Discourse and Defiance Under Nazi Occupation: Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1940-1945 (2 page)

Read Discourse and Defiance Under Nazi Occupation: Guernsey, Channel Islands, 1940-1945 Online

Authors: Cheryl R. Jorgensen-Earp

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Historical, #Europe, #Germany, #Great Britain, #Leaders & Notable People, #Military, #World War II, #History, #Reference, #Words; Language & Grammar, #Rhetoric, #England

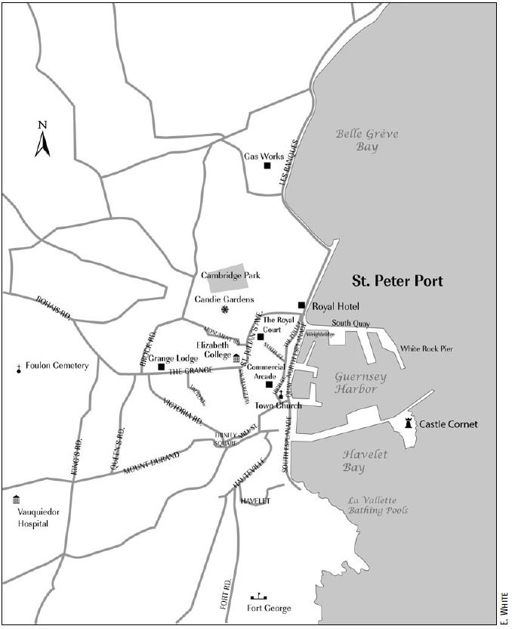

In her diary, Winnie described how the German planes bombed the harbor, machine-gunning people: “The first bombs fell plumb in the middle of the long line of tomato lorries waiting for the boat, creating havoc. They circled round and came back again and again.” People on the pier tried to take shelter underneath the lower landing, but they were not the only ones being gunned down. An ambulance on the other side of St. James' Church, ferrying the wounded to the hospital, was machine-gunned, killing Joseph Way, the driver.

6

During a lull, the old couple with the kitten and Winnie's friends Colonel and Mrs. Carey, who had joined them on the ground under the trees, made off for their homes. Winnie lay there alone, looking over the newspaper in a strange state of calm. She finally rose and ran most of the way to the First Aid post where she was a volunteer, “looking for cover in every street.”

7

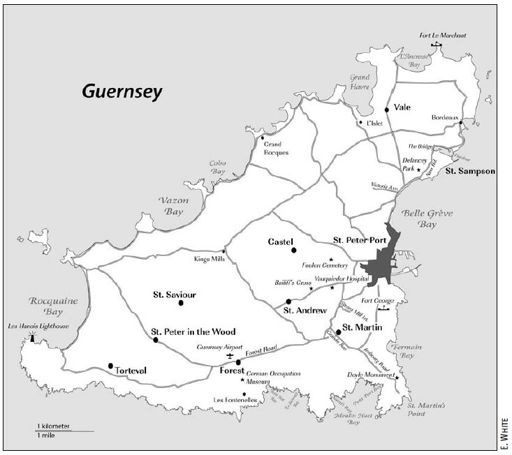

The saddest, most personal account of this unprovoked attack on civilians came from the diary of Arthur J. Mauger, a grower from Kings Mills, Castel. In ledger books scripted in his beautiful flowing hand, he had long recorded an account of daily life. On June 28, he started with his usual report of the weather; the day was “Fine.” He described how he “messed about the place” doing odd jobs with the men. In the afternoon, all the men, including his step-grandson Frank, left to go to the White Rock (referring to the pier off of the South Quay of the harbor) to see to the arrival of cattle abandoned by those evacuating the Island of Alderney. Thus, the men were in precisely the wrong place, standing on the pier when the air raid occurred.

