Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (214 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

Whence had come this idea that wealth bought happiness? Not from the rich. Surely they must have learnt better by this time.

It was not the enjoyable things of life that cost money. These acres of gardens where one never got away from one’s own gardeners. What better were they than a public park? It was in the hidden corner we had planted and tended ourselves — where we knew and loved each flower, where each whispering tree was a comrade that we met God in the evening. It was the pleasant living-room where each familiar piece of furniture smiled a welcome to us when we entered that was home. Through half-a-dozen “reception-rooms” we wandered, a stranger. The millionaire, who, reckoning interest at five per cent., paid ten thousand a year to possess an old master. How often really did he look at it? What greater artistic enjoyment did he get out of it than from looking at it in a public gallery? The joy of possession, it was the joy of the miser, of the dog in the manger. Were the silver birches in the moonlight more beautiful because we owned the freehold of the hill?

She remembered her walking tours with Jim. Their packs upon their backs, and the open road before them. The evening meal at the wayside inn, and the sweet sleep between coarse sheets. She had never cared for travel since then. It had always been such a business: the luggage and the crowd, and the general hullaballoo.

What would the children say? Well, they could not preach, either of them: there was that consolation. The boy, at the beginning of the war, and without saying a word to either of them, had thrown up everything, had gone out as a common soldier — he had been so fearful they might try to stop him — facing death for an ideal. She certainly was not going to be afraid of anything he could say after that.

Norah’s armour would prove even yet more vulnerable. Norah, a young lady brought up amid all the traditions of respectability, had dared even ridicule; had committed worse than crimes — vulgarities. A militant suffragette reproving fanaticism need not be listened to attentively.

But this case she was thinking of was exceptional. Whatever Anthony and she might choose to do with the remainder of their lives need not affect their children. Norah and Jim would be free to choose for themselves. But the young mother faced with the problem of her children’s future? Ten years ago what answer would she herself have made?

The argument took hold of her. She found herself working it out not as a personal concern, but in terms of the community. Was it necessary to be rich that one’s children should be happy? Childhood would answer “no.” It is not little Lord Fauntleroy who clamours for the velvet suit and the lace collar. It is not Princess Goldenlocks who would keep close barred the ivory gate that leads into the wood. Childhood has no use for riches. Childhood’s joys are cheap enough. Youth’s pleasures can be purchased for little more than health and comradeship. The cricket bat, the tennis racquet, the push bike, the leaky boat that one bought for a song and had the fun of patching up and making good, even that crown of the young world’s desire, the motor-cycle itself — these and their kindred were not the things for which one need to sell one’s soul. Education depended upon the scholar not the school. Was the future welfare of our children helped by our being rich? — or hindered?

Suppose we brought up our children not to believe in riches, not to be afraid of poverty; not to be afraid of love in a six-roomed house? Not to believe that they were bound to be just twice as happy in a house containing twelve, and thereby save themselves the fret and frenzy of trying to get there: the bitterness and heart break of those who never reached it. The love of money, the belief in money, was it not the root of nine-tenths of the world’s sorrow? Suppose one taught one’s children not to fall down and worship it, not to sacrifice to it their youth and health and joy. Might they not be better off — in a quite material way?

It occurred to her suddenly that she had not as yet thought about it from the religious point of view. She laughed. It had always been said that it was woman who was the practical. It was man who was the dreamer.

But was she not right? Had that not been the whole trouble: that we had drawn a dividing line between our religion and our life, rendering our actions unto Cæsar, and only our lips unto God? Christianity was Common Sense in the highest — was sheer Worldly Wisdom. The proof was staring her in the face. From the bay of the deep window, looking eastward, she could see it standing out against the flame-lit sky, the great grey Cross with round its base the young men’s names in golden letters.

The one thing man did well — make war. Man’s one success — the fighting machine. The one institution man had built up that had stood the test of time. The one thing man had made perfect — War.

