Desert Divers (7 page)

Authors: Sven Lindqvist

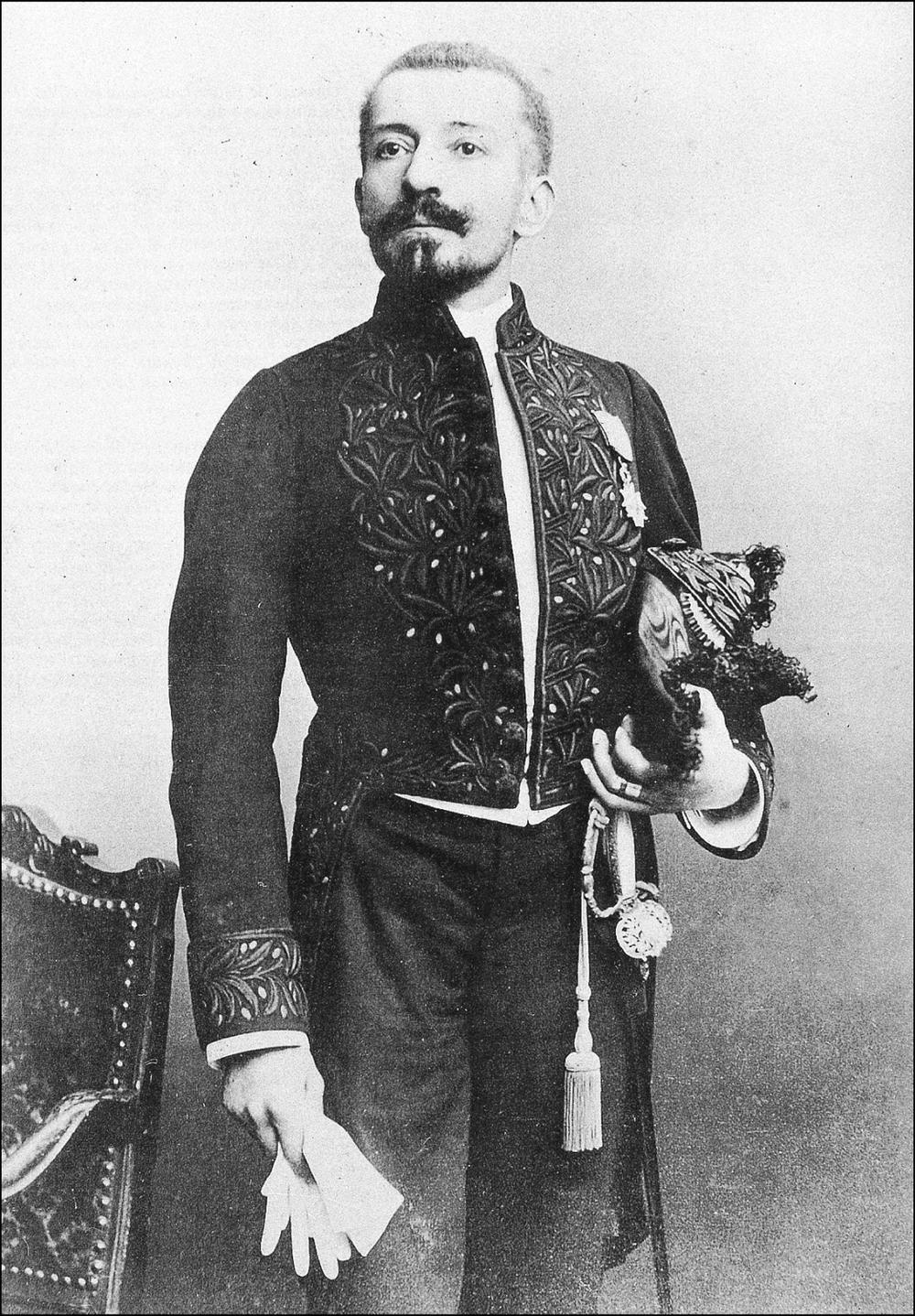

Loti as a naval officer. (

House of Pierre Loti, Rochefort, France

)

Loti as the goddess Osiris. (

House of Pierre Loti, Rochefort, France

)

With a certain satisfaction, I regard the body I have created with my exercises. The muscles stand out in relief in the close-fitting costume. An old juggler elevates the effect by lightly shading in the contours of my muscles with a pencil. This strange anatomical toilet takes twenty minutes.

