Decipher (36 page)

Authors: Stel Pavlou

[In Ancient Chinese Culture] a man absorbed with writing was absorbed not just with words but with symbols and, through the art of writing with the brush, with a form of painting and thus with the world itself. To the lover of high culture, the way in which something was written could be as important as its content.

Â

David N.

Keightley, “The Origins of Writing in China”

An essay in:

The Origins of Writing,

Edited by Wayne M. Senner, 1989

Keightley, “The Origins of Writing in China”

An essay in:

The Origins of Writing,

Edited by Wayne M. Senner, 1989

Hieroglyphics, from the Greek word

ierolyphika

, meaning “sacred carved letters.”

ierolyphika

, meaning “sacred carved letters.”

Across November's screen were displayed a series of glyphs that seemed to defy understanding. This was the earliest known system of writing ever discovered: the first protocol. It dated even from before the time of Babel, when the divine speech of Adam was smashed into a thousand tongues by God, made all the more confusing by the fact that there were only sixteen symbols.

“That's it?” Sarah was amazed. “That's not much of an alphabet. Is that enough to cover all sounds in a language?”

“Not our language,” Scott agreed, “but some languages? Sure. Scandinavian Runes only had sixteen symbols. That was enough for them. The Old Germanic Runes used twenty-four. Rune, by the way, does

not

mean âmystery' or âsecret,' as the mystics seem to think. It means to scratch, to dig, or to make grooves.”

not

mean âmystery' or âsecret,' as the mystics seem to think. It means to scratch, to dig, or to make grooves.”

“How dull,” Hackett remarked.

“Do you think this language might be related to Runes?” November asked.

“No,” he said confidently. “Runes evolved from Latin letters anywayâthe same letters we still use today.”

“Runes are too modern. I get it.”

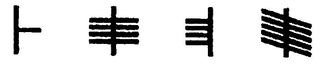

“Right. And the reason they look so different is because of the medium they used. Look.” He grabbed a pen and his notebook. Scrawled out a few letters. “Y'see, these are Runes. This is Futhark writing:

That's nothing like what we're seeing on the screen. Runes are all straight lines because everything was scratched into wood or stone. It's simply too cumbersome to try and even attempt curves. Ogham, the Old Irish language from about two thousand years ago, is the same. It consisted of lines and dots, mostly etched into the corners of standing stones.” He drew a few of those symbols too.

“That vertical line you see is usually drawn first, and all the side lines are drawn going vertically down a continuous mid-line. It's usually up to groups of five lines on any one side because it evolved from a finger language. Which side of the line denoted the left or the right hand. It was also adopted by the Picts on the British Isles. But their language is totally unknown so their Ogham texts, even though we can make out some of the letters, are still undeciphered.”

“But this C60 is crystal. It's hard. So why has this writing got curves, if it's so difficult to make?” November asked reasonably.

Hackett tried his best not to sound brusque. “That's what I was saying, back in the lab! This writing shows no signs of having been etched into the crystal. In fact, it seems to be a natural side effect of the way in which this crystal was manufactured. Like it's part of the design.”

“Is that possible,” she asked, “to grow a crystal to a certain shape by design?”

“Sure,” Sarah interjected. “Airline manufacturers do it all the time. The rotary blade of a jet engine is grown out of a single crystal of metal. It's designed that way because it's stronger. More able to take the pressure ⦔ Sarah went quiet as she realized what she was saying. “Hey, could all those C60 structures we've found be single crystals?”

“That would go a long way to explain how they survived thousands of years, some of them, miles under the ice,” Hackett nodded.

But Scott was elsewhere, completely absorbed in the writing.

“So I guess, if you want curves any other way you've gotta paint 'em on,” November prodded.

“Huh? Oh, yeah. That's what the Chinese did. Demotic, the shorthand version of hieroglyphicsâthat was painted. Once you painted it you could use curves, pictures, all sorts.”

“Hey, they used curves and pictures in Egypt, all over

their monuments,” Sarah corrected. “Remember? I've just been there.”

their monuments,” Sarah corrected. “Remember? I've just been there.”

“Yes. But they're ornamental. They're big. By that reckoning, if you wanted to read the latest novel you'd have to literally wait to read the library from wall to wall. You wouldn't write that large in everyday living. Any Egyptian writing the size of your handwriting is painted, whether it's on a wall or parchment. It's just too intricate to be cast in stone. And in fact, in Chinese, the earliest known writing isn't painted at all. It's scratched into pottery and consists entirely of straight lines.”

“How many characters did that have?”

“Thirty. Written mostly on pottery in Pan-p'o Village, Sian, Shens, about 5000 B.C.E. Some epigraphers have dismissed them because they're not pictograms. They're abstract.”

“They're saying early man wasn't capable of abstract thought?” Sarah chided. “If they're not pictograms then they're not writing. Isn't that a little arrogant? Didn't they ever stop to consider maybe their theory was wrong, and not the facts?”

Scott agreed with her warmly.

“Dr. Scott,” November said, “didn't you say early cuneiform was more complicated and abstract than later cuneiform? As if humans were advanced but seemed to be forgetting their knowledge base?”

“Yup. And the same thing's going on in China. The trouble is, there's little evidence that Chinese writing was ever pictographic, so they can't just dismiss it on that score. Except for what they found in the Shantung region, by a group known as the Yi, who settled in the Lower Yangtze,” he revealed. “Totemism. Pictorial designs thousands of years oldâof the sun and a bird, together. Read as:

yeng niao

. Sunbirds.”

yeng niao

. Sunbirds.”

“The Phoenix again,” November remarked.

