Death from a Top Hat (26 page)

Read Death from a Top Hat Online

Authors: Clayton Rawson

Gavigan eyed the card, frowning, and Merlini explained: “That’s the trick in which a chosen card is shuffled back into the deck and the deck thrown against the ceiling. The cards fall in a shower, but the selected card remains sticking there. I’ll show you sometime.”

Several red and green silk handkerchiefs and two or three steel hoops from a set of Linking Rings lay in one chair. On the floor near the bedroom door I saw a dress tie. And inside we found the dress clothes strewn about on the floor and on the bed. The monocle lay on the dresser.

“Everything’s been left just as it was found,” Gavigan explained.

Under my watchful eye, Gavigan and Merlini nosed about as if engaged in a game of Hunt the Thimble. The Inspector began investigating the contents of a desk in the living room. Merlini’s survey seemed aimless, but his quick eyes darted about, probing, scrutinizing. Finally he strolled into the bathroom and I followed. The towel with the make-up on it lay on the floor. Merlini examined it intently, then walked to the medicine cabinet and opened it. He regarded the contents briefly, started to close the door, and stopped.

“That’s odd,” he said. He looked for a moment longer and then examined the ledge of the wash basin, which held a bar of soap and a tube of toothpaste without a cap. He got down on his knees and made a hasty but thorough search of the floor. He got up, a pucker between his brows, then silently turned and walked out.

I opened the cabinet and took a look for myself. The contents consisted of shaving brush, shaving cream, a safety razor, a box of blades, several used blades lying loose, a box of aspirin, a bottle of shampoo, a mouth wash, Witch Hazel, a packet of flesh-colored sticking plaster, Mercurochrome, a jar of cold cream, and the stubby end of a styptic pencil. A toothbrush hung in a holder affixed to the inside of the cabinet door.

I didn’t see anything particularly odd in that collection. Except for the cold cream, I had all those things in my own cabinet at home.

I went after Merlini and found him in the bedroom, busily going through the drawers of Tarot’s dresser. Whatever it was he was looking for, I gathered from his expression that he was unsuccessful. He had just finished and was scowling thoughtfully at himself in the mirror when Gavigan let out a surprised snort that carried clear from the other room.

“Listen to this,” he said as we came in. He held a bankbook and read from it, “May 27, 1935, $50,000.”

“Hmmm,” Merlini said, “Sabbat deposits $50,000 and on the same day Tarot withdrew fifty—”

“No,” Gavigan said excitedly, “He didn’t withdraw it. It’s a deposit.”

“What!”

“You heard me. I suppose there could be two people in New York City who would each deposit an even $50,000 on any one day, but if this deposit was made in cash too, then—”

“The chances of its being a coincidence aren’t much,” Merlini finished.

“And,” Gavigan added, “the chances that it’s blackmail are good.”

“Obviously,” Merlini said. “But how do we connect that with the murders? None of our suspects are in any position to pay a blackmailer, or a couple of blackmailers, $100,000. Watrous is probably the wealthiest, and I’m sure that amount would have cleaned him out. What about the other entries? Tarot wasn’t stony like Sabbat, was he? According to Variety he’s been collecting almost a grand a week lately, with his radio acting and writing and his Rainbow Room engagement.”

“No, he’s pretty well fixed, though not as well as he should be. He’s evidently dropped a good bit on the market. There are a flock of checks made out to Kneerim & Belding, Brokers. But he’s still a few thousand ahead of the game.”

The Inspector picked up the phone and dialed. Sabbat’s number. He flicker through the pages of the bankbook interestedly as he waited.

“Parker, this is Gavigan. Have you found any explanation of that fifty grand yet?…Well, keep at it. It gets queerer by the minute…You what? Who’s the beneficiary?…Mrs. Josef Vanek! Who the hell’s she?” Gavigan listened, and I gathered from his attitude that Parker had not been idle. Finally he told Parker to report to headquarters and have them get on it. Then he hung up and said, “Did you ever hear of Joseph Vanek and wife?”

Merlini shook his head. “I haven’t had the pleasure. What did Parker find, a will?”