Arthur recorded in his entry for the 28th: “Frank was one of the seriously wounded. Frank Le Page and his two sons are missing and probably killed, also P. Le Noury, all neighbours…Frank was chatting to his workman and others, but was the only one in that lot to be hit.” His next entry on Saturday, the 29th, confirmed his worst fears: “A very sad day for nearly all of us neighbours. Good old Frank my step grandson died last night about 3 a.m. through the terrible wounds he had in the last evening ‘airraid’ he was 32 and 2 months 18 days. Frank Le Page [from] Millmount and his two sons were killed outright last evening. Also P. Le Noury, in fact there was 25 killed and 33 injured, the wives are in an awful state…Frank Le Page was 49, the sons 19 and 14 respectively.”

8

The final count would actually be thirty-four dead and dozens more wounded, the surreal horror of an attack on innocent farmers loading their crops captured in the memoirs of Guernsey journalist Frank Falla: “The blood of the wounded and the dying mingled with the juice of the tomatoes.”

9

This, what builder and grower Jack Sauvary called in his own diary “the eventful outrage,”

10

was the first contact the people of Guernsey were to have with the Germans who would occupy them for the next five years. Military occupation during and following wars is a recurrent situation, and one whose rhetorical aspects have yet to be fully explored. In recent decades, our understanding of resistance under occupation has expanded greatly, developed in part through studies by Roderick Kedward and others of the German occupation of France.

11

Slowly, there has developed a new appreciation of formerly “unrecognized resistance,”

12

and this has helped redefine resistance as a whole. We could take as a broad definition of resistance the one offered by Christopher Lloyd: “the struggle for personal and political liberty against an oppressive, external force.”

13

Yet, we know that the struggle against domination is often internally as well as externally directed, particularly when we look at oppressive power inequities outside of a military situation. Resistance strategies develop in the struggle of workers against domination within an oppressive corporation, or as a response to slavery or economic servitude within an oppressive society. Even under military occupation, particularly in instances of widespread or official collaboration, resistance becomes internal as well as external. Kedward makes the point that, in the case of Vichy, “what started as a national defeat by an

external

enemy had quickly become a civil conflict between

internal

enemies.”

14

If we can expand Lloyd's definition of resistance to encompass opposition to internal as well as external oppression, then his use of the term “struggle” opens the concept of resistance to a myriad number of covert as well as overt acts. In the case of military occupation, the very fact that an occupied people are held under force of arms provides an expectation that the counters to that power will be overt and hold the potential for violent overthrow. This view is not unreasonable in many situations of military occupation, and there are multiple studies of resistance activities, both organized and unorganized, that have met military power with sabotage and counterforce. However, the fact that such resistance does exist in certain cases has led to the mistaken notion that resistance is synonymous with violence, or at the least with quantifiable overt actions. Even in situations that lend themselves to violent opposition, discrete acts of resistance tend to be isolated eruptions, whose very visibility shelters the size and complexity of a submerged supporting structure of psychological defiance.

15

And that underlying foundation of community mindset is constantly shaped and structured by the ebb and flow of events, information, and opportunities.

Modern Americans and Britons have learned from our own experience in Iraq what others have learned before us. Violence or sabotage may be the apparent problems for occupying forces, but these acts are facilitated by psychological resistance. “Hearts and minds” truly are at its root, and dramatic or violent actions are simply the most visible forms of an opposition to power. “Resistance,” Andrea Muhi Brighenti claims, “may be helped by invisibility, which furnishes a place to hide from domination.” Thus, Brighenti finds in resistance a need to seek “the realms of the informal, the implicit and even the trivial.” Particularly in military contexts, the resister is unlikely to prevail in a struggle head to head on the battlefield of the powerful, and thus must seek new, and often hidden, locations where resistance may flourish. While invisibility may prevent detection, it also hinders acknowledgment that resistance has even taken place.

16

Therefore, some forms of resistance, often those that are psychological and expressed symbolically, have largely gone unrecognized. As Hazel Knowles Smith states, “Even harder to quantify and evaluate is the case for resistance of opinion,”

17

but this is the very case that I intend to make in this study.

Capturing the nature of occupation resistance has been difficult for scholars, and this problem has resulted in some slippery terminology. The desire has been to find a descriptor that would separate the bulk of Island resistance from the type of organized resistance movement that developed on the Continent and that tends to constitute resistance in most people's minds. Specific acts during the Guernsey Occupation have been referred to as “passive patriotism,”

18

“silent resistance,”

19

“spiritual resistance,”

20

and even (when describing the actions of Salvation Army resister Marie Ozanne) “Christian resistance.”

21

All of these terms are perfectly accurate in the specific instances to which they were applied, but none can fully capture the vast sweep of resistance, some of which was passive and personal and some active and organized, some silent and some anything but silent. Perhaps the best way to encompass all of the resistant activities in Guernsey is to consider them forms of rhetorical resistance, for all in some way involve the manipulation of discursive or nondiscursive symbols, and all are designed (however subtly) to “induce to attitude or action,”

22

which is the purview of rhetoric.

The concept that there is a resistance that relies on symbolic forms arising from the common people

23

and serving as “rhetorical antidotes”

24

to power is not entirely new, and its treatment has already served as the basis for many new understandings of subjugated people. Our view of the resistance wielded by African-Americans during slavery and under Jim Crow has been widely expanded by an attention to the subtle discursive and nondiscursive means of

opposing power. The past few decades have provided detailed studies of these tactics, where spirituals, work slowdowns, folk tales, and feigned illness or ignorance were some of the many subtle methods of countering oppression.

25

The same re-visioning has taken place in women's history, as what was previously taken to be female passivity and acceptance of a subjugated position in society has been transformed by close attention to private and public rhetorical means of challenging male domination.

26

Despite these successes and the many calls to approach “vernacular discourse” as a worthy object of critical study and thus to expand our understanding of resistance,

27

we are often slow to acknowledge the extent of the impact of rhetorical resistance.

Scholars have been particularly hesitant to make claims for the power of rhetorical resistance as a counter to the force of arms, leaving it primarily as a preparatory stage for movements of “real” resistance or actual revolution. I believe that this tendency has to do with the realities of the specific opposition movements examined thus far, where symbolic means of resistance often emerged early on and then were overshadowed by more overt acts of subversion. For example, the concept of symbolic means of resistance as a forerunner of an organized movement may be seen in Nathaniel Hong's study of the German occupation of Denmark, and his detailing of some of the methods used from 1940 to 1942 (graffiti, leaflets, posters, songs, chain letters, movie demonstrations) until the emergence of “an active resistance movement.” Hong's description of these tactics is fascinating, and he posits that “The simplicity, even crudeness, of these strategies made them well suited to the first stage of resistance.”

28

More recently, Kerry Kathleen Riley's excellent study of the grassroots social movement in the German Democratic Republic prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall situates this form of symbolic opposition as one part of “a story of rhetorical resistance, reclamation, rebellion, and revolution.” In the case of the GDR, what began as private resistant exchanges, often in the form of jokes, would evolve into the “quasi-public sphere” of group work and prayer services in the Evangelical Lutheran Church, and then blossom into the slogans, banners, and marches of the “demonstration culture,” finally to be fulfilled in the revolution, the “winning of the street.”

29

In these studies that highlight a symbolic resistance as the forerunner or companion of a more overt resistance movement, we are able to appreciate the value of subtle oppositional tactics, or “everyday subversions,” in Riley's phrase. But what can we make of its efficacy when rhetorical resistance is not an appetizer or side dish but the main course, when it is practically the sole means of opposition to domination under force of arms? In this study, I would like to approach rhetorical resistance under conditions of military occupation as a complete and very real form of resistance in itself, with its own identifiable structure and its own value as a long-term method of opposition to power. In doing so, I begin with a series of questions about the shape of a more subtle form of resistance, one rooted in discursive and nondiscursive symbols.