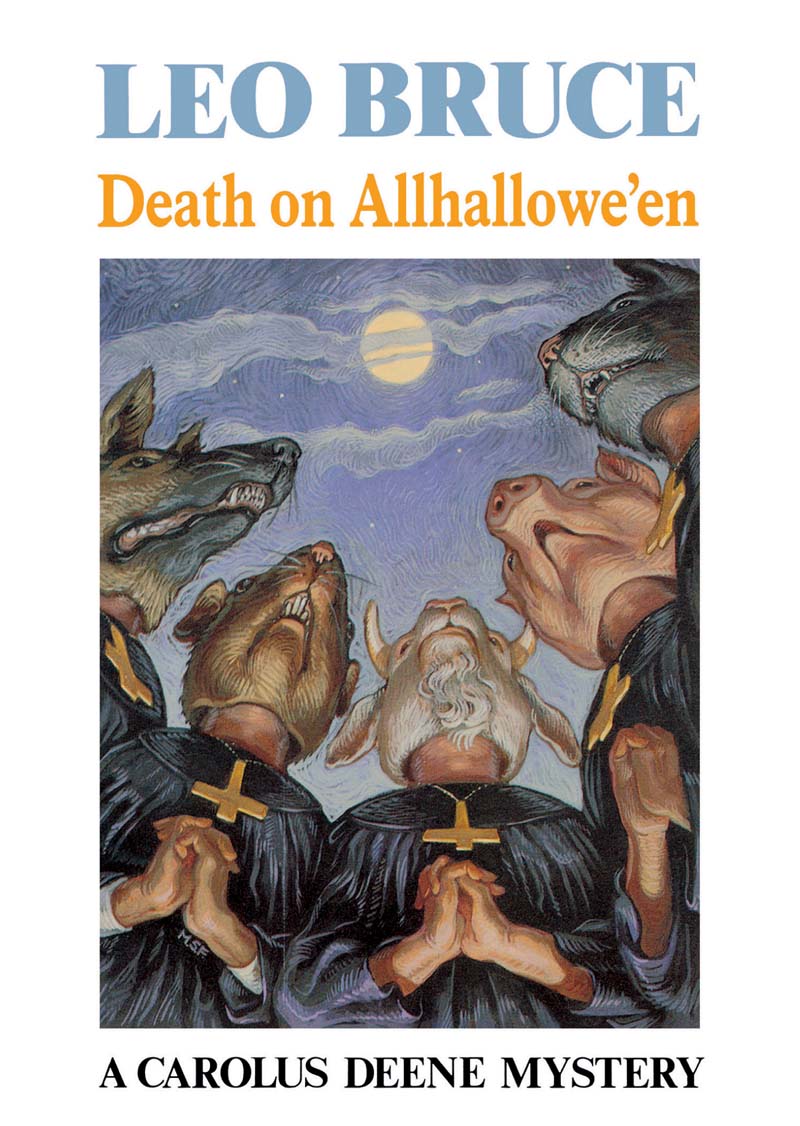

Death on Allhallowe’en

Read Death on Allhallowe’en Online

Authors: Leo Bruce

DEATH ON ALLHALLOWE'EN

Carolus Deene, the amateur detective with his own style of solving riddles of violent death, has to bide his time in the small Kentish village of Clibburn, where he is early given to understand he is a âforeigner'. However, despite a trick to have him elsewhere, he is present when a popular local figure is shot dead on the stroke of midnight, and before his work is completed he has the answers to two other deaths, one of which was not even suspected. While he is not sure how seriously to take the local witchcraft stories, he perceives how a past event can have provided a blackmailer with a rare opportunityâand from that moment his own life is in danger.

“SERGEANT BEEF” NOVELS:

Case for Three Detectives

Case without a Corpse

Case with No Conclusion

Case with Four Clowns

Case with Ropes and Rings

Case for Sergeant Beef

Cold Blood

At Death's Door

Death of Cold

Death for a Ducat

Dead Man's Shoes

A Louse for the Hangman

Our Jubilee is Death

Jack on the Gallows Tree

Furious Old Women

A Bone and a Hank of Hair

Die All, Die Merrily

Nothing Like Blood

Such is Death

Death in Albert Park

Death at Hallows End

Death on the Black Sands

Death at St. Asprey's School

Death of a Commuter

Death on Romney Marsh

Death with Blue Ribbon

Published in 1988 by

Academy Chicago Publishers

425 North Michigan Avenue

Chicago, Illinois 60611

Copyright© 1970 by Leo Bruce

Printed and bound in the USA

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the express written permission of the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bruce, Leo, 1903-1980.

Death on allhallowe'en.

I. Title.

PR6005.R673D44 1988 823â².912 87-35 173

ISBN 0-89733-293-8

ISBN 0-89733-292-X (pbk.)

âI tell you candidlyâI'm frightened.'

Carolus Deene looked at the speaker incredulously. He had known him for almost thirty years, since they had shared certain experiences at Arnhem, and the recollection of these made him smile at John Stainer's confession.

âYou?'

âYes. I. Me. Whichever it is.'

âScared by an old woman playing at witchcraft? I don't believe it.'

âIt's not just that. I was as sceptical as you are at first. You had better let me tell you the whole story and then see whether you want to laugh it off.'

âGo ahead,' said Carolus. âI'll keep an open mind. Perhaps I had better tell you first that I do believe in the devil. Yes, Satan, the Prince of Darkness. I believe he is at work in the world of today, seeking whom he may devour. And I don't think that calling him Old Nick or Old Harry and talking about his cloven hooves and generally being joky about him makes him any less credible. But I

don't

believe he comes in person to the call of some old fortune-telling crone who does things with wax and hot needles.'

âNor do I. It was foolish of me to tell you that first.'

John Stainer was the rector of a country parish and although he did not wear a clerical collar or talk sermonese or behave as a painfully hearty good mixer, it was not difficult to guess his calling. Thick white hair and a young face gave him a

frank and easy expression and one could see why he had always been a popular man.

He nodded to Carolus who was offering him a whisky and soda, and went on, âI should have started with the village and broken down your disbelief by telling you something about that. It's called Clibburn â¦'

âOh, is it?' interrupted Carolus. âThen you have your hoof-mark right away. You need look no farther then the

Concise Oxford Dictionary. Klioban,

Old High German for “cloven”. But I'm no etymologist and that may be nonsense.'

âDo you know anything about the Isle of Guys?'

âOnly as a geographical fact. It's in the Thames Estuary, isn't it?'

âYes. Or thereabouts. Like the Isle of Sheppey and the Isle of Grain. They're peninsulas really. Guys consists of about ten square miles of grazing country, one large village, two groups of cottages, one church, two pubs and a population of about a thousand people. It has not yet been discovered.'

âYou mean exploited, surely?'

âI mean discovered. Guys is one of those tracts of country, of which there are more in Great Britain than you imagine, which almost nobody visits and in which absolutely nobody would choose to live. It is flat and dreary with rain and mists coming in from the estuary and mudflats instead of a beach. Obviously it has the usual amenitiesâtelevision, radio, electricity, mains waterâbut only one road connects it with the Kentish mainland and that is sometimes flooded. The inhabitantsâand this is perhaps the pointâcall themselves Guysmen, and are mostly the sons of Guysmen for a good many generations. The names on the gravestones show that.'

âA perfect setting for the goings-on you describe. Too perfect. I find it hard to believe in the Isle of Guys.'

âSo did I, at first. In fact, when I was given the living nearly three years ago and went to live in the very comfortable modernised rectory. I thought the whole place was almost cosy. You don't see anything odd at first. Young people With

It, swinging, whatever the term is at the moment. Older people bridge-playing, viewing television, having a drink at the pub, all like any other village. Perhaps rather more church-going than most.'

âOf course. People who believe in the devil must surely believe in God.'

John Stainer ignored this.

âAll quite normal, in fact. Then you begin to notice things.'

âWhat sort of things?'

âI can't just reel them off. I can't even distinguish between what may be significant and what I imagine to be. But for one thing the extraordinary attention paid to the woman I told you about, Alice Murrain.'

âTell me more about her, for a start.'

âShe's about fifty. A Guyswoman, the daughter of a farmer who committed suicide thirty years ago.'

âHow?'

âHanged himself, I believe. Alice's mother died in giving birth to her. People still talk of the surprise that was felt when Alice went away after her father's death and returned with a husband, a complete stranger to Guys who has never succeeded in integrating himself in the life of the place. I find him very difficult to get on with, a lean, shifty sort of fellow who smiles a lot but says very little. He seems to have a life of his own and goes up to London quite often without his wife. But he is a mere consort. Alice Murrain is a sort of queen.'

