Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) (514 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Jerome K. Jerome (Illustrated) (Series Four) Online

Authors: Jerome K. Jerome

Manager: “No, I couldn’t. I merely throw out the idea to you, as I know something about these things.”

Shakespeare: “Then it’s no good, of course, my leaving it with you any longer”

(taking it from the table and looking sadly at it).

Manager: “None whatever, my boy.”

Shakespeare: “Well, thank you very much for having read it, sir. Good morning.”

(Manager, absorbed in his letter, makes no response, and Shakespeare, taking up his hat and trying to fix his MS. under his coat so that it will not be seen, goes out, closing the door softly behind him.)

APHORISMS TAKEN FROM

TO-DAY

“Reason no more makes wisdom than rhyme makes poetry.”

“The value of an idea has nothing to do with the sincerity of the man who expresses it.”

“Knowledge collects, wisdom corrects.”

“The cynic has little hope, less faith, and least charity.”

“Man must go up, go down, or go out.”

“The chief function of fools is to teach — what to avoid.”

“The easiest to do is often the hardest to bear.”

To-day

was a great success; but it caused Jerome to appear in two civil actions in the High Court of Justice. Immediately after the first number was published Jerome and his business manager brought an action against the printer of the journal for defective printing. One particular complaint was that an autograph letter from the Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone was obscure and almost unreadable. Jerome won the case and the jury awarded one farthing damages.

There was some chaff indulged in by J. K. J.’s friends. “

To-day

,” they said, “was now being edited by a bloated capitalist.” In a later number, Jerome wrote that something better than the printing of the first number could be done and was going to be done, “even if I have to take special lessons in language from Lord Randolph Churchill to accomplish it.”

An editor’s path is beset with many pitfalls. He has to be careful in handling hazardous reports. The law of libel has to be strictly observed. It is an anxious occupation, especially to a man who fearlessly speaks his mind in the interests of fair dealing and honest trade.

The second action was one brought against Jerome by Mr. Samson Fox, a Leeds company promoter, whose case was that he had been libelled by the editor of

To-day.

Mr. Fox’s leading counsel was the Right Hon. H. H. Asquith, Q.C., M.P. Jerome engaged Sir Frank Lockwood, Q.C., whose clever and humorous drawings had from time to time appeared in

To-day.

The learned Judge (Baron Pollock) in summing up stated that “the action had taken a longer time than any other action for libel that he could recollect, and his recollection went back over fifty years”. The case resolved itself into an argument as to whether gas could be made out of water. The conclusion arrived at was that it remained to be seen.

Jerome lost this case. The damages were one farthing. The jury, it would seem, had a sense of humour. The farthing that J. K. J. won in the previous action and on which, it was said, he had fared sumptuously every day, had to be handed over to a wealthy Yorkshire magnate. But, the farthing apart, each had to pay their own costs. The trial cost J. K. J. nine thousand pounds and Samson Fox eleven thousand pounds.

Much sympathy was felt for Jerome. One of the best-known editors in London wrote to him:

“Heartiest congratulations upon the public service

To-day

has rendered.”

This gentleman also suggested a million farthing fund, “that those who know the present-day necessity for straightforward financial criticism may enjoy the satisfaction of subscribing the damages a million times over”.

Jerome discouraged the idea, but the heavy costs brought to an end his career as a journalist. It was an overwhelming blow. He had to sell out from

To-day

and

The Idler.

He wrote from Germany to Coulson Kernahan:

My dear Jack, Can you tell me if

To-day

is dead yet? If not, will you send me over a copy? The

To-day’s

creditors are coming down on us. I do not expect to be free from this business till I die....

All best love and wishes, Yours ever, JEROME.

Up to the time of this action,

To-day

had been a one-man paper. It lasted but a short time after Jerome went out. There is a tinge of irony in the fact that in a few years after the trial Mr. Samson Fox became Parliamentary candidate for Walsall, Jerome’s native town. He did not live, however, to contest the constituency.

To Jerome, journalism had been a great game. He had begun at the very bottom of the ladder, and worked his way upward, step by step, through every grade. It had enabled him to get nearer to the great heart of things. The Press was rapidly becoming a powerful force in moulding public opinion, and Jerome had felt the thrill of taking a hand in this enterprise. Journalism was, in fact, the joy of his life, in so far as it enabled him to carry out his early determination to help the weak, to lift up those who are down and to make their lives cleaner and happier.

CHAPTER VI. JEROME K. JEROME AS A DRAMATIST

“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players.”

— SHAKESPEARE.

MUCH of Jerome’s energy had been devoted to Journalism. At the same time he had written much on theatrical matters, revealing his gifts in this direction. Plays were also shaping themselves in his mind. In his spare time, when a clerk at Euston, he had gained some stage experience, and for three years had travelled the country as a roving player.

To reconstruct his career as a writer and a creative dramatist, we must go back to the time when he was a solicitor’s clerk in lodgings with George Wingrave. They had left Newman Street, but still lived together at 33, Tavistock Place, W.C. (since pulled down) to be near the British Museum. The two young men frequently went to the theatre together. They attended “first night” performances; at one of these they became acquainted with Mr. Carl Hentschel, who also was an enthusiastic “first nighter” and “pittite”. After the theatre Hentschel accompanied them to their lodgings. This was the beginning of another intimate and lifelong friendship.

On arriving at their rooms they would “toss up” to decide who should go back into the street to fetch the supper from the fried fish shop. They also had “at homes” at their lodgings on Sunday evenings, and, as one of them recently remarked, matters of grave importance were discussed, and not only the drama but the affairs of the Universe were satisfactorily settled.

About the year 1883 the “Old Vagabond Club” was formed. The original meeting-place was the sitting-room of the blind poet, Philip Marston, at 191, Euston Road. The object of the club was to discuss subjects in connection with literature and the drama. The first “Vagabonds” were Addison Bright (whose grandfather gave its name to Bright’s disease), J. K. J., Coulson Kernahan, Philip Marston, Dr. Westland Marston, Carl Hentschel, and George Wingrave, etc. Pett Ridge joined later.

In the following year “The Playgoer Club” was formed. Jerome, being one of the regular frequenters of the pit on first nights, was a member. The “Pittites” had been in the habit of meeting regularly outside the pit, and the club was formed to enable members to discuss the drama in comfort.

They met at the Danes Inn Coffee House, Holywell Street, the subscription being two shillings and sixpence per week. When they had collected sufficient money they took furnished rooms in Newman Street, W. Thus the first club for playgoers began its career. J. K. J. was the first president. He remained in that office until, several years afterwards, a split occurred and Carl Hentschel, followed by about five hundred members, seceded.

The O. P. Club (Old Playgoers’ Club) was then formed to carry on the original idea of the former club. Jerome was always closely identified with it, and owing to the enterprise of Carl Hentschel (trustee and founder) it rendered invaluable aid to the cause of the drama. The club later occupied rooms at the Hotel Cecil. (It was in a small street where this hotel now stands that Jerome worked as a clerk in a solicitor’s office.)

H.R.H. The Prince of Wales had honoured the club with his presence. H.M. Queen Alexandra also (unsolicited) granted her Royal Patronage. The club has given large sums of money to the Disabled Actors’ War Fund; and has given complimentary dinners to Sir Henry Irving, Dame Ellen Terry, Sir Charles Wyndham, and Jerome K. Jerome. This latter function will be referred to in a later chapter.

In 1885 J. K. J.’s first book “On the Stage and Off” was published. In it he recorded his experiences gained on “the road” as a roving player. He undoubtedly picked up there some of the technique of playwriting, as in the same way did Shakespeare and Ibsen. It was a rough, hard school. He was often the victim of the bogus manager, the swindling agent, and the humbugging unemployed actor. His sense of humour, however, never deserted him, and his difficulties were in reality no great hardship. He knew that no artist could ever begin as a master, and that the deeper mysteries of art are only realized after passing through the furnace. Moreover,

all

is not bad on the turnpike of life. As he himself wrote: “Let the bad pass. I met far more honest, kindly faces than deceitful ones, and I prefer to remember the former. Plenty of honest, kindly hands grasped mine, and such are the hands that I like to grasp again in thought.”

In the following year he wrote a series of articles entitled “Stageland”. These were first published in a monthly journal called

The Playgoer.

The articles were illustrated by Sir Bernard Partridge and were full of delightful humour and diverting satire; they were generally regarded as the best things in the paper. They contained much fun at the expense of the “Stage Hero”, the “Stage Comic Man”, the “Stage Lawyer”, the “Stage Villain”, etc. The following extracts from these cleverly-written articles will, no doubt, be read with interest.

“‘The Stage Hero.’

“The ‘Stage Hero’ is a very powerful man. You wouldn’t think so to look at him, but you wait till the heroine cries: ‘Help! Oh, George, save me!’ and the police attempt to run him in. Then two villains, three extra hired ruffians, and four detectives are about his fighting weight. If he knocks down less than three men with one blow, he fears he must be ill, and wonders ‘Why this strange weakness?’

“‘The Stage Comic Man.’

“The chief duty of the ‘Comic Man’s’ life is to make love to the servant girls, and they slap his face, but it does not discourage him, he seems to be more smitten by them than ever. Like the Irishman, he is happy under any pretence, he says funny things at funerals, or when bailiffs are in the house, or the hero is waiting to be hanged. In real life such a man would probably be slaughtered, but on the stage they put up with him.

“‘Stage Peasantry.’

“The ‘Stage Peasantry’ like to do their love-making in public. Some people fancy a place to themselves for this sort of thing — where nobody else is about. We ourselves do, but the ‘Stage Peasant’ is more sociably inclined. Give him the village green, just outside the public-house, or a market square on a market day to do his courting in. The ‘Stage Peasant’ has a keen sense of humour and is easily amused. There is something almost pathetic about the way he goes into convulsions of laughter over very small jokes! How a man like that would enjoy a real joke! One day he will, perhaps, hear a real joke. Who knows? It will, however, probably kill him.”

The theatre at that time was in a bad way. The drama had passed through many vicissitudes, but its condition had rarely been so unsatisfactory as it was then. Mr. George Bernard Shaw about this time wrote to

The Nation

: “You can see in many a humble melodrama a brothel on the stage with its procuress in league with the villain, and the bold, bad girl whom he has ruined, all set forth as attractively as possible under the protection of the Lord Chamberlain’s certificate.” The Poet Laureate, Lord Tennyson, also wrote in a letter to Mr. Hall Caine: “The British Drama must be in a low state indeed if, as certain dramatic critics have lately told us, none of the great moral and social questions of the time ought to be touched upon in a modern play.”

Moreover, actors, instead of jealously upholding an honourable professional standard, became demoralized, and tempted by larger salaries, frittered away their talents on trivialities. Jerome always stood for sincerity and honesty; he strongly advocated all that was worthiest in the work of the stage, and as strongly condemned all that was contemptible. He carried these principles into every phase of theatrical activity. Just as Charles Dickens brought about many reforms by means of clever satire, so J. K. J.’s satirical humour had a wholesome effect upon the theatre of his time. For instance, he satirized and trounced unsparingly those managers who indulged in exaggerated puffery; for example:

“‘House Full’ as an advertisement is not good enough. ‘House crammed’ is the legend now displayed. As the art of puffing advances, ‘House crammed’ will soon seem weak, and then we shall probably get such announcements as ‘House crammed to suffocation, men and women fighting for air’. ‘House jammed full — every gangway and exit choked up with people. Three men now dying from suffocation! Four times the number of persons in the theatre than it will safely hold — galleries giving way! Walk up! Walk up!’”

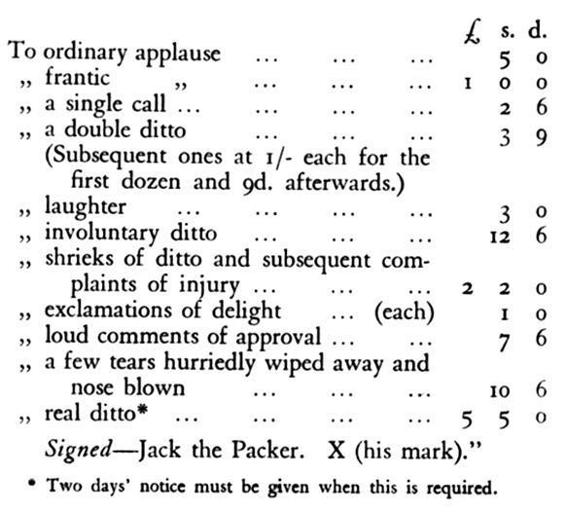

Jerome also recognized a false note in the “Claque” system; that is, the practice of engaging theatre workmen and billposters to applaud the actors, and brought to bear his bantering satire in exposing it; here is a specimen:

“For the convenience of acting managers on first nights, we append a scale of claque charges, corrected up to date: