Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) (425 page)

Read Delphi Works of Ford Madox Ford (Illustrated) Online

Authors: Ford Madox Ford

CONTENTS

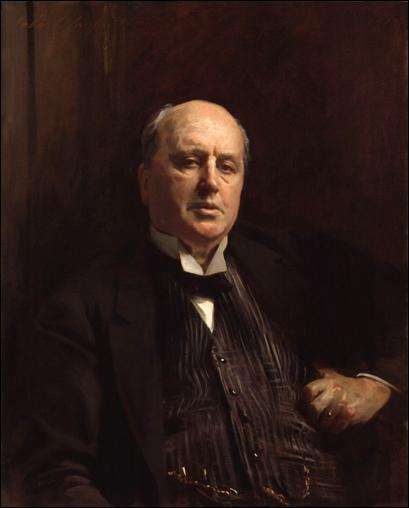

Portrait of Henry James by John Singer Sargent, 1913

DEDICATION

Dear Miss Ada Potter,

Since it was historic tragedy which, as you might say, brought us together, accept the dedication of this very unhistoric comedy for which you are so largely responsible

.

Why it should have come into your head to inspire me to a task obviously so frivolous and one which will draw down upon my head the reprehensions of the great and serious and the stern disapproval of eminent and various critics, is a matter that lies between yourself and your conscience. But I suppose, in this odd, frequently unpleasant and almost always much too serious world, even a person so earnest as yourself feel-s the desire to be made to laugh by an historian so obviously earnest as I am.

Accept therefore the full responsibilities of this attempt to satisfy your demand in the spirit which dictates the offer and believe me,

Your humble obliged and obedient Servant

MAJOR EDWARD BRENT FOSTER was buying illustrated papers at the bookstall on the main line departure platform of Waterloo Station. He had under his arm a whole sheaf of these for which he had not yet paid, and he was looking at the novels that, in a bright-coloured wall, rose up before his dim eyes, when his tired glance wandered towards the entrance from the booking-office. He exclaimed:

“Oh, my aunt!” For, in spite of his shortsightedness, he had perceived Mrs. Kerr Howe, with whom four years before he had been almost too familiar, and he moved swiftly but circumspectly down the platform. He kept, indeed, an eye over his shoulder whilst he attempted to hum nonchalantly, and he was aware that Mrs. Kerr Howe was undoubtedly following him. He walked more swiftly — under the passenger bridge, past another railway bookstall, past the railway barber’s and the railway gimcrack shop. He was, indeed, almost in the passage that leads to the South Eastern line, and he was wondering if he would ever be able to stop before he reached Tonbridge or even Calais. Then he ran against a quite girlish figure in very white muslins who had following her a porter burdened with four sorts of dressing-cases. She exclaimed:

“Teddy

Brent!

” And Major Brent Foster could not help ejaculating:

“Oh, my uncle!” since these relatives were really in his mind. For this was Miss Flossie Delamare, with whom, three years before, he had been almost more familiar.

She was fair and quite happy, and if her features showed traces of having been overpowdered professionally, there was not any doubt that she still had a complexion to lose. And she was so pleasantly glad to see him that Major Brent Foster took a desperate resolve. He had slewed round to face her, and he was aware out of the corner of his eye that Mrs. Kerr Howe was hovering a little way away.

“You’ve got to save me, Flossie,” he said quickly and humorously. “An awful past is after me. I’m not Teddy Brent any more, and I am a reformed character.”

Miss Delamare took on a slightly injured — nay, it occurred to him that it was a very hurt air.

“Oh, well, Teddie,” she said, “I’m not part of your awful past! If you don’t want to be Teddy Brent to me, you can be the Reverend Jonas Whale, though it’s not like you, Teddy.”

He was aware that Mrs. Kerr Howe, brought up by this conversation, was moving regretfully back to the main line platform.

“Oh, keep talking, Flossie darling!” he exclaimed. “Keep talking! The cloud’s rolling by! I am a reformed character — but it’s rolling by.”

“Teddy,” she said, “I don’t believe you need — that you ever needed to be a reformed character.”

“Oh, but I am,” he asseverated, with an air that was partly earnest and partly humorous. “I don’t drink when anybody’s looking, and only between meals, anyhow. And I don’t smoke when anyone can smell it. And as for... that sort of thing...” She said, “Well?” interestedly.

