Dedicated to God (16 page)

Authors: Abbie Reese

Tags: #Religion, #Christian Rituals & Practice, #General, #History, #Social History

A novice harvests cabbages grown in the monastery’s gardens. She smiles, caught using hosiery—a novel gardening method—to protect the vegetables from worms.

In general, the nuns observe monastic silence, a custom in which they speak only what is necessary and in a low tone in order to complete a task. One hour a day, during recreation, they can talk freely.

The Mother Abbess was not particularly pleased to discover the holy graffiti that turned up on the greenhouse. Set on the nuns’ cloistered premises, it could only have been their handiwork.

Rockford Poor Clares make and ship the host. Here, a nun stamps out the host after it has been baked.

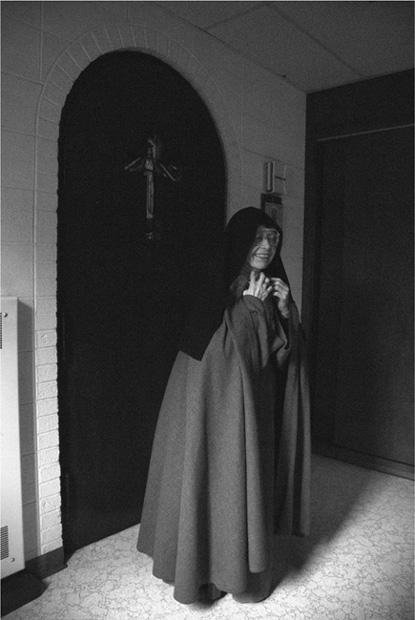

The nuns’ marks hang by paperclips on a radiator next to the door. If a nun goes outside, she indicates this to the rest of her community by removing her marker. When a postulant enters the Rockford Poor Clares, the Mother Abbess assigns her a mark.

3

Monastic Living in a Throwaway Culture

It is a mystical life. The more that God gives to us, the more we give back to Him. And we are freed, because the structure of our life is such that we don’t take on work that is over-encompassing in the mind; the reason for that is so the mind and heart can be with God.

Sister Maria Deo Gratias of the Most Blessed Sacrament

The corridors of the monastery are dark, as usual, the lights off. Mother Miryam walks out of the nuns’ private choir chapel after the Divine Office. She opens a closet and finds her mantle—a heavy cloak. The woolen artifact is a vital layer at the Corpus Christi Monastery in the winter; it keeps the nuns warm in the drafty building, which is heated by a boiler that dates to the building’s construction in the 1960s. The nuns clean and repair the boiler themselves, as much as possible. Mother Miryam has used this same mantle since she entered the monastery in 1955; green-thread stitching denotes her mark—the letter R. (Mother Miryam was assigned this letter when she first joined the community; the Mother Abbess at that time was partial to giving each postulant a letter for her mark—a letter from the name Jesus, Mary, Joseph, Francis, Clare, or Colette.) The cloth in Mother Miryam’s mantle is worn and thin. She jokes about these “old rags” that she loves. The garment has been mended many times, the fabric unraveled and reused; it is precious because she helped make the mantle more than fifty years ago. “I hate to give it up,” she says. “Then I wonder why it’s worn. That’s what amuses me. You wonder, ‘Why is it wearing out?’ It’s been a long time! We expect things to last a long time around here.”

According to the Rule of Saint Clare, the Poor Clare Order was granted the “privilege of poverty” so that the individual members as well as the community as a whole would not own property. Sister Mary Gemma quotes the novel credo, “without anything do I own.” Literally, this means a nun cannot borrow anything from one of her religious sisters because, she says, “it would acknowledge ownership by the other sister of something.” Mother Miryam does not own the mantle; it is for her use. Poor Clare nuns look to God, their superior, and church patrons for sustenance.

This absolute poverty, a pioneering concept at the order’s inception, hails from Saint Francis, the forebear of the Franciscan order of Poor Clare nuns. Saint Francis wrote of his community of friars, “Let the brothers not make anything their own, neither house, nor place, nor anything at all. As pilgrims and strangers in this world, serving the Lord in poverty and humility, let them go seeking alms with confidence, and they should not be ashamed because, for our sakes, our Lord made Himself poor in this world. This is that sublime height of most exalted poverty, which has made you, my most beloved brothers, heirs and kings of the Kingdom of Heaven, poor in temporal things, but exalted in virtue.”

1

The future Pope Gregory IX tried to relieve Sister Clare and her followers, the Poor Ladies, of the harsh tenets, but she held fast, earning approval in decree for “Privilegium Paupertatis,” issued September 17, 1228:

As is clear, by your desire to be dedicated to the Lord alone you have given up your appetite for temporal matters. For this reason, having sold everything and distributed it to the poor, you propose to have no possessions whatsoever, in every instance clinging to the footsteps of Him, who was made poor for our sakes and is the Way, the Truth, and the Life. The lack of goods from this

propositum

does not frighten you, for the left hand of your heavenly spouse is under your head to uphold the weaknesses of your body that you have submitted to the law of the soul through your well ordered love. Accordingly, He who feeds the birds of the sky and clothes the lilies of the field will not fail you in matters of food and of clothing until, passing among you, He serves Himself to you in eternity when indeed his right arm will more blissfully embrace you in the greatness of His vision. Therefore, just as you have asked, we confirm your

propositum

of most high poverty with apostolic favor, granting to you by the authority of the present document that you cannot be compelled by anyone to receive possessions.

2

As elected Novice Mistress at the Corpus Christi Monastery, Sister Mary Nicolette is responsible for overseeing the training and formation of postulants and novices; she buffers young women from a cultural clash. Sister Mary Nicolette helps women make the transition from the outside world; she was nominated and then voted into the position because the other nuns recognize she is uniquely situated, as one of the younger members, to understand the current challenges of adapting to monastic life, and to relate to the young women. “The monastic culture is a culture of itself, of its own. Of its own,” Sister Mary Nicolette says. “So while we have many different sisters coming from different cultures, we all learn the monastic culture when we come.” To this end, Sister Mary Nicolette says an aspiring nun must shed presuppositions and routines, in order to arrive at the monastery with an open disposition to relearn even the simplest of tasks. “When they come we explain to them that you’re relearning everything and you just have to be very humble, you know, and willing to listen,” Sister Mary Nicolette says. “And teachable. Be very teachable.”

Each member of the cultural time capsule that is the cloistered monastery is a product of her upbringing, her familial context, and her geographic framework. Within the enclosure, novices and postulants are integrated gradually into the rest of the community, as required by canon law; they reside in a separate wing from the cells of the professed nuns who have made temporary and permanent vows (typically three and six years, respectively, after entering). Today, the contrast between mainstream culture and the cloistered monastery is so stark, and departure from the world outside to the ancient rules so radical, that novices are given more time than they were given in past decades—one extra year before making final vows—so that they can adapt to monastic life. This steady and gradual immersion is intended to allow them adequate time to discern if they truly are called and to learn if they can adapt to the deliberate environment of unceasing prayer.