Scott nodded. “Anyway,” he said, “Chinese is logographic. Started out in a similar fashion to hieroglyphics. They used pictures based on sounds denoting what they wanted to say. For example, it's like you might draw a pear fruit for the word âpair,' even though it has an entirely different meaning. It's the sound that's important.”

As Scott said all this, his eyes never left the screen. Never wavered from the symbols in his hunt for their meaning. It was like the spew of information was really an autopilot response, something for his mouth to do while his mind went into overdrive.

“It's also called the rebus principle,” he went on, “where pictograms spell out the word in a similar fashion to letters. It was the same in Egyptian hieroglyphics, but it scaled new heights there. You could spell the same word in any number of ways.”

“That must have caused problems,” Hackett suggested.

“Not for them. Just us. We ended up building a whole mystical world around hieroglyphs for a while because we couldn't read them. Stuff like assuming the Egyptians used the symbol of a goose when they wanted to say âson' because they believed the goose was the only bird that loved and nurtured its offspring. When in fact it was just that they're phonetic. The two words sound the same.”

Sarah moved in close to the linguist, equally intrigued by the writing. Asked gently: “So did you get around to figuring out what the hieroglyphics in my tunnel actually spell out?”

Scott said that he had and picked up the notebook he'd left by November's computer. He flipped to the right page and announced:

“Behold! The language of Thoth! The books of wisdom of the Great Enneadâ”

“Behold! The language of Thoth! The books of wisdom of the Great Enneadâ”

“Great Ennead?”

“All the gods together. Kinda like Congress.

Behold!

” Scott continued.

“What secrets lie here! Despair, for they are not to be known by men!

”

Behold!

” Scott continued.

“What secrets lie here! Despair, for they are not to be known by men!

”

Hackett was disturbed. “That's it?”

“That's it. Oh, and then it just repeats it over and overâfor two miles. Interspersed with heroic tales of kings who tried to have it decoded and failed.”

“Great,” Hackett moaned. “That's not what I expected to hear.”

Suddenly, the epigraphist sat bolt upright. “That's it!” he proclaimed. “At leastâthat's what it's

not

!” He ran his finger across the monitor glass. Remembered his studies from when he was an undergrad. “As Sol Worth said in 1975: âPictures can't say ain't!'”

not

!” He ran his finger across the monitor glass. Remembered his studies from when he was an undergrad. “As Sol Worth said in 1975: âPictures can't say ain't!'”

“What are you talking about?”

“Pictograms and iconograms. Pictures. They can't effectively represent verb tenses, adverbs or prepositions. And what they definitely can't do is assert the

non

-existence of what it is they depict. If you wanted to try and communicate with people in the future, you wouldn't use pictograms.” He put his thumb over the symbol of the circle with the cross. “Forget this one. It's the exception. But look at the rest of these. What do they remind you of? A table? A chair? A sack of potatoes?”

non

-existence of what it is they depict. If you wanted to try and communicate with people in the future, you wouldn't use pictograms.” He put his thumb over the symbol of the circle with the cross. “Forget this one. It's the exception. But look at the rest of these. What do they remind you of? A table? A chair? A sack of potatoes?”

November shook her head. “Nothing. They don't look like anything I've ever seen.”

“Exactly,” Scott exclaimed. “They're abstract. That means they're either lettersâA,B,Câor syllablesâch, th, ph.”

Hackett leaned into the screen. “Or they could be numbers,” he suggested.

“They're not numbers,” Scott replied confidently.

“How do you know?”

“I just do.”

“Asking the right types of questions, huh?”

Scott let it pass. Turned to November. “Can this thing give me percentages? Tell me how many times each one of these symbols is used in the texts?”

“Sure,” November said, getting to work on the problem. “You mean like a frequency chart? What will that achieve?”

“Different letters in our own language are used more often than others. The letter E is used far more than, say, the letter Z.” He shared a look with Sarah. For a brief moment it looked like she might even kiss him.

Instead, she rested a hand on his shoulder. “You're a clever man, Richard Scott.”

“Thanks,” Scott replied proudly. But as he returned his attention to the computer screen he caught November scowling at him.

“What is it?” Scott asked innocently.

November went back to her work. “Never mind,” she grumbled.

“What?”

Scott insisted. But November refused to answer.

Scott insisted. But November refused to answer.

Scott pushed his chair back from the computer, looked to

Hackett for support. But the amused physicist simply shook his head and tutted. “Playing with fire,” he whispered. “Playing with fire.”

Hackett for support. But the amused physicist simply shook his head and tutted. “Playing with fire,” he whispered. “Playing with fire.”

Â

The beeping was insistent. Annoying. November's computer had completed its frequency distribution calculations.

“Ah-ha,” Scott enthused, following the young student's every movement as she punched up the data.

There was a spread of figures, ranging from 6.17 percent at the low end for one glyph to 6.36 percent at the high end. The mean was 6.25 percent. Which, as it happened, was exactly the product of 100 divided by 16. In other words, the frequency of each glyph's appearance within the combined texts was equal. No one glyph was more dominant than the next. So it was impossible to tell from the spread of figures just which glyph might be a consonant, and which might be a vowel.

“Damn it!” Scott spat in frustration. “Goddamnit!” Sarah gave him a sympathetic look. Though he appreciated it, he couldn't quite bring himself to make an acknowledgment.

Other books

Autumn Promises by Kate Welsh

Crusade (Eden Book 2) by Tony Monchinski

Un mundo invertido by Christopher Priest

Devil's Pass by Sigmund Brouwer

Red Clocks by Leni Zumas

Tempest Revealed by Tracy Deebs

Randy and Walter: Killers by Tristan Slaughter

The Boy Who Lost Fairyland by Catherynne M. Valente

Ink Exchange by Melissa Marr

1 Odds and Ends by Audrey Claire