Dickens' Women (6 page)

Authors: Miriam Margolyes

Â

When the original Miss Mowcher (Mrs Seymour-Hill) read that episode of

David Copperfield

she was mortified. She wrote angrily to Dickens: âall know you have drawn my portrait â I admit it but the vulgar slang of language I deny.'

Dickens had not meant to hurt her and for once his

compassion

overcame his genius. He wrote to her lawyer apologising and offered âto alter the whole design of the character'. He did â and the next time Miss Mowcher appears in the novel, she's a completely different character â utterly saintly and very boring â so I shan't do her!

A woman's portrait â startling in its modernity â is the lesbian, Miss Wade, from

Little Dorrit

â making no apologies for anything.

Little Dorrit

, 1855â57

âI have the misfortune of not being a fool. From a very early age I have detected what those about me thought they hid from me. My childhood was passed with a grandmother; that is to say, with a lady who represented that relative to me, and who took that title on herself; she had no claim to it.

âShe had some children of her own family in the house, and some children of other people. All girls; ten in number including me. We all lived together and were educated together. I must have been about twelve years old when I began to see how

determinedly

those girls patronised me.

Miss Wade â Sol Eytinge, 1867

âOne of them was my chosen friend. I loved that stupid mite in a passionate way that she could no more deserve than I can remember without feeling ashamed of, though I was but a child.

âShe had what they called an amiable temper, an affectionate temper. She could distribute, and did distribute, pretty looks and smiles to every one among them. I believe there was not a soul in the place, except myself, who knew that she did it purposely to wound and gall me! Nevertheless, I so loved that unworthy girl that my life was made stormy by my fondness for her. I loved her faithfully; and one time I went home with her for the holidays.

âShe was worse at home than she had been at school. She had a crowd of cousins and acquaintances, and we had dances at her house, and went out to dances at other houses, and both at home and out, she tormented my love beyond endurance.

âHer plan was to make them fond of her â and so drive me wild with jealousy.

âWhen we were left alone in our bedroom at night I would reproach her with my perfect knowledge of her baseness; and then she would cry and cry and say I was cruel, and then I would hold her in my arms 'til morning: loving her as much as ever, and often feeling as if, rather than suffer so, I could so hold her in my arms and plunge to the bottom of a river â where I would still hold her after we both were dead.'

Â

You see, he is such an extraordinary writer: he can create a woman like that with such power and truth and understanding I think, and yet, at the same time be such a male chauvinist that if he hadn't made us laugh so much when we were researching this, he'd have made us very angry.

This, for example, is his perfect wife â Mrs Chirrup from

Sketches for Young Couples

.

Music

.]

Mrs Chirrup,

Sketches for Young Couples

, 1840

Mrs Chirrup is the prettiest of all little women and has the

prettiest

little figure conceivable. She has the neatest little foot, and the softest little voice, and the pleasantest little smile, and the tidiest little curls, and the brightest little eyes, and the quietest little manner, and is, in short, altogether one of the most engaging of all little women, dead or alive.

She is a condensation of all the domestic virtues â a pocket edition of the Young Man's Best Companion â a little woman at a very high pressure, with an amazing quantity of goodness and usefulness in an exceedingly small space.

But if there be one branch of house-keeping in which she excels⦠it is in the important one â of carving!

Charles Dickens married Catherine Hogarth in 1836 and the most extraordinary thing about the marriage was its ending.

A friend of theirs, Henry Morley, described her:

Dickens has evidently made a comfortable choice. Mrs Dickens is stout, with a round, very round, rather pretty, very pleasant face, and ringlets on either side of it. One sees in five minutes that she loves her husband and her children and has a warm heart for anyone who won't be satirical, but meet her on her own good-natured footing.

Anyone who won't be satirical!

Well, the years went by, and the children kept coming â twelve births in sixteen years. Catherine grew older and stouter and clumsier. Dickens wrote in 1842, âCatherine is as near being a donkey as one of her sex can be.'

And Harriet Martineau, a noted feminist of the time, who

came to stay with them, wrote: âDickens has terrified and depressed her into a dull condition and she never was very clever.'

