Delphi (36 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

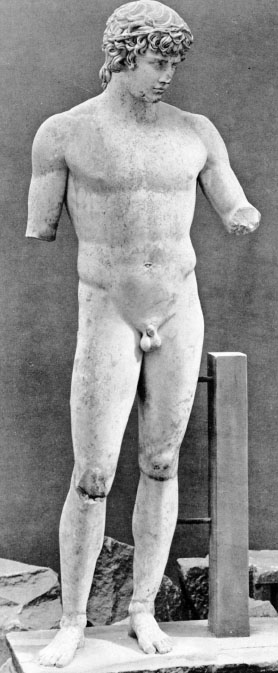

Figure 11.1

. Statue of Antinous dedicated in the Apollo sanctuary at Delphi (P. de la Coste-Messelière & G. Miré

Delphes

1957 Librarie Hachette p. 202)

In the run-up to, and aftermath of the visit in

AD

125, Hadrian's proximity to Delphi seems to have prompted the city to consult him on a number of issues associated with the religious and athletic traditions of the sanctuary. The Imperial correspondence from

AD

125 that was inscribed onto the Apollo temple wall concerned the organization of the Pythian festival and expressed Hadrian's concerns (in response to Delphic queries about changing some of the procedures related to these games) that no traditions should be lost or changed. In the following years, as part of his wider Greek agrarian policy, Hadrian also seems to have been consulted and, as a result, have made significant changes to the management of the sanctuary's sacred land (which was now known simply as “territory”âsee

map 3

), and to the reorganizing of its citizen classes to create a new category of citizen, the

damiourgoi

, who were to be given full civic rights and larger land allotments. The purpose of this reorganization seems to have been to manufacture a particular class of wealthy citizen at Delphi who could fulfill the role of a local governing class. Though not all the letters between Hadrian and Delphi have survived in full, we know that regular correspondence continued through to Hadrian's death in

AD

138, with Delphic praise for the emperor becoming more and more overt. They praised him for assuring the “peace of the universe,” marked the days of his first (and second) visit to Delphi as sacred days in the Delphic calendar, and wrote a number of letters on no particular issue except to express their adoration of him.

7

But Delphi also had something of interest to Hadrian: its Amphictyony. Part of one of his letters to Delphi, dated to around the time of his visit in

AD

125, concerned a reorganization of the Amphictyony council. Several emperors, as we have seen, undertook reorganizations,

yet Hadrian's letter is instructive because of the articulated purpose behind the reshuffle. The letter outlines a reduction in the large Thessalian representation (which had in fact been reinstituted by Nero only in the previous century), and the redistribution of those votes on the council between the Athenians, Spartans, and other cities so that, in the words of the letter, “the council may be a council common to all Greeks.”

8

Such a purpose focuses our attention on two critical facets of the Roman relationship to Greece and particularly to Delphi. First, as we saw in

chapter 10

regarding reorganizations before him (and particularly that of Augustus), the purpose of Hadrian's was to develop a particular kind of council that could undertake a role that, in reality, the Amphictyony had never had during its archaic, classical, and Hellenistic lifetimes. Its council membership had never been a fair representation of all the Greek people; and it was not, despite many modern attempts at analogies, an ancient United Nations or European Union though this is how Romans (and many in the modern world) choose to see it, use it, and characterize it.

9

The second, connected, point concerns Hadrian's wider plan for Greece. In

AD

131â32, Hadrian famously formed the Panhellenionâa union of Greek cities in the Roman province of Achaia that was specifically designed to allow Greece's cultural and historical eminence to sit on equal terms with the more current economic and political muscle of other parts of the Roman Empire, particularly Asia Minor. Constituent members had to prove Hellenic descent, and its members were the famous

metropoleis

of central Greece and their overseas colonies. Many scholars have argued that Hadrian's first instinct was to use the Delphic Amphictyony as the core of such an organization, and that this is why we see this critical restructuring of its membership in