“No, a life insurance policy for $75,000. And Josef Vanek’s handwriting, according to Parker, is identical with Sabbat’s. What do you think of that?”

“Looks as if it might be a reason why no one seems to have heard of the man during his ten-year absence.”

“Exactly. And when we locate Mrs. Vanek, maybe we’ll turn up something in the way of a motive.”

Gavigan gathered up the check-and bankbooks, and we left the apartment. In the elevator he asked, “And did you find what you were looking for, Merlini?”

“No,” Merlini answered, scowling at the back of the elevator operator’s neck. “But what’s worse, I didn’t find something I wasn’t looking for.”

“All right, Hawkshaw,” Gavigan said, “but you won’t convince me you’re not an amateur detective until you stop trying to be cryptic.”

“

Trying

to be cryptic?” Merlini said. “It is cryptic. So much so that I can see only one explanation, and that’s utterly fantastic.”

“I can believe that. If

you

think it’s fantastic, it certainly must be. You can have it.”

Dead End

I

T IS ALMOST AXIOMATIC

that great detectives are fastidious gourmets. Merlini, when he selected his Smorgasbord, flew straight in the fact of tradition. He merely started at the nearest end of the table and worked around it to the left, gathering the hors d’oeuvres as he came to them with all the dainty discrimination of an automaton. Inspector Gavigan did no better, differing from Merlini only in preferring a counterclockwise route.

They brought their heaping plates back to our table and began pecking at the food abstractedly. Before long Gavigan gave up even this pretence, and with his fork began drawing on the tablecloth a complex, interlocking design of squares and circles. After a bit he spoke, as much to himself as anyone else.

“If we do find a talking machine,” he mused, “it would seem to let Jones out. He’d naturally be somewhere other than in front of that door when the thing began spouting. And yet, except for Duvallo, he had the best chance to set any such an arrangement. He lived there for some weeks, and he had a key to the house. Of course, one of the others might have had a duplicate made—” He grabbed at a passing waiter. “Where’s the phone in this place?” he demanded.

As Gavigan bustled off, Merlini abstractedly began building a tower of sugar cubes, using a card house structure. It was five high when the Inspector came back and sat down grumpily. The sugar edifice toppled and collapsed.

“I just had Malloy examine the lock on Duvallo’s front door,” Gavigan announced. “He found paraffin traces.” He scowled at his water glass. “Someone coated a blank with paraffin, put it in the keyhole, and turned it so that it touched the lock mechanism. The marks left by the points of contact served as a guide for filing the key to the proper shape.”

Merlini shook his head slightly as if to straighten out his thoughts. “Now,” he said, “that’s positively illuminating.”

“In other words, you don’t know what the hell it means. Neither do I. It certainly doesn’t help eliminate anyone, except maybe Duvallo and Jones, who, having keys, wouldn’t need to make one.”

“And our friend Surgat, who, though not having one, wouldn’t need one anyway.”

“Merlini, you know these people. Which of them could have a motive for both murders?” asked the Inspector thoughtfully.

“Well, Jones and Rappourt disclaim knowing Sabbat, while Watrous and Rappourt say they hadn’t previously met Tarot. Of the others, only the LaClaires have an obvious motive for killing Sabbat. I’m not

au courant

enough with Zelma’s sex life to know if Tarot figured in it too, but I wouldn’t say it was impossible.”

“Tarot,” Gavigan said, “acted as if he had it in for Duvallo, and if that’s true the reverse is likely. Ching knew Sabbat better than the others and thus could have had more opportunity for acquiring a motive. Judy—”

“Yes?” Merlini prompted.

“Well, sex could rear its lovely head there. Sabbat might have made lecherous motions, and since she worked for Tarot—umm, he might have—”

“You have a lewd mind, Inspector. He might have been blackmailing her because she’s the comely leader of a gang of dope runners, while Ching, a member of the Baluchistan Secret Service, is trying to steal from Greenland’s high command the blueprints of a collapsible submarine which Tarot had snitched from Sabbat, and was carrying sewn into the lining of his underpants. Now go on with the story.”

“Say,” I wanted to know, “who’s writing this yarn, Oppenheim?”

Gavigan said, “He doesn’t think a discussion of motive is going to help. It won’t, the way it’s being discussed.”

“Do we have to have murder with our meals?” Merlini asked as he took out a pencil and began drawing on the tablecloth an odd geometrical diagram only slightly more sensible than Gavigan’s aimless cross hatching. He started guiltily when the waiter, arriving with the soup, gave his draftsmanship a cold Swedish stare. He covered his embarrassment by reaching for a roll, breaking it open, and shaking from its center a shiny half dollar. I was one up on the waiter, who retired uncertainly as Merlini reached for more rolls; I recognized the coin.

Gavigan, whose realistic soul disliked the unsettling effect of Merlini’s small miracles, ignored the incident and pointed with his spoon.

“What’s that diagram? I suppose it’s too much to except that X marks the spot where we find the phonograph?”

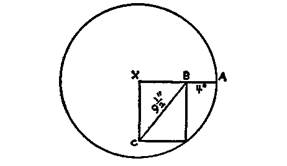

The design had this appearance:

“X,” Merlini announced, “is the center of the circle; BC is 9½ inches long, and BA is 4 inches. What’s the diameter of the circle? No calculus required. Nothing but common ordinary sense. Par for the course is one minute flat.” Merlini added a psychological handicap by glancing at his watch, and then began on his soup.

I eyed the diagram suspiciously and hazarded, “The square of the hypotenuse of a right angled triangle is equal to the sum of the squares of the other two—”

“That’s it,” Gavigan said. “Nine and one half squared minus the square of—of—” He bogged down. “No. We can’t solve a triangle with only one side and one angle given. We’ve got to know the length of XC in order to find XB.”

“Not this time you don’t,” Merlini grinned.

The Inspector glared at the diagram and I helped him without result, until finally Merlini said, “Time’s up. Go to the foot of the class, both of you. Misdirection wins again. That’s my favorite brain teaser because it’s a perfect diagrammatic example of misdirection. The answer is right in front of you all the time. I asked for the diameter and I gave you the radius. You can multiply by two, can’t you?”

“You gave us—” I started and then we both saw it.

Merlini continued, “The two diagonals of a rectangle are equal, anybody knows that, and I told you that one of them measured 9½ inches; the other, the undrawn one, is the radius. Twice 9½ is nineteen. Q.E.D. The answer stares you in the face, and you don’t see it because that superfluous four-inch red herring neatly misdirects your attention and leads your reasoning up a blind alley to a dead end. You vanish handkerchiefs and watches the same way; focus the audience’s attention on the right hand and they completely fail to see the nefarious operations in which your left is—”

“That’s how our murderer vanished, I suppose,” Gavigan said with some sarcasm.

“Sure, why not? When you meet an impossibility, it only means that there’s been some faulty observation or some bad logic somewhere—either that, or the science of physics is haywire and Surgat and his infernal friends do exist. And note that faulty observation. It’s the more important. A whole audience of impeccable logicians can be fooled if their observation is properly misdirected. I might cite the case of Gavigan and Harte and the Puzzle of the Circle’s Diameter. Misdirection, then, is the first fundamental principle of deception. The other two—and they are all used by magicians, criminals, and detective story authors alike—are Imitation and Concealment. Understand how those principles operate, and you should be able to solve any trick, crime, or detective story. It’s only necessary—”

“Careful, Merlini,” Gavigan warned, “or you’ll have to back that up by delivering some high, wide, and fancy deducing. And if you don’t pull it off—”

“It won’t be the fault of the method; it’ll be because I haven’t applied it properly. That’s just the trouble. There are a lot of nice deductions in this case, but they don’t all come out together.”

“I’ve noticed that,” Gavigan said acidly. “I thought you didn’t want to discuss murder while you ate.”

Merlini looked at his now cold soup ruefully. “I don’t seem to be eating, and I wasn’t talking about murder. I was explaining the principles of deception to a very inappreciative Inspector of Police.”

“Be good, you two,” I broke in. “If I’m going to write up this case I’d like a little harmony between the forces of law and order.”