Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) (1357 page)

Read Delphi Complete Works of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (Illustrated) Online

Authors: SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

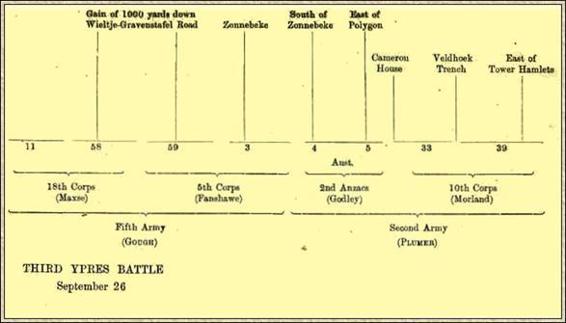

To the right of the Australians the Thirty-third Division went forward also to its extreme objective, gathering up as it went those scattered groups of brave men who had held out against the German assault of the preceding day. This gallant division had a particularly hard time, as its struggle against the German attack upon the day before had been a very severe one, which entailed heavy losses. Some ground had been lost at the Veldhoek Trench north of the Menin road, where the 100th Brigade was holding the line, but this had been partially regained, as already described, by an immediate attack by the First Queen’s West Surrey and 9th Highland Light Infantry. The 2nd Argyll and Sutherlands were still in the front line, but for the second time this year this splendid battalion was rescued from the desperate situation which only such tried and veteran soldiers could have carried through without disaster. Immediately before the attack of September 26, just after the assembly of the troops, the barrage which the Germans had laid down in order to cover their own advance beat full upon the left of the divisional line, near Glencorse Wood, and inflicted such losses that it could not get forward at zero, thus exposing the Victorians, as already recorded. Hence, although the 100th Brigade succeeded in regaining the whole of the Veldhoek Trench upon the right, there was an unavoidable gap upon the left between Northampton Farm and Black Watch Corner. The division was not to be denied, however, and by a splendid effort before noon the weak spot had been cleared up by the Scottish Rifles, the 4th King’s Liverpools, and the 4th Suffolks, so that the line was drawn firm between Veldhoek Trench in the south and Cameron House in the north. A counter-attack by the Fourth Guards Division was crushed by artillery fire, and a comic sight was presented, if anything can be comic in such a tragedy, by a large party of the Guards endeavouring to pack themselves into a pill-box which was much too small to receive them. Many of them were left lying outside the entrance.

Farther still to the right, and joining the flank of the advance, the Thirty-ninth Division, like its comrades upon the left, found a hard task in front of it, the country both north and south of the Menin road being thickly studded with strong points and fortified farms. It was not until the evening of September 27, after incurring heavy losses, that they attained their allotted line. This included the whole of the Tower Hamlets spur with the German works upon the farther side of it. The extreme right flank was held up owing to German strong points on the east of Bitter Wood, but with this exception all the objectives were taken and held by the 116th and 118th, the two brigades in the line. The fighting fell with special severity upon the 4th Black Watch and the 1st Cambridge of the latter brigade, and upon the 14th Hants and the Sussex battalions of the former, who moved up to the immediate south of the Menin road. The losses of all the battalions engaged were very heavy, and the 111th Brigade of the Thirty-seventh Division had to be sent up at once in order to aid the survivors to form a connected line.

The total result of the action of September 26 was a gain of over half a mile along the whole front, the capture of 1600 prisoners with 48 officers, and one more proof that the method of the broad, shallow objective was an effective answer to the new German system of defence by depth. It was part of that system to have shock troops in immediate reserve to counter-attack the assailants before they could get their roots down, and therefore it was not unexpected that a series of violent assaults should immediately break upon the British positions along the whole newly- won line. These raged during the evening of September 26, but they only served to add greatly to the German losses, showing them that their ingenious conception had been countered by a deeper ingenuity which conferred upon them all the disadvantages of the attack. For four days there was a comparative quiet upon the line, and then again the attacks carried out by the Nineteenth Reserve Division came driving down to the south of Polygon Wood, but save for ephemeral and temporary gains they had no success. The Londoners of the Fifty-eighth Division had also a severe attack to face upon September 28 and lost two posts, one of which they recovered the same evening.