“Oh, well,” he sighed, “of course there’s Olympia — Olympia Peabody that I’m engaged to. And that doesn’t leave any smell. I mean...”

“You mean,” she said, “that it does not matter — who’s looking or whether it’s between meals or at them. And it’s not much fun. And we’re all getting older and wiser.... That sort of disagreeable thing.... Now, at Simla... at Simla...” She suddenly turned upon her porter. “Look here,” she exclaimed, “I shall miss my train. Go and put my things in a first — an empty first smoker. I want to be alone. Tell the guard, Miss Flossie Delamare... he’ll know.”

The porter said, “Yes, miss,” and lurched away beneath all her dressing-cases.

“And you... you’re as famous as all that?” he asked.

“As all what?” she said.

“That every guard knows your name?”

“Oh, is that all?” she said. “Why, every Anabaptist minister knows my name.”

Major Brent Foster raised his eyebrows interrogatively. 11 Anabaptist?” he asked.

“Oh, particularly!” she said. “I’ve been causing trouble in that camp.”

Conscious of a minute pang of something resembling jealousy, he said: “Of course, you would cause trouble in that camp. Now, I’ve got an uncle who’s an Anabaptist — a Post Anabaptist....”

“My old Johnnie’s a Post Anabaptist, too,” Miss Delamare said.

“Well, that’s all right, that’s all right,” Major Brent Foster exclaimed touchily. “Those are your private affairs. I’ve got to catch my train,” and he moved off towards the platform. She walked beside him.

“You know, Teddy,” she said rather plaintively, “you’re very funny to-day. You’re not a bit like your old Irish self. You’re not a bit even like a gentleman.”

“Oh, hang it all!” he exclaimed. “No, I’m not a bit like my old Irish self. I’m not even a gentleman. I tell you I’m a reformed character.” She opened resignedly her immense reticule, which was made of brown canvas sewn over with silver lace, black pearls, and red coral. She produced a large white card.

“Oh, well, Teddy,” she said, “here’s my address. Come and see me one day next week.”

He gave a start back as if the card had been red hot.

“My God, no!” he exclaimed. “I shall be in the country all next week. I never call on anybody. I shut myself up. I work, I tell you. I read the complete works of Henry James. That’s why I’m the youngest major in the British Army.”

“Oh, well, Teddy,” she said, “you’re very funny. Almost as funny as you used to be in the old days. Only in another way. Don’t you remember Simla... and the pukka drives?... Don’t look so miserable!

I’m

not your awful past. I’m not going to upset Miss Olympia Peabody. I guess that’s your awful past waiting for you under the foot-bridge.”

He gave an agitated glance towards those shadows. Sure enough, though to him she was nothing but a blur of gay colours, beneath the foot-bridge, there was the emerald-green tulle dust-cloak and the immense black hat with the pink roses of Mrs. Kerr Howe.

Major Brent Foster clutched the wrist of Miss Delamare.

“Oh, stop with me, Flossie,” he said; “stop with me! She won’t come near me while you are here.”

“I’ll stop with you,” she said. “I’ll stop with you as long as you like, old boy. That’s to say, I’m travelling by the 6.48, so I shall have to leave you and cut at 6.46.”

“I’m travelling by the 6.48, too,” he answered; and then he exclaimed: “Look here, Flossie, Mrs. Kerr Howe isn’t really my awful past. I haven’t got an awful past at all. Only a damned beastly unpleasant past. Dust and ashes — that’s what has crocked up my poor eyes — and alkali wells in Somaliland.”

Miss Delamare said rather viciously: “Oh, we always knew, even in Simla, that it had got its little girl waiting for it with trusting eyes in a little parsonage. But we didn’t know that its little girl’s little name was Olympia. I shouldn’t care to waste twelve years — not for an Olympia. I’d have my little horse show in between the big meetings.”

“I don’t in the least understand you,” Major Brent Foster said.

“Of course, you wouldn’t!” she said. “Being so long out of England and studying for the Staff College Exam, and all.”

“What I want you to understand,” he answered, “is that Mrs. Kerr Howe is not an awful past. She’s just a burr. She’s a sticker. That’s what she is. And as she is got up in pink and green, and her husband’s been dead eighteen months, it’s a sign that she’s dangerous.”

