Delphi (25 page)

Authors: Michael Scott

In the years after 346

BC

, the rebuilding of the temple and sanctuary moved forward apace, reinfused as it was with energy and money thanks in no small measure to the Phocian fine flowing annually into Delphi's coffers. The renovations were extensive: the terracing wall to the temple terrace was raised in height, the entire floor plan of the temple was moved farther north, necessitating excavation and rebuilding of the terracing wall to the north to create extra space. Sets of stairs were inlaid into this new terracing wall to lead to the area later occupied by the theater. There was significant investment in systems to channel water as it flowed down the mountainside around and underneath the temple platform. A new temple was planned with new pedimental sculpture, so the surviving pedimental sculpture from the previous Apollo temple, like the famous charioteer statue, was buried just to the north of the temple terrace, along with dedications damaged in the 373

BC

earthquake. New access routes were laid out above these burials between the north of the sanctuary and

the temple terrace, with previous dedications moved around and repositioned to line these routes, and at the same time areas of cult worship to a variety of deities and heroes were likely more fully developed, for instance, the cult area around the “tomb” of Neoptolemus just to the north of the temple (see

plates 1

,

2

;

figs. 1.4

,

7.2

).

46

But the Phocian fine, it seems, had encouraged the Amphictyony to develop their plans even further. Some of the dedications that were melted down by the Phocians (particularly Croesus's gold and silver craters) were remade. Money was also put to use to create new structures at Delphi: a gymnasium and stadium, for instance, to provide better facilities for its increasingly popular Pythian games (

fig. 7.3

). The stadium, dramatically positioned now up above the Apollo sanctuary, had copies of its older rules and regulations laid into its stone walls (see

plate 1

). One inscription, still in place today, forbids the taking of sacrificial wine out of the stadium on pain of a large fine. It seems that those tasked with the reinscribing of this old rule were uncertain how to render it in fourth-century style. The result is an inscription in which the letter forms are a curious mix of centuries: an archaic theta but a fourth-century alpha, for example, and even a misspelling of the word “wine” because, by then, an entire letter that used to be in the word (the digamma) had slipped out of usage and was unrecognizable to the fourth-century letter cutters.

47

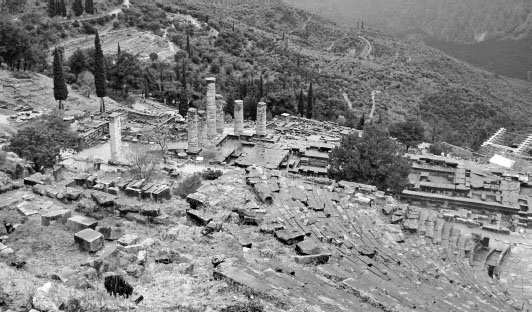

Figure 7.2

. The fourth century

BC

temple of Apollo in the Apollo sanctuary at Delphi as seen today from the theater above it (© Michael Scott)

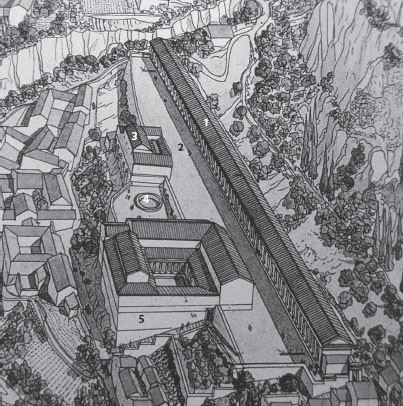

Figure 7.3

. A reconstruction of the gymnasium at Delphi (aquarelle de Jean-Claude Golvin. Musée départemental Arles antique © éditions Errance). 1 Covered running track. 2 Outdoor running track. 3 Roman baths. 4 Washing pool. 5 Palestra.

The gymnasium, on the other hand, was built nearer the Castalian fountain, next to the Athena sanctuary, on land mythically considered

the location where Odysseus had been wounded in the thigh by a boar (see

plate 1

,

fig. 7.3

). It was one of the first architecturally complex gymnasiums built in Greece, putting Delphi at the forefront of Greek architectural and athletic development, and it consisted of both a covered and outdoor running track, a wrestling area, and bathing facilities. The Pythian games benefited from the building of these new facilities: additional events were added to the games in the fourth century, and it is now, in the late 340s and 330s, that the first attempts are madeâby Aristotle and his nephew Callisthenes no lessâto record a list of all the Pythian victors stretching back to the beginnings of the games in the sixth century, a list eventually put on display in the sanctuary, and for which laborious effort Aristotle and Callisthenes received honors from the Delphians.

48

If all this was not enough, the Phocian fine was also channeled by the Amphictyony toward their other sanctuary, that of Demeter at Anthela, and used to produce the Amphictyony's first, and only, currency (

fig. 7.4

). The one place conspicuously not to benefit from the fine seems to have been the sanctuary of Athena at Delphi (although its damaged tholos and temple were repaired). At the same time, its two treasuries seem to have been converted for use in some kind of civic/private function and were surrounded by inscribed steles documenting civic affairs, perhaps an indication that this sanctuary had come more recognizably under the control of the Delphic polis at a time when relations between the Amphictyony and Delphi must have been strained (see

plate 3

).

49

Figure 7.4

. Coinage issued by the Amphictyony at Delphi between 336 and 335â35

BC

. This stater coin has Demeter on one side (due to the Amphictyony's responsibility for the sanctuary of Demeter at Anthela), and Apollo sitting on the omphalos on the other. “Amphictyony” is spelled out on the coin around the rim (© EFA/Ph. Collet [Guide du site fig. 2.f])

Despite tense relations at Delphi, this burst of building activity and reflowering of the Amphictyony, coupled with the ongoing articulation in the literary sources at this time of the events surrounding the First Sacred War in the early sixth century, seems to have once again encouraged dedicators to invest in the sanctuary. The Cnidians returned to spruce up their lesche and the surrounding area. The Thebans and Boeotians celebrated the outcome of the war with new dedications. The Cyreneans, fundamentally tied to Delphi throughout their history, and now contributors to the fund to rebuild the temple, returned to dedicate a marble treasury in the Apollo sanctuary (see

plate 2

), for which they were awarded promanteia, to complement their other fourth-century dedication: a chariot sculpture with a figure of the god Ammon. Likewise, the Rhodians, chose to build a sculpture of the god Helios with his sun chariot, which was placed atop a high column on the eastern edge of the temple terrace, directly on the axis of the new temple (see

fig. 1.3

).

50

But it was this temple that was soon again to spark controversy. By 340

BC

, it was complete enough for the Athenians, still spoiling for a fight having felt cheated by Philip of Macedon in the peace agreed in 346

BC

, to rehang the Persian shields the Athenians had placed on the metopes of the previous temple after their great victory against the Persians at Marathon in 490

BC

. In a sanctuary already teeming with examples of the rewriting of history to suit present circumstances, this was one in which history was deliberately not rewritten to make a point. The rehanging of the same old shields pointed to the continued glory of Athenian history, but also, more specifically, to the past misdemeanors of Thebes, a city now enjoying considerable influence, but which, according to the inscriptions on the shields, had fought with Persia against Greece back in the fifth century

BC

.

51

Such an undiplomatic slap in the face could not go unnoticed. At a meeting of the Amphictyonic council in 340

BC

, the representative of the Ozolian Locrians accused the Athenians (without doubt, pushed by Thebes and Philip) of impiety for not performing the proper rituals before erecting the shields. Athens's man at the council was Aeschines, an orator who, in Athens, was a natural supporter of Philip (and thus

archenemy of Demosthenes), but who now was called on to defend Athens on a larger stage against Philip's machinations. His speech to the assembly, as he himself later recalled, brilliantly turned the tables on Athens's accusers. The Locrians were guilty, he argued, of a greater impiety in cultivating sacred land. His rhetoric was enough to spark a military attack then and there against the Locrians, an attack the Locrians easily repelled because neither the Amphictyony nor the city of Delphi had a proper standing army. As 340 gave way to 339

BC

, the Amphictyony called a special meeting to organize a proper military force. But by this time, Athens had realized that pushing this war was not in their best interests long-term: the city was conspicuously absent from the emergency meeting, as were the representatives of their main enemy Thebes. The result was that the paltry forces of the Amphictyony were able to evict the Locriansâand particularly the citizens of Amphissaâfrom the sacred land, but unable to enforce any kind of permanent solution. In exasperation, the Thessalian commander of the Amphictyonic forces turned (once again) to Philip of Macedon.

52

It was exactly the invitation Philip had been waiting for. Fed up with Athens snapping at his heels, Philip used the invitation to sweep south with his forces. Instead of marching on Amphissa, he set up camp at Elatea, just a couple of days march from Athens. Athens's diplomatic posturing had led to the prospect of its invasion. In desperation, Athens was forced into an alliance with the same city it had hoped to antagonize in the first place: Thebes. In late September 339

BC

, Athens consulted the Delphic oracle on ill omens witnessed at their festival of the Mysteries at Eleusis. Demosthenes, Philip's most vocal opponent, architect of the new alliance between Thebes and Athens, denounced Delphi's response with the bitter words “the Pythia is Philipizing.” In the winter of 339â38, Athens and Thebes marched to occupy Phocis and Delphi as a brave forward move against Philip. In return, in the summer of 338

BC

, Philip turned to meet them. He occupied Locris, punished Amphissa as per his original agreement with the Amphictyony, and faced Athens and Thebes on the battlefield at Chaeronea, just on the other side of the Parnassian mountains from Delphi. It was a cataclysmic event in Greek history: the

forces of Athens and Thebes were decimated, leaving Philip triumphant and in charge of mainland Greece.

53

So ended what became known as the Fourth Sacred War. Amphissa, terrorized into submission by Philip, promptly put up a statue of him in the Apollo sanctuary at Delphi, calling him “

basileos

” (“king”) (it was their first and only civic dedication in the sanctuary).

54

It was a moment, finally, for the Greeks, and particularly the Delphians, to catch their breath. In a single century, their sanctuary had been used as a space in which to trumpet Athenian defeat and Spartan ascendancy, followed by Spartan defeat and Theban ascendency. It had been in ruins since 373

BC

, during which time the Delphians had faced prospective takeovers from Thessaly; actual occupations by the Phocians; two Sacred Wars; the dramatic loss of many of their most precious offerings; the adrenaline shot of the Phocian fine, which had not only replenished their coffers, but had seen their sanctuary rebuilt and expanded; the articulation not only of a newly empowered Amphictyony but of a mythic history of their involvement with the sanctuary dating back to the First Sacred War; and the arrival and imposition of Philip and the power of Macedon over mainland Greece. It had been a roller coaster ride. Perhaps now, they thought, things would settle for a while? They could not have been more wrong.