Up to now the weather had held, and the bad fortune which had attended the British for so long after August 1 seemed-to have turned. But the most fickle of all the gods once more averted her face, and upon October 3 the rain began once more to fall heavily in a way which announced the final coming of winter. None the less the work was but half done, and the Army could not be left under the menace of the commanding ridge of Paschendaale. At all costs the advance must proceed.

Third Ypres Battle, September 26, 1917

IX. THE THIRD BATTLE OF YPRES

October 4 to November 10, 1917

Attack of October 4 — Further advance of the British line — Splendid advance of second-line Territorials — Good work of H.A.C. at Reutel — Abortive action of October 12 — Action of October 26 — Heavy losses at the south end of the line — Fine fighting by the Canadian Corps — Capture of Paschendaale — General results of third battle of Ypres

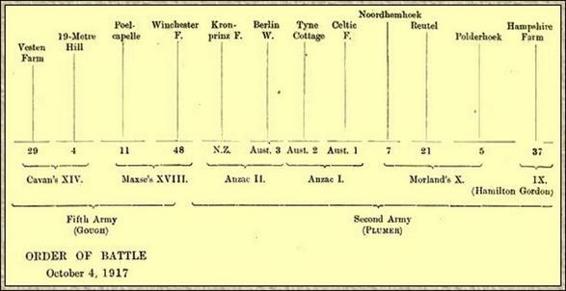

AT early dawn upon October 4, under every possible disadvantage of ground and weather, the attack was renewed, the infantry advancing against the main line of the ridge east of Zonnebeke. The front of Oct. 4 to the movement measured about seven miles, as the sector south of the Menin road was hardly affected. The Ypres-Staden railway in the north was the left flank of the Army, so that the Fourteenth Corps was once more upon the move. We will trace the course of the attack from this northern end of the line.

Cavan’s Corps had two divisions in front — the Twenty-ninth upon the left and the Fourth upon the right, two fine old regular units which had seen as much fighting as any in the Army. The Guards held a defensive flank together with the French between Houthulst Forest and the Staden railway. The advance of the Twenty-ninth was along the line of the railway, and it covered its moderate objectives without great loss or difficulty. Vesten Farm represented the limit of the advance.

The Fourth Division (Matheson) started from a point east of Langemarck and ended from 1000 to

There the Fourth Division lay on their appointed line, strung out over a wide front, crouching in heavy rain amid the mud of the shell-holes, each group of men unable during the day to see or hold intercourse with the other, and always under fire from the enemy. It was an experience which, extended from day to day in this and other parts of the line, makes one marvel at the powers of endurance latent in the human frame. An officer who sallied forth to explore has described the strange effect of that desolate, shell-ploughed landscape, half-liquid in consistence, brown as a fresh-turned field, with no movement upon its hideous expanse, although every crevice and pit was swarming with life, and the constant snap of the sniper’s bullet told of watchful, unseen eyes. Such a chaos was it that for three days there was no connection between the left of the Fourth and the right of the Twenty-ninth, and it was not until October 8 that Captain Harston of the 11th Brigade, afterwards slain, together with another officer ran the gauntlet of the sharp-shooters, and after much searching and shouting saw a rifle waved from a pit, which gave him the position of the right flank of the 16th Middlesex. It was fortunate he did so, as the barrage of the succeeding morning would either have overwhelmed the Fourth Division or been too far forward for the Twenty-ninth. Upon the right of the Fourth Division was the Eleventh. Led by several tanks, the 33rd Brigade upon the left broke down all obstacles and captured the whole of the western half of the long straggling street which forms the village of Poelcapelle.