Now one of Dickens' abiding enthusiasms was the theatre. If he hadn't had a cold on the morning of his audition at Drury Lane Theatre, he would have become a professional actor and throughout his life he adored putting on plays and acting in them.

In 1856 he produced, directed, and starred in a melodrama called

The Frozen Deep

, written by his friend, Wilkie Collins. His two daughters played the female leads. But the following year when the production was re-staged in Manchester, he decided to use professional actresses instead.

He was introduced to and engaged two sisters â Maria Ternan, and her younger sister, Ellen.

Ellen was a young, slender, beautiful, little thing â Dickens fell madly in love with her. He was forty-five years old. She was⦠seventeen.

Music

.]

He bought Ellen a bracelet as a present. It was delivered by mistake to his wife, Catherine. One day their daughter, Kate, came into Mrs Dickens' bedroom and found her mother tying on her bonnet, with the tears pouring down her faceâ¦

âYour father insists that I call on Ellen Ternan.'

Kate said, âYou shall not go' â but she did.

You see, Dickens' most passionate enduring relationship was with his public, and he was terrified of losing their affection.

He was determined to devise an acceptable separation. He suggested to Catherine that she should go and live in their country house â Gadshill â while he remained in London, and she should only come to London when he went to the country. Catherine refused.

Then he suggested she should live in France while he remained in England. Catherine refused.

Finally â and most bizarre of all â he suggested that Catherine should live in the upstairs rooms of their house in Tavistock Street, and only come downstairs when they were entertaining visitors.

He got rid of Catherine, but he kept on her sister, Georgina (Mary's replacement), who'd come to live with them when she was fifteen and she never left. She stayed on in Dickens' house, looking after him and her sister's children till the day he died â in fact, he died in Georgina's arms, and she is the principal beneficiary in his will.

I don't think they were ever lovers, but he described her, just as he had described her sister, Mary, as âthe best and truest friend man ever had'. Dickens had a strange affinity with his sisters-in-law.

Further to retain that precious affection of his public⦠Dickens published a letter on the front page of his own

magazine

Household Words

, in

The Morning Post

, in

The Times

, and later in

The New York Tribune

, a letter to the public, in which he said that Catherine and he had âlived unhappily together for many years', that she had been a bad mother and had lost the affections of her children and that she was of unsound mind. Catherine never responded to these calumnies.

He wanted to publish the letter also in

Punch

, the foremost comic magazine of the day, but the editor, his great friend Mark Lemon, refused because he didn't think it was very funny. Dickens didn't speak to him again for twelve years.

Finally a separation settlement was drawn up. Dickens gave Catherine £600 a year, her own house, Number 70, Gloucester Crescent, her own carriage, and one of her nine children â the eldest son, Charlie â chose to live with his mother. At the time that they left, her youngest child, Edward â known as âPlorn' â was only six years old.

So the carriage bearing Catherine rolled away for her long stay in Gloucester Crescent. She lived there for twenty-two years. She never saw Dickens again. She only saw her two daughters when they would come for their music lessons to the house opposite.

Catherine would stand at the upstairs window, looking through the lace curtains, waiting for her daughters to turn and wave at her as they went inside. But they never did.

They were reconciled only after Charles Dickens' death and Kate was with her mother when Catherine was dying: Catherine handed her daughter a bundle of letters tied up in blue ribbon â they were Dickens' first letters to her. She said: âgive these to the British Museum, that the world may know he loved me once'.

Catherine is buried in Highgate Cemetery next to her baby daughter Dora. The letters are in the British Museum. Ellen Ternan married a clergyman and lived on 'til 1914. By an extraordinary coincidence she is buried in Southsea, in the same graveyard as Dickens' first love, Maria Beadnell â only Maria lies in an unmarked, pauper's grave.

At the time of the separation, Dickens was writing

Little Dorrit

.

âSo, the Bride had mounted into her hansom chariot⦠and after rolling for a few minutes smoothly over a fair pavement, had begun to jolt through a Slough of Despond, and through a long, long avenue of wrack and ruin.'

Other nuptial carriages are said to have gone the same road, before and since

Music under

â â

Autumn Leaves

'.]

Miss Havisham:

Great Expectations

, 1860â61

In an armchair, with an elbow resting on the table and her head leaning on that hand, sat the strangest lady I have ever seen, or shall ever see.

She was dressed in rich materials â satins, and lace, and silks â all of white. Her shoes were white. And she had a long white veil, and bridal flowers in her hair, but her hair was white.

She had not quite finished dressing, for she had but one shoe on; the other was on the table near her hand.

I saw that everything within my view which ought to be white, had been white long ago, and had lost its lustre, and was faded and yellow. I saw that the dress had been put upon the rounded figure of a young woman, and that the figure upon which it now hung loose had shrunk to skin and bone.

âWho is it?'

âPip, ma'am.'

âPip?'

âMr Pumblechook's boy, ma'am. Come to play.'

âCome nearer; let me look at you. Come close.'

When I stood before her avoiding her eyes I took note of the surrounding objects in detail. I saw that her watch had stopped at twenty minutes to nine, and that a clock in the room had stopped at twenty minutes to nine.

âLook at me. You are not afraid of a woman who has never seen the sun since you were born? Do you know what I touch here?'

âYes, ma'am.'

âWhat do I touch?'

âYour heart.'

âBroken! I am tired, I want diversion, and I have done with men and women. I sometimes have sick fancies and I have a sick fancy that I want to see some play. There, there! play, play, play! You can do that. Call Estella. At the door.'

To stand in the dark in a mysterious passage of an unknown house, bawling Estella to a young lady neither visible nor

responsive

, and feeling it a dreadful liberty so as to roar out her name, was almost as bad as playing to order.

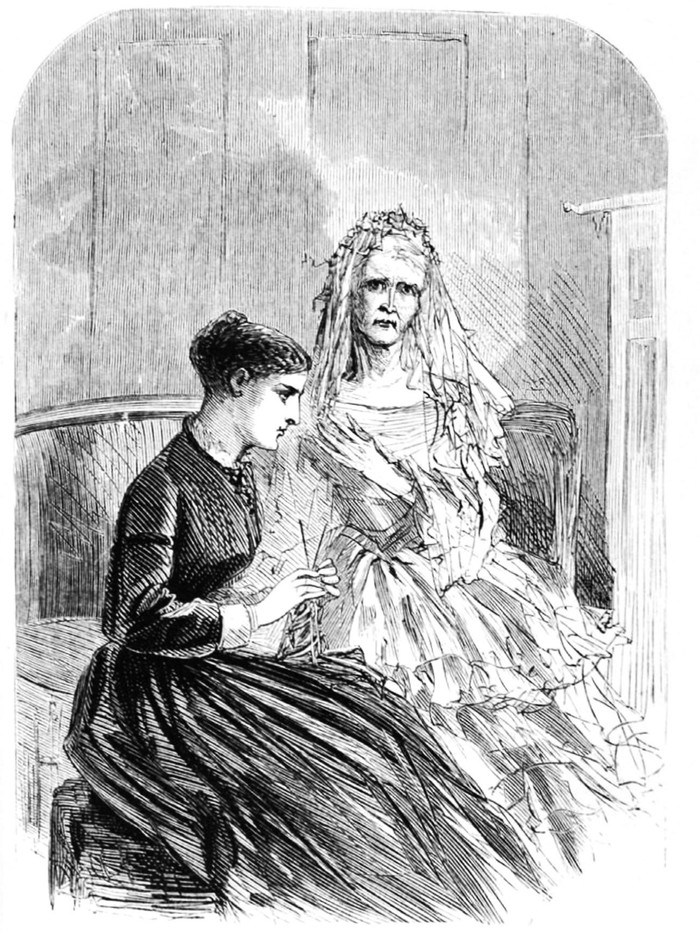

Miss Havisham and Estella â Sol Eytinge

Estella answered at last, and her light came along the dark passage like a star.

Miss Havisham beckoned her to come close, and took up a jewel from the table, and tried its effect upon her fair young bosom and against her pretty brown hair.

âLet me see you play cards with this boy.'

âWith this boy! Why, he is a common labouring-boy!'

âWell? You can break his heart.'

âWhat do you play, boy?'

âNothing but Beggar my Neighbour, miss.'

âBeggar him,' said Miss Havisham to Estella. So we sat down to cards. I played the game to an end with Estella, and she beggared me.