âOf spades?'

âCarolus, I don't like listening to gossip, and what I have heard comes chiefly from people who don't live in Clibburn. She is said to have the Evil Eye, with all the powers that go with it. She is also supposed to have Second Sight.'

âQuite an oculist.'

âI know it must all seem rather absurd to you. But you haven't lived in the place.'

âIt doesn't sound absurd. I know what superstition can do to people. Haven't you anything more cogent?'

'Yes. I have. Xavier Matchlow.'

âA Catholic, presumably?'

âRC? Certainly not now, though he may have been christened one. He was for many years a disciple of Aleister Crowley.'

Carolus laughed aloud.

âThat old bogyman!'

âI quite agree. In himself. But there is no doubt of the effect he had on others. He was a fraud and a charlatan but people believed in him. The lives he ruined are a matter of history.'

âAnd Matchlow's was one of them?'

âIt is hard to say. He is a rich recluse.'

âNoctambule?' asked Carolus mischievously.

âWell, yes. He walks at night.'

âMoonlight?'

âAll right, Carolus. You can send me up. But wait till I have told you everything.'

âYour friend Xavier is presumably a bachelor?'

âNo. Mrs Matchlow is one of the few friends I've got in Clibburn. Very down-to-earthâa thoroughly nice woman. I once gently approached the subject of her husband's former friendship with Aleister Crowley and she dismissed it at once. “I've no patience with that sort of thing,” she said.'

âYou say her husband is a rich recluse. What do you mean by that?'

âHe is a very rich manâowns a lot of land round Clibburn. He goes shooting, his only sport. Otherwise he never goes anywhere, so far as I can tell. Judith his wife has a car but he's never seen in it. His only acquaintance seems to be a farmer named William Garries who lives about a mile out of the village.'

âWhat do you know about him?'

âRather a nineteenth-century figure. Big fellow, sixtyish, hard-working and hard-drinking. Has one son, George, who seems a very ordinary, quite pleasant young man. The farm has been in the Garries family for centuries, I believe. Father

and son come to church, but there are stories about them.'

âStories?'

âThe usual thing. Witchcraft. Black magic.'

âDo you believe them?'

âNot really. I certainly shouldn't have done so three years ago. It may well be that the place is getting on my nerves. But there was one small incident some months back which made me wonder. I was passing the church rather late one night and saw a light on. I was going to investigate when it was extinguished. As I reached the wych-gate I met William Garries leaving the churchyard. He was not drunk, but I fancied he had been drinking. He smiled and said good night quite cheerily and was going to pass when I stopped him and said, “Did you see a light in the church, Mr Garries?” “Light? No,” he said, and walked on. I found the church locked, but everyone knows where the key is kept under a stone near the porch. Next morning, when I went over as usual at seven-thirty, I noticed something very disturbing and unpleasant. There is a crucifix hanging behind the pulpit, a recent gift to the church from a parishioner. It had been hung upside down.'

âI don't like that,' said Carolus. âNothing else was touched?'

âNothing.'

âWho was the parishioner who gave you the crucifix?'

âA man named Connor Horseman. He came to live in the village a little before I did.'

âWhat significance do you attach to the inverted crucifix? Old-fashioned Anti-Christ?'

âYes, but a rather special form of it, I should think, else why was nothing done to the crucifix on the high altar? Or anything else in the church? No, I think this was aimed at me. No one else occupies the pulpitâunless on very rare occasions some visiting preacher. I stand beneath that crucifix every Sunday and hold forth.'

âCouldn't it have something to do with the man who

gave

the crucifix, though?'

'I suppose it could. The whole thing is so twisted. Sometimes I think these people are up to something really fiendish, devil-worship, the cult of Satan; sometimes I see nothing but antiquated and ignorant notions of witchcraft.'

âTell me about the donor of the crucifix.'

âCertainly. He's a writer. He is not popular with the older people, I believe, but then strangers seldom are. I'm not myself. But I rather like him. He is about our age. Lost a leg in the war.'

âYou're giving me a very concise who's who, John. Haven't you a village idiot to produce?'

John Stainer smiled.

âNot far from it. Charlie Sloman. He's a young man of twenty or so whose mental age is about fourteen. Perfectly well behaved and a rather engaging character, but very irresponsible. A practical-joke mentality.'