“Well, I seem to be dangerous, too,” Miss Delamare said plaintively.

“Oh, you’re dangerous in another way,” Major Brent Foster said earnestly. “Don’t you see, she’s a black draught: you’re a little spoonful of jam. That’s the difference. She’s remorse: you’re temptation. That’s the difference, too.”

“Well now, Teddy, that’s decent of you,” she said. “I’ll forgive you miles and miles for that — and leave you to your Olympia.”

She looked up the platform; they were standing in front of the other bookstall, just near the gimcrack shop.

“Mrs. Kerr Howe,” she said, “seems to have given up the game, so I can go and find my seat. Of course, it’s a privilege to have been allowed to gaze on Mrs. Kerr Howe even from a distance.”

“Why the devil should it be?” he asked.

“Well, you did entertain angels unawares — in Simla,” she mocked at him. “There you had me — and ain’t I the top notch of musical comedy? And there you had Mrs. Kerr Howe, and isn’t she the greatest and most popular novelist the world has ever seen?”

“I didn’t know,” Major Brent Foster said innocently; “but, of course, I’m awfully glad, Flossie. You used to be rather a starved little rat — in Simla.”

“So I was, Teddy,” she said, “and you were pretty good to me. I shan’t forget it. Good-bye, old Teddy. I expect you’ll be a sidesman and take round the plate before we meet again.”

She moved away up the platform, and Major Brent Foster remained looking at the bookstall. The name “Juliana Kerr Howe” met his eye at least twenty-seven times. There was

Pink Passion

, by Juliana Kerr Howe, with the picture of a lady in a pink nightgown. There was

All for Love

, by Juliana Kerr Howe, with the gilt design of a pierced heart and a broken globe on the cover. There was a lady’s weekly periodical with the inscription in purple letters, “The Lonely Girl. Read about her inside. By Juliana Kerr Howe.”

Major Brent Foster exclaimed “My God!” in an appalled manner. Then he suddenly attacked the small boy who was sitting behind the stall.

“Do you mean to say,” he said, and in his agitation the trace of an Irish accent became audible in his voice, “do you mean to say that you haven’t got a single book of James’?”

“Never heard the name,” the bookstall boy said. “But there’s plenty by Mrs. Kerr Howe.”

“That kelch!” Major Foster exclaimed. “I tell you, it was reading the books of James that made me the youngest major in the British Army. You tell all your customers that.”

And then extraordinary things happened to Major Brent Foster. It began with the soft, crawling voice of Mrs. Kerr Howe that exclaimed at his elbow:

“Captain Edward Brent!”

He spun round and exclaimed: “Mrs. Kerr Howe by all that’s wonderful! I was just buying

all

your books!”

And almost simultaneously he heard from behind his back the voice of Miss Flossie Delamare saying plaintively, “Teddy

dear

, there’s something I want to say to you. I don’t want you to think I am any worse than I am.”

There was also the gruff voice of the clerk at the first bookstall remarking:

“You haven’t paid for them magazines.”

Major Brent Foster spun round on his heel once more. Mrs. Kerr Howe walked frostily up the platform, and Miss Delamare gazed after her with spiteful glee.

“I’m watching over you, Teddy, all right!” she laughed. “I watched that cat of a woman. She was hiding on the other side of the steps of the bridge. And the moment she saw me leave you she sailed down. Did you see her draw her skirts together as I came up? She was afraid I was going to defile her. Her! Who writes books called

A Maid and No Maid.

I should be ashamed!”

“You’re a regular brick,” Major Foster exclaimed. They had walked a little way from the bookstall. The voice of the first clerk came in a sort of chorus:

“You haven’t paid for them magazines. Three and fourpence.”

“Not but what,” Miss Delamare continued, “I wasn’t speaking the truth when I said that I had something to tell you. It’s true that I don’t want to let you think that I am worse than I am. Now this old Johnnie — this Anabaptist that I was speaking of. I don’t want you to think — to think that I’m.. — she brought it out—”living with him.”

“Three and fourpence,” the bookstall clerk remarked. “You come to my stall, and you took three and fourpence worth of papers and you never paid for them.”

“Oh, go away!” Major Brent Foster exclaimed, and he pushed his elbow into the bookstall clerk’s chest. He continued to Miss Delamare: