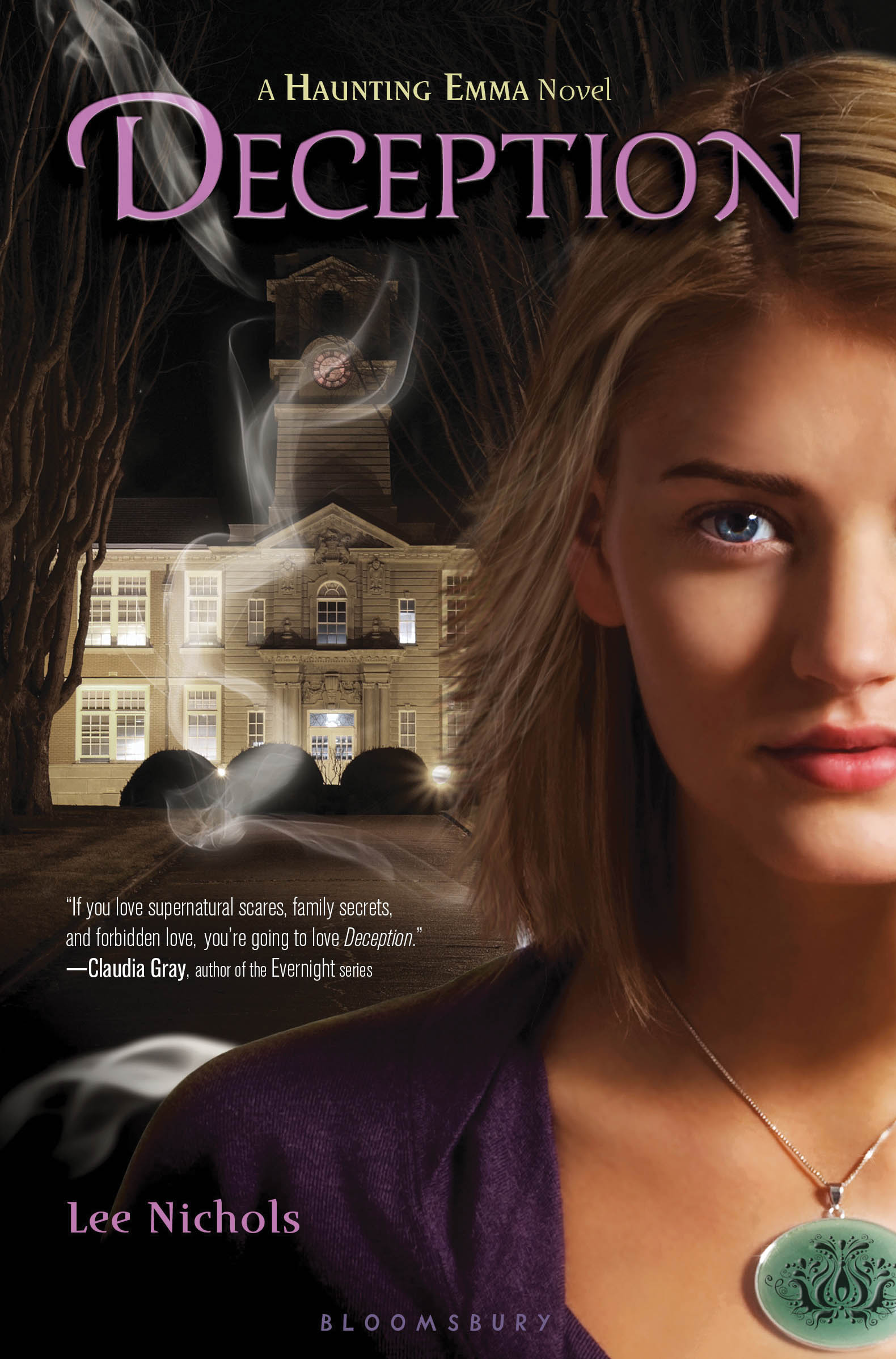

Deception

Authors: Lee Nichols

I couldn’t see, couldn’t breathe. Strapped to a chair underwater, I was shivering and my lungs burned. A moment before I blacked out, the chair rose through the icy darkness and broke the water’s surface.

