Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1313 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

After an artillery preparation of considerable intensity, the infantry assault was delivered by the 12th and 13th Royal Sussex of the 116th Brigade. The scheme was that they should advance in three waves and win their way to the enemy support line, which they were to convert into the British front line, while the divisional pioneer battalion, the 13th Gloster, was to join it up to the existing system by new communication trenches. For some reason, however, a period of eleven hours seems to have elapsed between the first bombardment and the actual attack. The latter was delivered at three in the morning after a fresh bombardment of only ten minutes. So ready were the Germans that an observer has remarked that had a string been tied from the British batteries to the German the opening could not have been more simultaneous, and they had brought together a great weight of metal. Every kind of high explosive, shrapnel, and trench mortar bombs rained on the front and support line, the communication trenches and No Man’s Land, in addition to a most hellish fire of machine-guns. The infantry none the less advanced with magnificent ardour, though with heavy losses. On occupying the German front line trenches there was ample evidence that the guns had done their work well, for the occupants were lying in heaps. The survivors threw bombs to the last moment, and then cried, “Kamerad!” Few of them were taken back. Two successive lines were captured, but the losses were too heavy to allow them to be held, and the troops had eventually under heavy shell-fire to fall back on their own front lines. Only three officers came back unhurt out of the two battalions, and the losses of rank and file came to a full two-thirds of the number engaged. “The men were magnificent,” says one who led them, but they learned the lesson which was awaiting so many of their comrades in the south, that all human bravery cannot overcome conditions which are essentially impossible. A heavy German bombardment continued for some time, flattening out the trenches and inflicting losses, not only upon the 39th but upon the 51st Highland Territorial Division. This show of heavy artillery may be taken as the most pleasant feature in the whole episode, since it shows that its object was attained at least to the very important extent of holding up the German guns. Those heavy batteries upon the Somme might well have modified our successes of the morrow.

A second attack made with the same object of distracting the attention of the Germans and holding up their guns was made at an earlier date at a point called the triangle opposite to the Double Grassier near Loos. This attack was started at 9:10 upon the evening of June 10, and was carried out in a most valiant fashion by the 2nd Rifles and part of the 2nd Royal Sussex, both of the 2nd Brigade. There can be no greater trial for troops, and no greater sacrifice can be demanded of a soldier, than to risk and probably lose his life in an attempt which can obviously have no permanent result, and is merely intended to ease pressure elsewhere. The gallant stormers reached and in several places carried the enemy’s line, but no lasting occupation could be effected, and they had eventually to return to their own fine. The Riflemen, who were the chief sufferers, lost 11 officers and 200 men.

A word should be said as to the raids along the line of the German trenches by which it was hoped to distract their attention from the point of attack, and also to obtain precise information as to the disposition of their units. It is difficult to say whether the British were the gainers or the losers on balance in these raids, for some were successful, while some were repelled. Among a great number of gallant attempts, the details of which hardly come within the scale of this chronicle, the most successful perhaps were two made by the 9th Highland Light Infantry and by the 2nd Welsh Fusiliers, both of the Thirty third Division. In both of these cases very extensive damage was done and numerous prisoners were taken.

When one reads the intimate accounts of these affairs, the stealthy approaches, the blackened faces, the clubs and revolvers which formed the weapons, the ox-goads for urging Germans out of dug-outs, the dark lanterns and the knuckle-dusters — one feels that the age of adventure is not yet past and that the spirit of romance was not entirely buried in the trenches of modern war. There were 70 such raids in the week which preceded the great attack.

Before plunging into the huge task of following and describing the various phases of the mighty Battle of the Somme a word must be said upon the naval history of the period which can all be summed up in the Battle of Jutland, since the situation after that battle was exactly as it had always been before it. This fact in itself shows upon which side the victory lay, since the whole object of the movements of the German Fleet was to produce a relaxation in these conditions. Through the modesty of the British bulletins, which was pushed somewhat to excess, the position for some days was that the British, who had won everything, claimed nothing, while the Germans, who had won nothing, claimed everything. It is true that a number of our ships were sunk and of our sailors drowned, including Hood and Arbuthnot, two of the ablest of our younger admirals. Even by the German accounts, however, their own losses in proportion to their total strength were equally heavy, and we have every reason to doubt their accounts since they not only do not correspond with reliable observations upon our side, but because their second official account was compelled to admit that their first one had been false. The whole affair may be summed up by saying that after making an excellent fight they were saved from total destruction by the haze of evening, and fled back in broken array to their ports, leaving the North Sea now as always in British keeping. At the same time it cannot be denied that here as at Coronel and the Falklands the German ships were well fought, the gunnery was good, and the handling of the fleet, both during the battle and especially under the difficult circumstances of the flight in the darkness to avoid a superior fleet between themselves and home, was of a high order. It was a good clean fight, and in the general disgust at the flatulent claims of the Kaiser and his press the actual merit of the German performance did not perhaps receive all the appreciation which it deserved.

Line of battle in the Somme sector — Great preparations — Advance of Forty-sixth North Midland Division — Advance of Fifty-sixth Territorials (London) — Great valour and heavy losses — Advance of Thirty-first Division — Advance of Fourth Division — Advance of Twenty-ninth Division — Complete failure of the assault

THE continued German pressure at Verdun which had reached a high point in June called insistently for an immediate allied attack at the western end of the line. With a fine spirit of comradeship General Haig had placed himself and his armies at the absolute disposal of General Joffre, and was prepared to march them to Verdun, or anywhere else where he could best render assistance. The solid Joffre, strong and deliberate, was not disposed to allow the western offensive to be either weakened or launched prematurely on account of German attacks at the eastern frontier. He believed that Verdun could for the time look after herself, and the result showed the clearness of his vision. Meanwhile, he amassed a considerable French army, containing many of his best active troops, on either side of the Somme. General Foch was in command. They formed the right wing of the great allied force about to make a big effort to break or shift the iron German line, which had been built up with two years of labour, until it represented a tangled vista of trenches, parapets, and redoubts mutually supporting and bristling with machine-guns and cannon, for many miles of depth.

Never in the whole course of history have soldiers been confronted with such an obstacle. Yet from general to private, both in the French and in the British armies, there was universal joy that the long stagnant trench life should be at an end, and that the days of action, even if they should prove to be days of death, should at last have come. Our concern is with the British forces, and so they are here set forth as they stretched upon the left or north of their good allies.

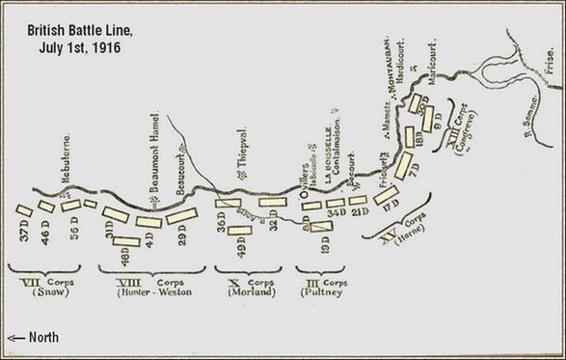

British Battle Line, July 1st, 1916

The southern end of the whole British line was held by the Fourth Army, commanded by General Rawlinson, an officer who has always been called upon when desperate work was afoot. His army consisted of five corps, each of which included from three to four divisions, so that his infantry numbered about 200,000 men, many of whom were veterans, so far as a man may live to be a veteran amid the slaughter of such a campaign. The Corps, counting from the junction with the French, were, the Thirteenth (Congreve), Fifteenth (Horne), Third (Pulteney), Tenth (Morland), and Eighth (Hunter-Weston). Their divisions, frontage, and the objectives will be discussed in the description of the battle itself.

North of Rawlinson’s Fourth Army, and touching it at the village of Hébuterne, was Allenby’s Third Army, of which one single corps, the Seventh (Snow), was engaged in the battle. This added three divisions, or about 30,000 infantry, to the numbers quoted above.

It had taken months to get the troops into position, to accumulate the guns, and to make the enormous preparations which such a battle must entail. How gigantic and how minute these are can only be appreciated by those who are acquainted with the work of the staffs. As to the Chief Staff of all, if a civilian may express an opinion upon so technical a matter, no praise seems to be too high for General Kiggell and the others under the immediate direction of Sir Douglas Haig, who had successively shown himself to be a great Corps General, a great Army leader, and now a great General-in-Chief. The preparations were enormous and meticulous, yet everything ran like a well-oiled piston-rod. Every operation of the attack was practised on similar ground behind the lines. New railheads were made, huge sidings constructed, and great dumps accumulated. The corps and divisional staffs were also excellent, but above all it was upon those hard-worked and usually overlooked men, the sappers, that the strain fell. Assembly trenches had to be dug, double communication trenches had to be placed in parallel lines, one taking the up-traffic and one the down, water supplies, bomb shelters, staff dug-outs, poison-gas arrangements, tunnels and mines — there was no end to the work of the sappers. The gunners behind laboured night after night in hauling up and concealing their pieces, while day after day they deliberately and carefully registered upon their marks. The question of ammunition supply had assumed incredible proportions. For the needs of one single corps forty-six miles of motor-lorries were engaged in bringing up the shells. However, by the end of June all was in place and ready. The bombardment began about June 23, and was at once answered by a German one of lesser intensity. The fact that the attack was imminent was everywhere known, for it was absolutely impossible to make such preparations and concentrations in a secret fashion. “Come on, we are ready for you,” was hoisted upon placards on several of the German trenches. The result was to show that they spoke no more than the truth.

There were limits, however, to the German appreciation of the plans of the Allies. They were apparently convinced that the attack would come somewhat farther to the north, and their plans, which covered more than half of the ground on which the attack actually did occur, had made that region impregnable, as we were to learn to our cost. Their heaviest guns and their best troops were there. They had made a far less elaborate preparation, however, at the front which corresponded with the southern end of the British line, and also on that which faced the French. The reasons for this may be surmised. The British front at that point is very badly supplied with roads (or was before the matter was taken in hand), and the Germans may well have thought that no advance upon a great scale was possible. So far as the French were concerned they had probably over-estimated the pre-occupation of Verdun and had not given our Allies credit for the immense reserve vitality which they were to show. The French front to the south of the Somme was also faced by a great bend of the river which must impede any advance. Then again it is wooded, broken country down there, and gives good concealment for masking an operation. These were probably the reasons which induced the Germans to make a miscalculation which proved to be an exceedingly serious one, converting what might have been a German victory into a great, though costly, success for the Allies, a prelude to most vital results in the future.

It is, as already stated, difficult to effect a surprise upon the large scale in modern warfare. There are still, however, certain departments in which with energy and ingenuity effects may be produced as unforeseen as they are disconcerting. The Air Service of the Allies, about which a book which would be one long epic of heroism could be written, had been growing stronger, and had dominated the situation during the last few weeks, but it had not shown its full strength nor its intentions until the evening before the bombardment. Then it disclosed both in most dramatic fashion. Either side had lines of stationary airships from which shell-fire is observed. To the stranger approaching the lines they are the first intimation that he is in the danger area, and he sees them in a double row, extending in a gradually dwindling vista to either horizon. Now by a single raid and in a single night, every observation airship of the Germans was brought in flames to the earth. It was a splendid coup, splendidly carried out. Where the setting sun had shone on a long German array the dawn showed an empty eastern sky. From that day for many a month the Allies had command of the air with all that it means to modern artillery. It was a good omen for the coming fight, and a sign of the great efficiency to which the British Air Service under General Trenchard had attained. The various types for scouting, for artillery work, for raiding, and for fighting were all very highly developed and splendidly handled by as gallant and chivalrous a band of heroic youths as Britain has ever enrolled among her guardians. The new F.E. machine and the de Haviland Biplane fighting machine were at this time equal to anything the Germans had in the air.

The attack had been planned for June 28, but the weather was so tempestuous that it was put off until it should moderate, a change which was a great strain upon every one concerned. July 1 broke calm and warm with a gentle south-western breeze. The day had come. All morning from early dawn there was intense fire, intensely answered, with smoke barrages thrown during the last half-hour to such points as could with advantage be screened. At 7:30 the guns lifted, the whistles blew, and the eager infantry were over the parapets. The great Battle of the Somme, the fierce crisis of Armageddon, had come. In following the fate of the various British forces during this eventful and most bloody day we will begin at the northern end of the line, where the Seventh Corps (Snow) faced the salient of Gommecourt.

This corps consisted of the Thirty-seventh, Forty-sixth, and Fifty-sixth Divisions. The former was not engaged and lay to the north. The others were told off to attack the bulge on the German line, the Forty-sixth upon the north, and the Fifty-sixth upon the south, with the village of Gommecourt as their immediate objective. Both were well-tried and famous territorial units, the Forty-sixth North Midland being the division which carried the Hohenzollern Redoubt upon October 13, 1915, while the Fifty-sixth was made up of the old London territorial battalions, which had seen so much fighting in earlier days while scattered among the regular brigades. Taking our description of the battle always from the north end of of the the line we shall begin with the attack of the Forty-sixth Division.

The assault was carried out by two brigades, each upon a two-battalion front. Of these the 137th Brigade of Stafford men were upon the right, while the 139th Brigade of Sherwood Foresters were on the left, each accompanied by a unit of sappers. The 138th Brigade, less one battalion, which was attached to the 137th, was in reserve. The attack was covered so far as possible with smoke, which was turned on five minutes before the hour. The general instructions to both brigades were that after crossing No Man’s Land and taking the first German fine they should bomb their way up the communication trenches, and so force a passage into Gommecourt Wood. Each brigade was to advance in four waves at fifty yards interval, with six feet between each man. Warned by our past experience of the wastage of precious material, not more than 20 officers of each battalion were sent forward with the attack, and a proportional number of N.C.O.’s were also withheld. The average equipment of the stormers, here and elsewhere, consisted of steel helmet, haversack, water-bottle, rations for two days, two gas helmets, tear-goggles, 220 cartridges, two bombs, two sandbags, entrenching tool, wire-cutters, field dressings, and signal-flare. With this weight upon them, and with trenches which were half full of water, and the ground between a morass of sticky mud, some idea can be formed of the strain upon the infantry.

Both the attacking brigades got away with splendid steadiness upon the tick of time. In the case of the 137th Brigade the 6th South Staffords and 6th North Staffords were in the van, the former of the being on the right flank where it joined up with the left of the Fifty-sixth Division. The South Staffords came into a fatal blast of machine-gun fire as they dashed forward, and their track was marked by a thick litter of dead and wounded. None the less, they poured into the trenches opposite to them but found them strongly held by infantry of the Fifty-second German Division. There was some fierce bludgeon work in the trenches, but the losses in crossing had been too heavy and the survivors were unable to make good. The trench was held by the Germans and the assault repulsed. The North Staffords had also won their way into the front trenches, but in their case also they had lost so heavily that they were unable to clear the trench, which was well and stoutly defended. At the instant of attack, here as elsewhere, the Germans had put so terrific a barrage between the fines that it was impossible for the supports to get up and no fresh momentum could be added to the failing attack.

The fate of the right attack had been bad, but that of the left was even worse, for at this point we had experience of a German procedure which was tried at several places along the line with most deadly effect, and accounted for some of our very high losses. This device was to stuff their front line dug-outs with machine-guns and men, who would emerge when the wave of stormers had passed, attacking them from the rear, confident that their own rear was safe on account of the terrific barrage between the lines.

In this case the stormers were completely trapped. The 5th and 7th Sherwood Foresters dashed through the open ground, carried the trenches and pushed forward on their fiery career. Instantly the barrage fell, the concealed infantry rose behind them, and their fate was sealed. With grand valour the leading four waves stormed their way up the communication trenches and beat down all opposition until their own dwindling numbers and the failure of their bombs left them helpless among their enemies. Thus perished the first companies of two fine battalions, and few survivors of them ever won their way back to the British lines. Brave attempts were made during the day to get across to their aid, but all were beaten down by the terrible barrage. In the evening the 5th Lincolns made a most gallant final effort to reach their lost comrades, and got across to the German front line which they found to be strongly held. So ended a tragic episode. The cause which produced it was, as will be seen, common to the whole northern end of the line, and depended upon factors which neither officers nor men could control, the chief of which were that the work of our artillery, both in getting at the trench garrisons and in its counter-battery effects had been far less deadly than we had expected. The losses of the division came to about 2700 men.