocean almost fell in, panting for breath.

“Tom . . . Mr. Marlowe . . . Begging your pardon ...It’s—”

“What?” said Tom. “Has something happened?”

“He... he... he’s escaped!”

FROST FAIR

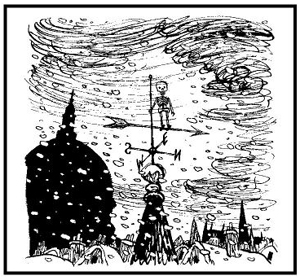

London buzzed like a beehive when it heard the news of the Mohawk’s escape. He had broken free of his chains in the night and overpowered the turnkey who came to check on him. Wearing the turnkey’s hat and wig, he had climbed the stairs leading onto the roof, leaped across to a nearby chimney stack, and made off.

Ballads were sung, and there was even a harlequinade called

The Cunning Savage

performed at the Drury Lane Theatre in Covent Garden. In this production, an actor with painted tattoos and holding a bow and arrow sang a song entitled, “I was only a humble Savage, but now I’m the Talk of the Town.” Fashion-conscious fops took to wearing silk quivers over their shoulders filled with silver-tipped arrows with peacock-feather flights. Women wore the most ridiculous-looking feathered headdresses and pinned bow-and-arrow brooches to their gowns.

The antics of the Mohocks had ceased to divert the newspaper-reading public. How could they compete with a real savage, a real Mohawk? True, some young rakes tried their hands at archery until a handful of ugly accidents forced the city to ban bows and arrows completely. But in any case, London soon became bored with Indians, arrows, and the like.

Tom was glad that Tonsahoten had gotten away; he was relieved to see his hanging day come and go, with the hangman cheated. Dr. Harker too seemed happy with how things had turned out. Ocean drank to the Mohawk’s health and wished him well. All three hoped he would return to his life at sea and forget about Shepton.

A friend of Ocean’s had confirmed that Shepton had indeed left London, buying passage for himself on a ship bound for Alexandria. He had evaded justice for Will’s murder, but Tom was just glad that he was now half a world away.

And so, gradually, Tom’s life returned to its old pattern, though there was one welcome change. Ocean began working in the print shop. The Lamb and Lion had never been busier and Tom and his father welcomed the extra set of hands. For his part, Ocean was grateful for the trust they put in him.

The summer of 1715 was hardly any summer at all. Tom braved rainstorm after rainstorm to see that there were always fresh flowers on Will’s grave. The city streets were filled with filthy puddles, while the gutters became small rivers, carrying their stinking flotsam downstream to the Fleet ditch and that sewer of all sewers, the Thames itself.

Winter, when it came, was as sharp as an ax. A bitter wind gnawed at the city and those who could afford it piled the hearth high with sea coal, fresh off the colliers down from the Tyne. Those who could not afford it did the best they could—or died. The smoke from the sea coal blackened the London sky even more. And not just the sky: the houses, the shops, even the horses and the good people of London themselves were covered in the soot that fell from the foul-smelling smog.

Ice formed on the rancid waters of the Fleet ditch as snow fell on the dome of St. Paul’s. Horses fought to keep their footing on the frozen cobbles and Londoners slipped and slid their way from home to coffee house, from marketplace to theater. Slowly, as the nights grew ever colder, ice began to spread out from the banks of the Thames, blue-gray above the waters of the river. Watermen found it harder to get from shore to shore. Even the rushing dam between the arches of London Bridge slowly turned to ice. The river was frozen over.

The watermen were furious, their livelihood gone. What use was a ferryman now that a person could walk from Charing Cross to Southwark? But for Tom, and most of the rest of London, the freezing of the Thames was a cause for celebration, because it meant there could be a Frost Fair!

Tom came on the first night to help his father set up a stall selling commemorative posters and prints. It was an amazing sight. Striped tents crowded the ice, with multicolored flags and bunting flapping in the breeze. There was a man juggling flaming torches, a woman walking a tightrope; there were beer tents and pie stalls, puppet shows and music; goldsmiths and silversmiths showed their wares. People of every kind and class, dressed in silk or dressed in rags, all marveled at the scene.

The prints on Mr. Marlowe’s stall were selling like hotcakes. Ocean had agreed to help Tom’s father and proved to be a natural salesman. In fact, he was doing so well that Mr. Marlowe had to ask Tom to return to the print shop and collect some more stock.

Tom was reluctant to tear himself away from the fair, but Fleet Street was not far away. He would be back in no time. He set off across the ice and up some steps leading to the Strand. He was almost at the top when someone grabbed him from behind.

“Where is he, boy?” hissed his attacker.

“Who? What do you want? I have no money—”

“The savage. The Mohawk. Where is he?” As the man asked the question, he spun Tom round and showed his scarred and evil face.

“Shepton!” said Tom.

“You have not forgotten me, then?” said Shepton. “Or what I am?”

“No!” shouted Tom. “You are a murderer!”

“Then know that I will not hesitate to end your puny life if you do not straightaway tell me of the whereabouts of that savage.”

“I don’t know,” said Tom. “How could I? He is long gone.”

“Gone from you, maybe,” said Shepton, “but not from me. I have traveled the world, and everywhere I turn he follows me, like some sort of devil. Wherever I go, among Turks or Spaniards, Chinamen or Arabs, there he is. He has dogged my every step these past months, trailing me round the globe.” His face contorted into a sneer. “But as you see, he has not done me in, for all his efforts, and I will kill him yet. Where is he, boy?”

“I swear that I do not know,” said Tom.

“Then you are of no use to me, are you, boy? Farewell.” Shepton put his hands to Tom’s throat and began to squeeze. Tom’s struggles were of no use and quickly began to fade.

“Leave the boy alone!”

Shepton loosened his grip on Tom, who collapsed to the ground, and turned to see who had shouted. He let out a contemptuous laugh as he saw Dr. Harker standing a few yards distant. “You?” he shouted. “You dare to challenge me?”

“I have a sword!”

Shepton laughed again and, pulling his own sword from its scabbard, walked toward the doctor. “Then draw it and use it!” he said.