Their comrades upon the right had no such definite mark before them, but they made their way the right of the Eleventh Division, the 48th South Midland Territorials had a most difficult advance over the marshy valley of the Stroombeek, but the water-sodden morasses of Flanders were as unsuccessful as the chalk uplands of Pozières in stopping these determined troops. Warwicks, Gloucesters, and Worcesters, they found their way to the allotted line. Winchester Farm was the chief centre of resistance conquered in this advance.

To the right of the Midland men the New Zealanders — that splendid division which had never yet found its master, either on battlefield or football ground — advanced upon the Gravenstafel spur. Once more the record of success was unbroken and the full objective gained. The two front brigades, drawn equally from the North and South Islands, men of Canterbury, Wellington, Otago, and Auckland, splashed across the morass of the Hannebeek and stormed their way forward through Aviatik Farm and Boetleer, their left co-operating with the Midlanders in the fall of the Winzic strong point. The ground was thick with pill-boxes, here as elsewhere, but the soldiers showed great resource and individuality in their methods of stalking them, getting from shell-hole to shell-hole until they were past the possible traverse of the gun, and then dashing, bomb in hand, for the back door, whence the garrison, if they were lucky, soon issued in a dejected line. On the right, the low ridge magniloquently called “Abraham’s Heights” was carried without a check, and many prisoners taken. Evening found the whole of the Gravenstafel Ridge in the strong hands of the New Zealanders, with the high ruin of Paschendaale Church right ahead of them as the final goal of the Army.

These New Zealanders formed the left unit of Godley’s Second Anzac Corps, the right unit of which was the Third Australian Division. Thus October 4 was a most notable day in the young, but glorious, military annals of the Antipodean Britons, for, with the First Anzac Corps fighting upon the right, the whole phalanx made up a splendid assemblage of manhood, whether judged by its quality or its quantity. Some 40,000 infantry drawn from the islands of the Pacific fronted the German and advanced the British line upon October 4. Of the Third Australians it can only be said that the showed themselves to be as good as their comrades upon either flank, and that the attained the full objective which had been marked as their day’s work. By 1:15 the final positions had been occupied and held.

Gravenstafel represents one end of a low eminence which stretches for some distance. The First and Second Australian Divisions, attacking upon the immediate right of the Second Anzac Corps, fought their way step by step up the slope alongside of them and established themselves along a wide stretch of the crest, occupying the hamlet of Broodseinde. This advance took them across the road which leads from Bacelaer to Paschendaale, and it did not cease until they had made good their grip by throwing out posts upon the far side of the crest. The fighting was in places very sharp, and the Germans stood to it like men. The official record says: “A small party would not surrender. It consisted entirely of officers and N.C.O.’s with one medical private. Finally grenades drove them out to the surface, when the Captain was bayoneted and the rest killed, wounded, or captured. One machine-gunner was bayoneted with his finger still pressing his trigger.” Against such determined fighters and on such ground it was indeed a glory to have advanced

Order of Battle, October 4, 1917

On the immediate right of the Australians was Morland’s Tenth Corps, with the Seventh, Twenty-first, and Fifth Divisions in the battle line. The Seventh Division had stormed their way past a number of strongholds up the incline and had topped the ridge, seizing the hamlet of Noordhemhoek upon the other side of it. This entirely successful advance, which maintained the highest traditions of this great division, was carried out by the Devons, Borderers, and Gordons of the 20th Brigade upon the left, and by the South Staffords and West Surreys of the 91st Brigade upon the right. The full objectives were reached, but it was found towards evening that the fierce counter-attacks to the south had contracted the British line in that quarter, so that the right flank of the 91st Brigade was in the air. Instead of falling back the brigade threw out a defensive line, but none the less the salient was so marked that it was clear that it could not be permanent, and that there must either be a retirement or that some future operation would be needed to bring up the division on the right.

To the right of Noordhemhoek the Twenty-first Division had cleared the difficult enclosed country to the east of Polygon Wood, and had occupied the village of Reutel, but encountered such resolute opposition and such fierce counter-attacks that both the advancing brigades, the 62nd and the 64th, wound up the day to the westward of their full objectives, which had the effect already described upon the right wing of the Seventh Division. Both front brigades had lost heavily, and they were relieved in the front line by the 110th Leicester Brigade of their own division. During the severe fighting of the day the losses in the first advance, which gained its full objectives, fell chiefly upon the 9th Yorkshire Light Infantry. In the second phase of the fight, which brought them into Reutel, the battalions engaged were the 8th East Yorks and 12th Northumberland Fusiliers, which had to meet a strong resistance in difficult country, and were hard put to it to hold their own. The German counter-attacks stormed all day against the left of the line at this point around Reutel, making the flanks of the Fifth and Seventh Divisions more and more difficult, as the defenders between them were compelled to draw in their positions. A strong push by the Germans in the late afternoon got possession of Judge Copse, Reutel, and Polderhoek Château. The two former places were recovered in a subsequent operation.

On the flank of the main attack the old Fifth Division, going as strongly as ever after its clear three years of uninterrupted service, fought its way against heavy opposition up Polderhoek Château. The Germans were massed thickly in this quarter and the fighting was very severe. The advance was carried out by those warlike twins, the comrades of many battles, the 1st West Kents and 2nd Scots Borderers upon the right, while the 1st Devons and 1st Cornwalls of the 95th Brigade were on the left, the latter coinciding with the edge of Polygon Wood and the former resting upon the Menin road. The 13th actually occupied Polderhoek Château, but lost it again. The 95th was much incommoded by finding that the Reutelbeek was now an impassable swamp, but they swarmed round it and captured their objectives, while its left got beyond Reutel, and had to throw back a defensive flank on its left, and withdraw its front to the west of the village. The chief counter-attacks of the day were on the front of the Fifth and Twenty-first Divisions, and they were both numerous and violent, seven in succession coming in front of Polderhoek Château and Reutel. This fierce resistance restricted the advance of Morland’s Tenth Corps and limited their gains, but enabled them to wear out more of the enemy than any of the divisions to the north.

Upon the flank of the attack, the advance of the Thirty-seventh Division had been a limited one, and had not been attended with complete success, as two of the German strongholds — Berry Cottages and Lewis House — still held out and spread a zone of destruction round them. The 8th Somersets, 8th Lincolns, and a Middlesex battalion of the 63rd Brigade all suffered heavily upon this flank. On the northern wing the 13th Rifles, 13th Rifle Brigade, and Royal Fusiliers of the 111th Brigade drove straight ahead, and keeping well up to the barrage were led safely by that stern guide to their ultimate positions, into which they settled with a comparative immunity from loss, but the battalions were already greatly exhausted by long service and scanty drafts, so that the 13th Rifles emerged from the fight with a total strength of little over a hundred. It must be admitted that all these successive fights at the south of the Menin road vindicated the new German systems of defence and caused exceedingly heavy losses which were only repaid by scanty and unimportant gains of desolate, shell-ploughed land.

The total result of this Broodseinde action was a victory gained under conditions of position and weather which made it a most notable, accomplishment. Apart from the very important gain of ground, which took the Army a long way towards its final objective, the Paschendaale Ridge, no less than 138 officers and 5200 men were taken as prisoners. The reason for this considerable increase in captures, as compared to recent similar advances, seems to have been that the Germans had themselves contemplated a strong attack upon the British line, especially the right sector, so that no less than five of their divisions had been brought well up to the front line at the moment when the storm burst. According to the account of prisoners, only ten minutes intervened between the zero times allotted for the two attacks. The result was not only the increase in prisoners, but also a very high mortality among the Germans, who met the full force of the barrage as well as the bayonets of the infantry. In spite of the heavy punishment already received, the Germans made several strong counter-attacks in the evening, chiefly, as stated, against the hues of the Fifth and Twenty-first Divisions north of the Menin road, but with limited results. An attack upon the New Zealanders north of the Ypres-Roulers railway had even less success. Victorious, and yet in the last extremity of human misery and discomfort, the troops held firmly to their advanced line amid the continued pelting of the relentless rain.