The one thing to which man had applied the principles of Christianity. Above all things required of the soldier was self-forgetfulness, self-sacrifice. The place of suffering became the place of honour. The forlorn hope a privilege to be contended for. To the soldier, alone among men, love thy neighbour as thyself — nay, better than thyself — was inculcated not as a meaningless formula, but as a sacred duty necessary to the very existence of the regiment. When war broke out in a land, the teachings of Christ were immediately recognized to be the only sensible guide to conduct. At the time, Anthony’s suggestion had seemed monstrous to her: that he should ask her to give up riches, accept poverty, that he should put a vague impersonal love of humanity above his natural affection for her children and herself! But if it had been England and not God that he had been thinking of — if, at any moment during the war, it had seemed to him that the welfare of England demanded this, or even greater sacrifice, she would have approved. The very people whose ridicule she was now dreading would have applauded. Who had suggested to the young recruit that he should think of his wife and children before his country, that his first duty was to provide for them, to see to it that they had their comforts, their luxuries; and then — and not till then — to think of England? She had regarded his determination to go down into the smoky dismal town, to live his life there among common people, as foolish, fantastic. He could have helped the poor of Millsborough better by keeping his possessions, showering down upon them benefits and blessings. He could have been of more help to God, powerful and rich, a leader among men. As a struggling solicitor in Bruton Square of what use could he be?

Had she thought like that, during the war, of the men who had given money but who had shirked the mud and blood of the trenches — of the shouters who had pointed out to others the gate of service?

Neither rich nor poor, neither great nor simple — only comrades. Would it ever be won, the war to end war — man’s victory over himself?

The pall of smoke above the distant town had merged into the night. In its place there gleamed a dull red glow, as of a pillar of fire.

She turned and faced herself in the great cheval glass with its frame of gilded cupids. She was still young — in the fullness of her life and beauty; the years with their promise of power and pleasure still opening out before her.

And suddenly it came to her that this was the Great Adventure of the World, calling to the brave and hopeful to follow, heedless, where God’s trumpet led. Somewhere — perhaps near, perhaps far — there lay the Promised Land. It might be theirs to find it — at least to see it from afar. If not — ! Their feet should help to mark the road.

Yes, she too would give up her possessions; put fear behind her. Together, hand in hand, they would go forward, joyously.

THE END

The Short Story Collections

St. Marylebone Grammar School, which Jerome attended as a boy

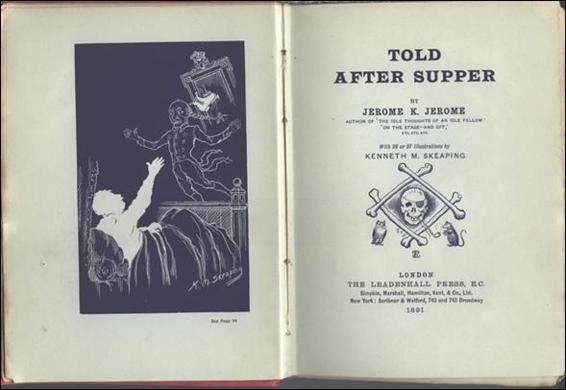

TOLD AFTER SUPPER

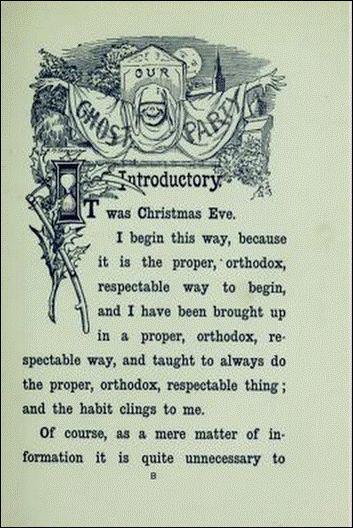

This short story collection was first published in 1891 and provides parodies of traditional Victorian ghost stories, particularly those told by authors like Charles Dickens. The collection’s narrative frame echoes the structure of some of Dickens’ co-authored supernatural collections and contains eight stories (some of them very short), each told after supper by friends that are gathered together on Christmas Eve. Although the tales are told by different people, they are related through one narrator – arguably the real focus and target of the story’s satire. The narrator’s comical determination to adhere strictly to the generic expectations of the ghost story is cleverly linked with his insistence upon ‘orthodoxy’ in areas of social behaviour. In this, the narrator strongly resembles Mr Pooter, the central character of the Grossmith brothers’

The Diary of a Nobody

, in that his attempts to conform to what he sees as traditional forms of behaviour are constantly and humorously thwarted by mundane trivialities – a common theme found in Jerome’s work.

The title page of the first edition, lavishly illustrated by Kenneth M. Skeaping

CONTENTS

HOW THE STORIES CAME TO BE TOLD

JOHNSON AND EMILY, OR THE FAITHFUL GHOST

INTERLUDE — THE DOCTOR’S STORY

THE HAUNTED MILL, OR THE RUINED HOME

As well as providing almost a hundred illustrations for the collection, Kenneth M. Skeaping also designed elaborate chapter headings such as the one shown above