AD

125 in preparation for the formation of the Panhellenion in

AD

131. Yet, what careful study of the documentation has recently pointed out is that Hadrian's letter to the Delphi inscribed on the temple terrace wall in

AD

125 is actually the report of a Roman senatorial commission about potential reform of the Amphictyony (reflecting the Roman misconception of what the Amphictyony was supposed to be), which was in fact later

rejected by Hadrian. Hadrian's Panhellenion was, it seems, always, in Hadrian's mind at least, a separate entity that would in fact be centered around Athens, and that led, in Athens, to the creation of a sanctuary of Hadrian Panhellenius, Panhellenia athletic games, and the embellishment of the nearby sanctuary at Eleusis.

10

Yet, even though Delphi and its Amphictyony may not have been the inspiration or original focus of Hadrian's plans for a united Greece, the Greeks certainly responded to Hadrian's keenness for the concept of a united Greece articulated specifically through the sanctuary at Delphi. In the early years of Hadrian's reign, and before the creation of the Panhellenion, a statue of the emperor was erected at Delphi by the “Greeks who fought at Plataea.”

11

This is the only dedication made in the sanctuary's history by this particular grouping, although of course it made an instant connection to Delphi's perhaps most famous monumental dedication, the three twisted serpents supporting a golden tripod set up for the victory at Plataea in 479

BC

by the Greeks. The united Greek front achieved during the Persian Wars had been, ever since, a key part of any call for Greek unity, and it is not unsurprising that a collection of Greeks chose to reactivate this banner to demonstrate unity to Hadrian through honoring him with a statue in the very sanctuary in which such unity had originally (centuries earlier) been most monumentally displayed.

The level of contact and care lavished on this sanctuary by Hadrian during his reign represents without doubt a high point in Delphi's history. It was a blessing Delphi was to enjoy, after Hadrian's death in

AD

138, for much of the rest of the second century

AD

, and it came in several formsâfirst, through continued interaction with the emperor and other important Roman officials. Hadrian's successor, Antoninus Pius, became archon of the city, and his image appears on a series of Delphic coins, the last major series of coins minted at Delphi in its history, most probably struck for the occasion of its ongoing and successful Pythian games. And Valeria Catulla, the wife of Tiberius Claudius Marcellus, a Roman official in Greece during the second half of the second century

AD

, set up a statue in the sanctuary in Antoninus's honor with the agreement of the Amphictyony.

12

Second was through a growing interest in

and use of the sanctuary as a base for philosophical thinking. Since the end of the first century

AD

, Delphi had been acquiring a reputation as a locus for philosophical discussion, thanks to its unique combination of history, oracle, philosophical heritage, and athletic and musical competitions, which even other Panhellenic periodos sanctuaries could not match. It was a reputation much enhanced by Plutarch's time as priest of Apollo and the dissemination of many of his philosophical discussions about Delphi and other matters (see

fig. 10.1

).

13

As a result, Delphi was visited by a significant number of philosophers and sophists during the second century

AD

, such as Aulus Gellius who attended with his students to watch the Pythian games in

AD

163. At the same time, a number of statues of Sophists were erected in the sanctuary both by the city of Delphi and by other cities like Ephesus and Hypata, and by groups of Sophists in honor of respected members of their circle.

14

Combined with (and partly as a result of) this Imperial favor and reputation as a philosophical hotspot, Delphi's games also continued strongly in popularity during the second century

AD

. The sanctuary's increasingly packed confines were populated with a plethora of statues to athletic winners and to those tasked with organizing the games (in particular the agonothetes) from the Amphictyony, as well as from cities around the Mediterranean who had previously dedicated in the sanctuary, and sometimes from cities that had never dedicated at Delphi.