Even in his nakedness he has to disguise himself. He dyes his moustache and rouges his cheeks; he sits in the French Academy made up like an old whore – hoping no one will see how small he is.

He loves his way through the world, conquering it in the form of women. Asia, Africa, the South Seas and the Atlantic, the deserts of Sahara, Sinai and Persia – he has been everywhere, he has skimmed the romanticism off existence and taken it back with him into his art and home.

In his doll’s house, the world at last is given its correct proportions. Inside it, he is large.

A moon-pale and determined young woman has been given an assignment by the French Academy to free Pierre Loti from his enchanted house. The Academy Action Group arrives in a helicopter and those most immortal climb down rope ladders onto the roof of the mosque. They search through the house without finding Loti. ‘Search thoroughly,’ says Isabelle. ‘He’s always in disguise.’ But they find nothing but a little dog which she takes in her arms as she climbs up into the roaring

helicopter, its rotor blades making the roof tiles jump. The dog is a small black and white Scottie with a bristly moustache and yearning eyes. One of its hind legs is rather stiff from being almost constantly raised. It also carries its nose very high.

‘You can see it’s Pierre Loti’s dog,’ says Isabelle. Then the disguise suddenly falls away and little Loti is standing there with his nose in the air – without his dog-mask, but strangely dog-like all the same.

More people drown in the desert than in the sea. They drown from lack of imagination. They simply cannot imagine enough water to drown in.

An

oued

is a dried-out river channel. But it could be thousands of years since any river flowed there, so it is more correct to say that an

oued

is the track left by torrents that have passed by. The desert is full of tracks of that kind, and you can live a whole life without ever seeing them filled with water. It is like living by the main line south without ever seeing a single train. Gradually you begin to think none will come. And if the whole landscape is a shunting-yard full of similar railway lines where no trains run, either – well, then you finally feel absolutely safe.

When the express train comes thundering along one night in accordance with some unknown timetable, you are not prepared. The torrent suddenly roars through and drowns everything in its path.

It came to Ain Sefra on the night of October 21, 1904.

I admit that I cross the

oued

in Ain Sefra with some haste. I can see bits of skeleton in the sand on the other side. And further up, whole corpses of sheep, goats and cattle – swept down by a tidal wave? Or is it a kind of animal cemetery?

I come to a forest planted to bind the dunes. A shepherd is reading a book there.

‘Sidi Bou Djema?’ I say, in monosyllables.

He points to the faint outline of a wall on top of a dune and replies equally monosyllabically:

‘Sidi Bou Djema!’

But when I get up there, it is just a wall enclosing a small garden where a lone man and his dog grow chickpeas and onions.

The man is very friendly and he speaks beautiful French. He knows exactly where the tomb is and is pleased to take me there.

It is his garden. He laid it out himself. He dug the well himself, eleven metres deep. He fired the clay bricks for the wall himself. It would have been ready by now if it hadn’t rained the other day. His semi-fired bricks have run out into the ground – look at this! Now he has to start all over again. He is used to that. He was a guest-worker in France for eight years and has worked in Marseilles and Lyons. He has even been to Paris. Now he has come back, has a wife and six children, five of them boys, and he is looking forward to a secure old age when he no longer needs to do any work, other than potter around in his garden.

As he is telling me this, we have got as far as the burial ground of Sidi Bou Djema. It lies with dunes and mountains behind it and a view over the

oued

where it happened.

A few spindly stems of grass grow in the sand after the rain. But all the same, it is a very desolate place. The desolation seems to be concentrated on the absurd buckled aluminium saucepan hanging at the back of a tombstone. On the front it says in European letters:

54

The act of departure is the bravest and most beautiful of all. A selfish happiness perhaps, but it is happiness – for him who knows how to appreciate it. To be alone, to have no needs, to be unknown, a stranger and at home everywhere and to march, solitary and great, to the conquest of the world …

That is what Isabelle Eberhardt writes in a piece sometimes called ‘The Road’, sometimes ‘Notes in Pencil’.

Departure is a tradition in her family. Her surname comes from her German maternal grandmother, Fräulein Eberhardt, who left her country to live with a Russian Jew.

Her mother marries an old Russian general, but then leaves him to go to Geneva with the children’s young tutor – a handsome, intellectual Armenian, Tolstoy’s apprentice, Bakunin’s friend. He has been a priest, is married and now leaves his wife and children to live with his beloved in exile.

He teaches Isabelle six languages: French, Russian, German, Latin, Greek and Arabic. But he never admits to her face that he is her father.

She grows up among exiled anarchists in a chaotic milieu in which catastrophe is the natural state.

When she is eight, her brother Nicholas joins the Foreign Legion.

When she is nine, her sister Olga runs away and marries against the will of her family.

When she is seventeen, her favourite brother Augustin joins the Foreign Legion.

When she is twenty, she goes with her mother to Algeria. They both convert to Islam. The mother dies and is buried in Annaba.

When she is twenty-one, her brother Vladimir commits suicide.

When she is twenty-two, she gives her father, who is dying of cancer, an overdose of a pain-killing drug which, intentionally or not, ends his life.

She is alone in the world. At the turn of the century in 1900 she writes in her diary that the only form of bliss, however bitter, destiny will ever grant her is to be a nomad in the great deserts of life.

In secret, my sister Isabelle winds wet cotton bandages round her chest. She wears these bandages under her clothes and

with not the slightest sign betrays what is going on. Only I know about it and I cannot stop her. She winds the wet bandages tightly, tightly round her chest. When they dry and shrink, they slowly crush her chest and suffocate her heart. No one can save her.

‘From where have I got this morbid craving for barren ground and desert wastes?’ Isabelle Eberhardt asks.

In her teens, she was charmed by the melancholy escapism of Loti’s first novel

Aziyadé

, and he became her favourite author. When his

The Desert

came out in 1895, she was eighteen years old. Two years later she set out into the desert on her own for the first time. Loti was the one she always took with her on her journeys, the only person she looked up to as a forerunner and example.

She thought she had found her soulmate. He had a beloved older brother who had gone to sea, she has a beloved older brother who became a legionnaire. Her life, like his, is shrouded in departure and loss. Both live in disguise. And both love the desert, where they see their emptiness and their longing for death take shape.

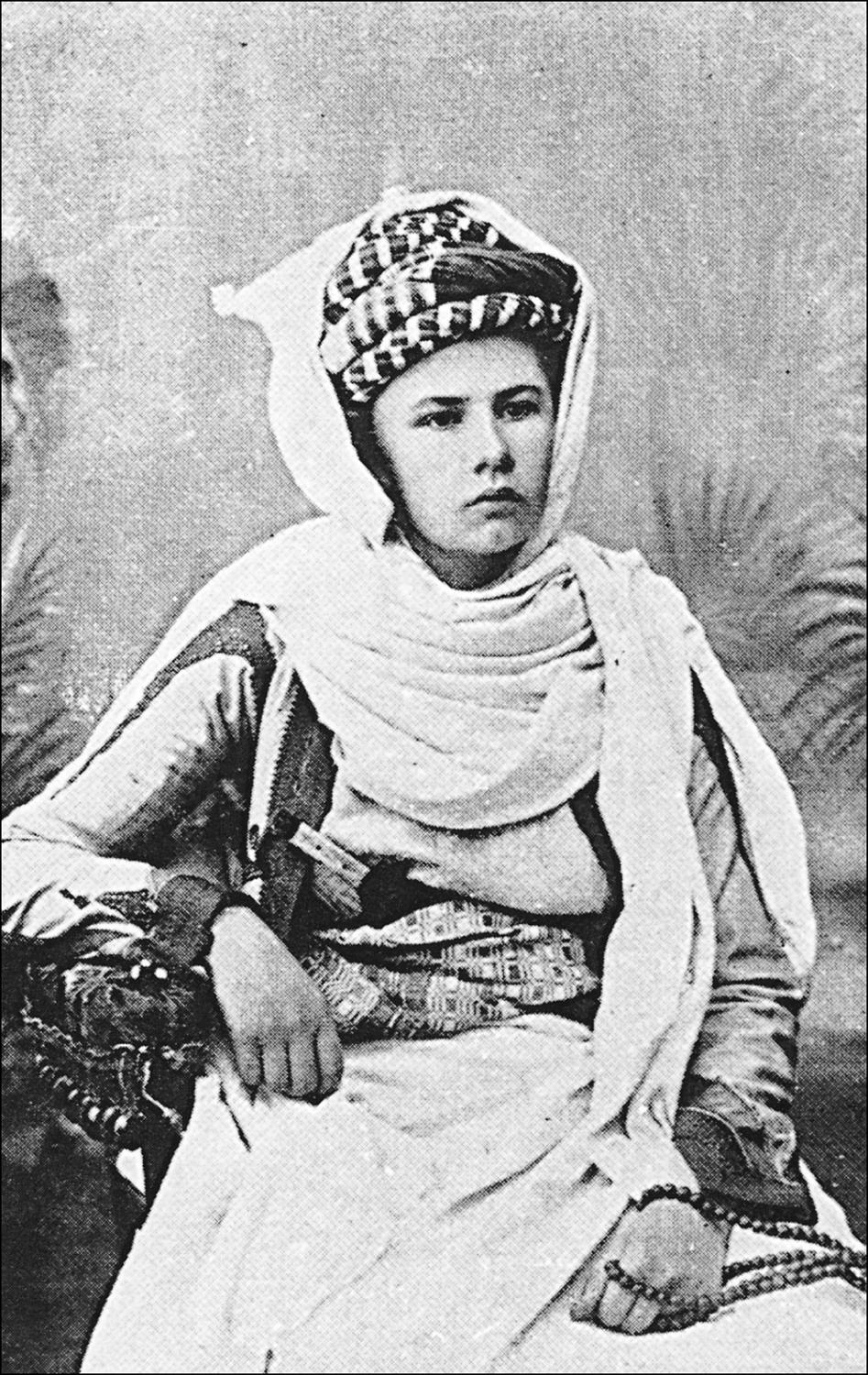

Eberhardt as a Bedouin.

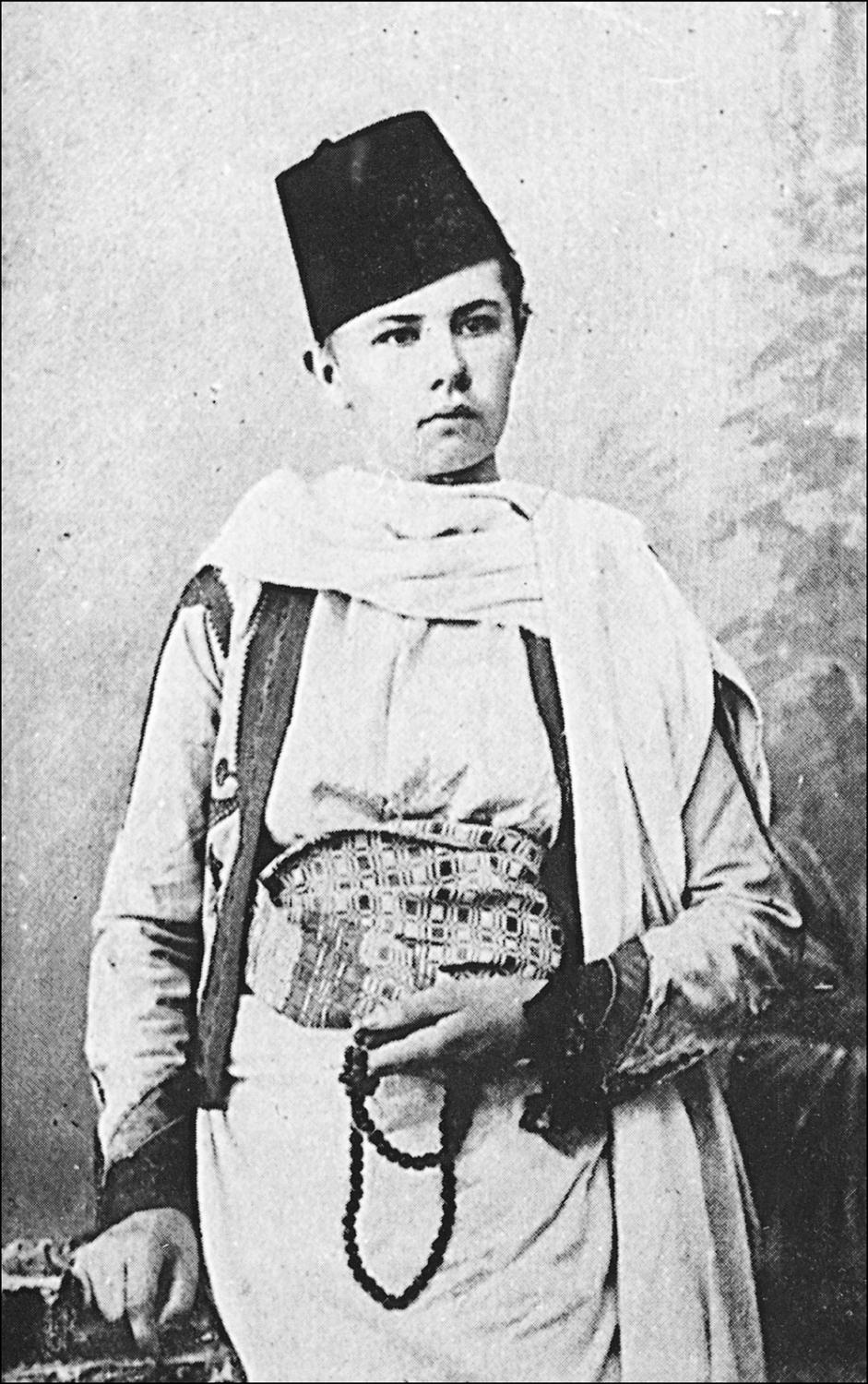

Eberhardt as a spahi.

Michel Vieuchange set off into the desert disguised as a woman. Isabelle sets off into the desert disguised as a man.

To her it is not just a disguise. The French language mercilessly reveals whether the writer considers him- or herself to be a man or a woman. Even in her diary Isabelle uses the masculine to describe herself.

Pierre Loti disguised himself as an Arab, but also as a Chinese, a Turk and a Basque. In every harbour, in every book, he takes on a new disguise. He became a cut-out doll for ever in new costumes, a cultural chameleon melting into every environment and lacking authenticity wherever he went.

The disguise goes deeper in Isabelle. When she returns to Africa, she wants to free herself from her past and take on a new and Arab identity. She becomes the Tunisian author Si Mahmoud Essadi.

Dressed in the clothes of an Arab man, she sets off into the desert. She has been waiting for this moment all her life. She rides between the oases with a few native cavalrymen, with a group of legionnaires, with a

chaamba

caravan, with an African on his way home to his village to get a divorce. She writes:

Now I am a nomad – with no other homeland than Islam, with no family, no one in whom to confide, alone, alone for ever in the proud and darkly sweet solitude of my own heart …

She soon finds a separate confidant in one of her Arab lovers. Slimene Ehni is a sergeant in the native cavalry. She meets

him in El Oued and through him becomes a member of a Sufi community, which is secretly opposed to French rule.

Another Arab fraternity closer to the French tries to murder her. A stretched washing line softens the blow and saves her life.

The French army banish her from North Africa and she ends up in Marseilles, where she supports herself for a while by writing letters in Arabic for the guest-workers.

Slimene also goes there, and on October 17, l901, they marry. By marrying an Arab in the service of France, she becomes a French citizen and can return to the desert.

With Slimene she rents a small house in Ain Sefra, which is the headquarters of the French troops during the ‘pacification’ of the border with Morocco.