Decoded (10 page)

Authors: Jay-Z

Tags: #Rap & Hip Hop, #Rap musicians, #Rap musicians - United States, #Cultural Heritage, #Jay-Z, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #United States, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Biography

After Quincy talked for more than an hour, Bono pulled out a song U2 had recorded earlier in the day. I was traveling with one of those boomboxes that are built into backpacks, the ones skateboarders use, and at three in the morning in that cigar room Bono played his new song for us on that box, eager to hear what we thought—including me, even though he’d never met me before. Later, when he heard me tell Quincy I was going to meet some friends in the morning and head to the south of France for the first time, he offered to fly me to Nice in his plane. I didn’t tell him just how many friends I was traveling with—which was a lot, too many for his plane—but I really didn’t want to impose anyway.

We became friends after that night. Years later, we both became investors in a restaurant in New York, the Spotted Pig in Greenwich Village. One night I ran into him there and he told me he’d read an interview I’d done somewhere. The writer had asked me about the U2 record that was about to be released and I said something about the kind of pressure a group like that must be under just to meet their own standard. Bono told me that my quote had really gotten to him. In fact, he said it got him a little anxious. He decided to go back to the studio even though the album was already done and keep reworking it till he thought it was as good as it could possibly be.

I really wasn’t trying to make him nervous with that quote—and I was surprised to find out that at this point in his career he still got anxious about his work. What I thought I was doing was expressing sympathy. Here he is, Bono, star, master musician, world diplomat, philanthropist, all of that. It was only right that I met him and Quincy Jones on the same night—they’re both already in the pantheon.

I tried to explain all of that to him and we ended up trading stories about the pressure we felt, even at this point in our lives. I explained how I’ve always believed there’s a real difference between rock and hip-hop in terms of how the artists relate to each other. In hip-hop, top artists have the same pressure a rock star like Bono has—the pressure to meet expectations and stay on top. But in hip-hop there’s an added degree of difficulty: While you’re trying to stay on top by making great music, there are dozens of rappers who don’t just compete with you by putting out their own music, but they’re trying to pull you down at the same time. It’s like trying to win a race with every runner behind you trying to tackle you. It’s really not personal—at least it shouldn’t be—it’s just the nature of rap. Hip-hop is a perfect mix between poetry and boxing. Of course, most artists are competitive, but hip-hop is the only art that I know that’s built on direct confrontation.

TAKE YOUR LAST TWO DEEP BREATHS AND PASS THE MIC

There are rap groups, of course, but one thing you’ll hardly ever find in hip-hop is rappers harmonizing on the mic. The rule is one person on the mic at a time. And you have to earn the right to get on the mic. No one just passes you a mic because you happen to be standing there. In the earliest days of hip-hop, MCs had to prove themselves to DJs before they could rock a party. The competition grew from there—after a while it wasn’t just about who could rock the party or the park or the rec center, it was about who could rep the hood, the borough, the city. Then when people started getting record deals, the battles exploded again, but now they were over national dominance and sales.

Sales battles are a hip-hop phenomenon that you just don’t see played out in the same explicit, public way in other genres of music. Rappers can be like gambling addicts who see a potential bet everywhere they look. Everywhere we look, we see competition. A couple years back, when I was still running Def Jam, 50 Cent challenged Kanye West to a battle over who would get the biggest first-week sales numbers. This was when 50’s

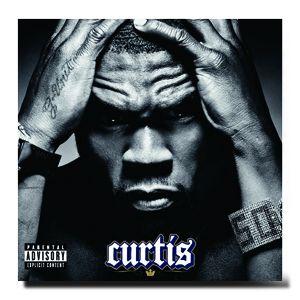

Curtis

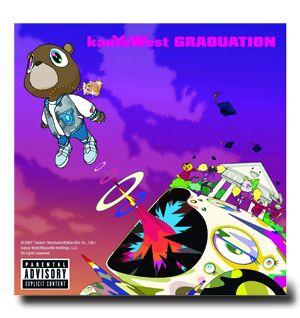

album and Kanye’s

Graduation

were scheduled to come out the same day. The whole thing was fun and useful marketing—and ’Ye won by close to three hundred thousand units—but it was also kind of strange to watch people, regular fans, get so caught up in this battle over numbers. Only in hip-hop.

I’m not complaining. I love the competition—even the sales battles. Before the Kanye situation, I had my own relatively low-key battle with 50 Cent. When I was about to release

The Black Album

we had to push up the release date to get the jump on bootleggers, which put us into the same initial sales week as

Beg For Mercy,

the first album from 50’s crew, G-Unit. 50, in his showman style, got on the radio and announced that he was putting money on

Beg For Mercy

outselling

The Black Album

. This was the same year that 50’s first album,

Get Rich or Die Trying,

had an incredible run, including huge first-week numbers. Kevin Liles at Def Jam called me asking if I wanted to push the date back a couple of weeks to give 50’s album—and some other high-profile releases that week—a chance to breathe. I love Kevin; he’s one of the nicest people you’ll ever meet. But I told him to put my shit out as planned.

The Black Album

debuted at number one,

Beg For Mercy

was third, and the soundtrack to

Resurrection,

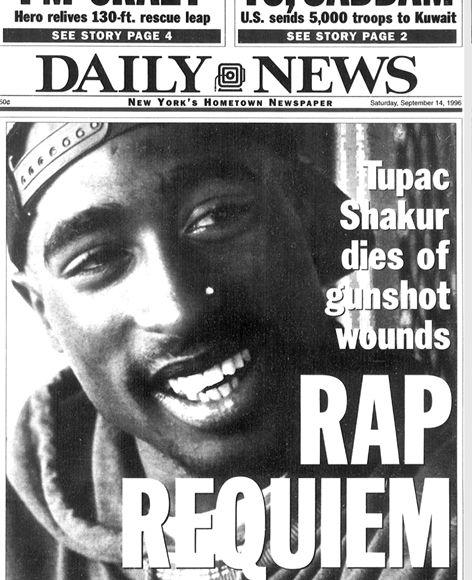

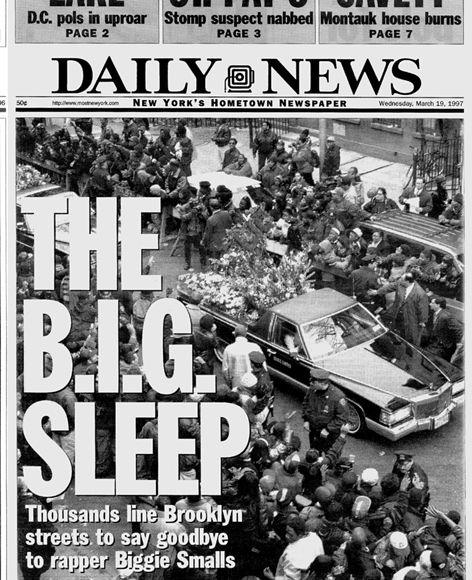

the Tupac documentary, was the number two album on the charts. There was something beautiful about Pac being my closest competition on the charts that week. Aside from the heartbreak of losing two great MCs—and one great friend—I’ve always felt robbed of my chance to compete with Tupac and Biggie, in the best sense, and not just over first-week sales numbers. Competition pushes you to become your best self, and in the end it tells you where you stand. Jordan said the same thing about Larry Bird and Magic. He’d spent this whole career at North Carolina waiting to have the chance to play with them, and by the time Jordan and the Bulls were really coming into their own, Bird and Magic both retired.

But there’s a risk in this kind of indirect, nonmusical “battling”: the spectacle of competition can overshadow the substance of the work. That’s when the boxing analogy breaks down and the more accurate comparison becomes professional wrestling, an arena where the showmanship is more important than actual skill or authentic competition. I’m not a professional wrestler. Rappers who use beef as a marketing plan might get some quick press, but they’re missing the point. Battles were always meant to test skill in the truest tradition of the culture. Just like boxing takes the most primal type of competition and transforms it into a sport, battling in hip-hop took the very real competitive energies on the street—the kind of thing that could end in some real life-and-death shit—and transformed them into art. That competitive spirit that we learned growing up in the streets was never just for play and theater. It was real. That desire to compete—and to win—was the engine of everything we did. And we learned how to compete the hard way.

KNOCKED A NIGGA OFF HIS FEET, BUT I CRAWLED BACK

When I was sixteen years old, my friend Hill and I set up shop in Trenton, hustling, literally, on a dead-end street. There were a couple of areas close by where other hustlers were working: in front of the grocery store, in front of a club on the main strip, out in the park. So we competed on price because we were getting our supply at lower numbers.

We started making some money, and we were styling, too—brand-new Ewings, new gear that wasn’t even sold in Jersey yet. The local girls were loving us. Hill enrolled in the high school just to fuck with the girls. My dumb ass went up to meet him one day at the end of school and I got arrested by the school cop for trespassing; I had crack in my pockets, but since it was my first arrest and I had no prior offenses, they released me on my own recognizance and sealed it once I turned eighteen. But the damage was done—they confiscated the work I was holding. That combined with a series of other setbacks, and suddenly we were in a hole.

I went back to Brooklyn, stressed. I needed to make some money fast to cover the loss. A kid from Marcy owed me money, so I went out with him on the streets and worked for sixty straight hours. I would give him work to sell, wait while he turned it around, then take that money uptown to cop more work. I kept him working three nights in a row. His girl brought him sandwiches in the middle of the night. I stayed awake by eating cookies and writing rhymes on the back of the brown paper bags. Once I’d recovered my money, we headed back to Trenton.

When we got back, we worked even harder, determined to never be in a position where a loss would set us that far back. Meanwhile, kids in Trenton were really starting to hurt from the drop in prices we’d forced on them. Word got back to us that we weren’t welcome in the park. This one kid, a boxer with a missing tooth, got into a hand-to-hand fight with Hill when he walked through the park anyway. We weren’t gonna let some dudes in the park shut us down. It was like playground beef all over again, except niggas are damn near grown men, and holding. So how did we react to the scrap? We went to the park and confronted these cats at four in the afternoon, both sides armed and ready to shoot it out. We faced off and guns were drawn, but luckily nobody got shot. We did get respect. It was stupid and stressful, but we felt we didn’t really have a choice. It was win or go home.