15

Ancyra, in Asia Minor, for example, made its only dedication in the sanctuary's history at the end of the second century

AD

, erecting a statue of its victor in the Pythian musical competition. Likewise, Myra (in Lycia in Asia Minor) erected its only offering in the sanctuary's history during the second century

AD

: a statue for its own Pythian victor. So, too, Sardis (in Asia Minor) erected a series of monuments to one of their extremely successful athletes (who had been victorious in a number of the periodos Greek games) at the end of the second century

AD

and the beginning of the third century.

16

This interest in Delphi's athletic and musical competitions reflects Delphi's importance all across the Mediterranean (but especially in the east) during the second century

AD

.

17

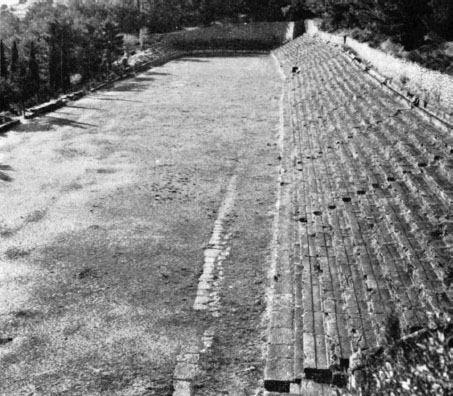

But at the same time, the sanctuary

was the focus of one of Greece's own greatest benefactors from this period: Herodes Atticus. A millionaire aristocrat from Athens, but also of Roman citizenship (and who would be consul in Rome in

AD

143), Herodes Atticus was born at the very beginning of the second century

AD

and died in

AD

177. During his lifetime, he saw Greece flourish under the spotlight of successive Roman emperors (many of whom he encouraged to take an interest in Greece, and with whom he was on excellent terms). More importantly he was himself prolific in building projects designed to enhance both Athens and other cities in the Greek world. At Delphi, he turned his attentionâperhaps unsurprisingly, given the amount of interest in the Pythian games at this timeâto the stadium. What you see today when you visit the site is largely the work of Herodes Atticus (

fig. 11.2

). The stadium's length was reset to measure six hundred (Roman-measured) feet. For the first time in its history, the stadium was given stepped seating in local limestone: twelve levels on the northern side, six on the southern, with curved seating at the western end that allowed for approximately 6,500 spectators. At its eastern end, a monumental entrance was created with arched doorways and niches for statues. As a result of Herodes' enormous benefaction, a number of statues were put up in his honor. One, predictably, comes from the city of Delphi, which also erected one to his wife, Regilla, and to Herodes' disciple Polydeucion. In contrast, it is interesting that we have no record of the Amphictyony erecting a statue in Herodes' honor. But Herodes Atticus seems also to have been keen to erect statues in honor of his own family and circle in the sanctuaryâof his wife, more than one of his daughter and son and Polydeucion; and in turn his wife set up a statue of him And all these were placed prominently near the temple of Apollo.

18

Herodes Atticus died in

AD

177, during the reign of Marcus Aurelius (AD 161â80), who had himself taken the cue from his predecessors (and indeed his co-emperor Lucius Verus

AD

161â69) and continued a close relationship with Delphi. Both Lucius and Marcus confirmed the continued independence and autonomy of Delphi as a city, and Marcus Aurelius seems to have kept up a lengthy correspondence with the sanctuary.

19

We can get some sense of the wealth of Delphic citizens in this period from their tombs, collected in burial areas (necropoleis) surrounding the city and sanctuary (see

plate 1

). We know, for example, that an underground crypt was created during the Imperial period in one of the necropoleis to the west of the sanctuary. While it is difficult to date the crypt specifically, we can be more certain of the date for a large, ornate, and expensive sarcophagus from the second century

AD

, now on display outside the Delphi museum (

fig. 11.3

). It is known as the sarcophagus of Meleager because of the mythological scene carved around it, and it was an expensive choice for whomsoever was originally buried in it. Indeed it was so much admired that it was reused as many as fifteen times for additional burials between the second and fifth centuries

AD

.

20