I gasped and coughed, but the instant I caught my breath, he plunged me under again, brought to the verge of drowning over and over.

“Once more, Emma?” he asked. “Or will you answer me now?”

I longed to tell him everything, to end the fear and stop the pain. Then the chair plunged again into the freezing water.

Six weeks ago, my parents disappeared.

I’d left them at the San Francisco airport at seven in the evening, nervous and excited. These were their last words:

Dad: “There’s money in the bank; use your ATM card. If you get in trouble …” He looked at me. “Don’t get in trouble. We have our cell phone. You can call us anytime.”

Mom: “You know a scarf isn’t a jacket, Emma.”

It was a chilly forty-eight degrees

—

sometimes I wondered if San Francisco was really in California. I’d worn a black sweater, black jeans, black boots, and a red embroidered pashmina my parents brought back from one of their many business trips. The scarf was wound tightly around my neck and shoulders.

Me: “That’s really the last thing you’re going to say to me?”

Mom: “A hat helps, too.”

She fingered my short, choppy blond bob

—

a haircut she hadn’t approved

—

looking like she was about to say more, but she hugged me instead.

I suppose if I’d known they were going to vanish, I would’ve said “I love you” and “I’ll miss you.” Instead, I left them at the curb and sputtered home in our ancient Volvo wagon, already planning my fall from grace: clubbing until 4:00 a.m., unsupervised shopping sprees, and maybe even a tattoo if I could come up with something good.

Hoping for inspiration, I paced our mausoleum of a house. Seriously, our coffee table was a stone sarcophagus; it was like we snacked off Nefertiti’s head. My parents were overly fond of the dead, or at least the possessions of the dead. They sold antiquities from a store below our apartment on Fillmore Street, and the apartment was filled with relics and icons. Even the sofa was 150 years old

—

horsehair, dust mites, and all.

My family had owned the building for generations. I guess we were rich, despite the old car, my pathetic allowance, and public education. Why else would we have the high-tech security system for both the store and apartment, which required a thumbprint to get in? When we were younger, my brother, Max, and I pretended we were 007 agents. Now it was just an aggravation every time I left the house for a red-eye chai from the café next door.

You’re probably wondering what kind of parents leave their seventeen-year-old home alone for God knows how long. They’d said three weeks, but my parents didn’t always stick to the plan

—

this trip, in fact, was last minute. Still, I wasn’t completely alone. They had exactly one employee, Susan, who’d run the shop for the past ten years, and she was supposed to check on me every night.

Susan’s daughter, Abby, was my best friend

—

emphasis on

was

. Two years older than me and two years younger than my brother, we’d grown up together, hanging out after school, obsessing over guys and our mutual lack of nice fingernails. Abby and Max were always close; he even tutored her in French. And with our parents away so often, Susan became a surrogate mother to us.

Then, this summer, when Max was home from Harvard, I discovered him and Abby having The Affair.

I’d just gotten back from the café next door when I heard noises coming from Max’s room. I’d barged in without knocking and discovered them

—

which put a whole new spin on the French lessons.

It was more of Max’s skin than I’d seen since I was a toddler, but I’d blocked out a lot from my past; it was just one more image to add to the file. And they were both happier than I’d ever seen either of them. For two months, things were great.

Then Max dumped her.

Abby was devastated, and there was nothing I could do except keep the Kleenex and chocolate flowing. I have no idea how Max took the breakup, or why he ended it, because the next day he left for his junior year abroad.

Now he was in Tibet or Timbuktu, someplace he could only be reached by yak. Which was so Max

—

kind of cool, and kind of cold. Breaking hearts in California so he could bring safe drinking water to remote villages in Asia.

So I wasn’t completely alone, because I still had Susan. Except Abby blamed me for the breakup, or at least I thought she did. I didn’t really know because she hadn’t talked to me since she’d left for UC, Santa Barbara. And her mom was following suit.

While my parents thought me safe in Susan’s hands, she was acting like I was her daughter’s worst enemy. She definitely wouldn’t be checking up on me as much as she usually did. A girl could get into a lot of trouble with so much freedom. I couldn’t wait to get started.

But I wasn’t exactly sure how. Clubbing wasn’t the kind of thing you did alone, the shops were closed, and I was still debating the body art. So I lay alone in bed that night, with only my laptop for company. Instead of talking to actual humans, I messed around on Facebook. I caught up on how everyone was doing at college and stalked my current fixation, the painfully unobtainable Jared from school.

Then I e-mailed Max:

I imagine the yaks run on treadmills to create enough electricity for you to check your messages. Like a Buddhist episode of

The Flintstones.

Why did you dump Abby? You know you miss me.

—

Emma

My daily pleading senryu went to Abby. She never responded, but I was nothing if not tenacious:

My brother is a dickwad

While you rock Organic Chem

Talk to me?

Abby was doing premed at UCSB and worried about Organic Chemistry, so along with knocking Max, I figured I’d send her positive energy. I wasn’t sure question marks were technically allowed in senryu, but I found myself using them a lot. Probably because my life felt like one big question mark lately. Like how was I going to start enjoying my newfound freedom?

By midnight, I was zonked. I was going to have to work on my stamina if I wanted to stay out until four. I clicked send, closed my laptop, and crashed.

Seven hours later, the alarm went off. Though I’d been left alone loads of times, I never got used to the feeling of waking to an empty house. Do you know how loud your spoon sounds against your bowl when it’s only you and your cornflakes in the morning?

I showered and dressed and noticed a sick feeling in my stomach. I tried to identify the anxiety. Not grades, not homework; I didn’t even miss my parents yet. What made me woozy was my lack of friends. It’s not like I was an outcast

—

I didn’t wear panty hose, I wasn’t the girl who drew spiderwebs all over her face

—

but my best friend graduated last year and I’d been the unofficial mascot of her class. So it wasn’t only Abby I missed, it was everyone.

Still, I managed to drag myself out the door and my foot nudged something on the mat. A plain white envelope.

A secret admirer? A love letter from Jared?

No, a letter of resignation from Susan. Effective immediately. There were two pages of eloquent regrets, but basically all she said was “I quit.”

Hmm … what was I supposed to do about this? No reason to panic. Maybe my parents had already hired a backup employee. Or maybe they’d be coming home early, before I even had a chance to enjoy their absence.

I walked the block to the bus stop, then ran the last few feet to catch it. I found a seat, took a deep breath, and pulled out my cell to dial Susan.

She answered on the first ring. “You got my letter?”

“You can’t quit now!” I said. “My parents just left for Paris. I’m all alone. Who’s going to run the store?”

“You.”

“Me?” But then I’d have no time for shopping sprees, nightlife, or even a tattoo. Maybe I’d just get a belly ring.

“I’m sorry, Emma. I got another job. In Santa Barbara,” she said, her voice warm and motherly and completely unyielding. “I want to be closer to Abby.”

I swallowed. “Is this about Max?”

“No,” she said. “This is about Abby.”

“I don’t understand why she isn’t talking to me.”

After a moment she said, “I think it’s better if you stop e-mailing her.”

“I just

—

I miss her …” If she were still here, this whole freedom thing would’ve been a lot more fun.

Susan said, “I left a voice mail with your parents and I’m sure they’ll come right back. I’m sorry, Emma. I really am.”

Then she hung up.

The bus heaved to a stop in front of my school. I watched other students trickle off, meeting their friends on the steps. I stepped out, greeted no one, and walked into the main hall alone, yearning to be anywhere but here.