Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir (18 page)

Read Does the Noise in My Head Bother You?: A Rock 'N' Roll Memoir Online

Authors: Steven Tyler

Tags: #Aerosmith (Musical Group), #Rock Musicians - United States, #Social Science, #Rock Groups, #Tyler; Steven, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Social Classes, #United States, #Singers, #Personal Memoirs, #Rock Musicians, #Music, #Rich & Famous, #Rock, #Biography & Autobiography, #Genres & Styles, #Composers & Musicians, #Rock Groups - United States, #Biography

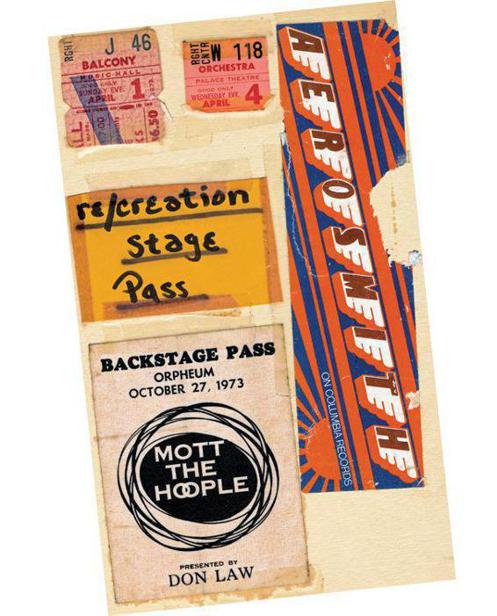

We spent the whole of the 1970s on tour. It was just one long endless road trip. We’d stay out on the road for a year and a half. The only time we’d come off the road was to record an album. We went out with everybody: Mott the Hoople, the Mahavishnu Orchestra, the Kinks. We toured the Midwest that debut LP summer in a couple of limos with the two guys from Buffalo and Kelly, our new road manager: Robert “Kelly” Kelleher. Our first real tour was opening for the Mahavishnu Orchestra. John McLaughlin, in his white robes, burning incense. Spreading

his

transcendental six-string scent . . . sweet. We opened for the Kinks in the Northeast and Midwest; Ray Davies called us Harry Smith, after the hair on Kelly’s back. We were opening for bands that were our heroes—Ian Hunter from Mott sang like no one else did. Groups that were beginning to fade a bit . . . and whose audiences we wanted.

W

e stickered every tollbooth from Boston to NYC to L.A. with our first Aerosmith sticker, 1973.

We used to do out-of-town shows with Mott the Hoople. We’d make up to five hundred bucks a night, with them. To save on getting there, we’d use these bogus DUSA—Discover USA—tickets that were, like, 50 percent off. You were supposed to be a non-American passport-holding tourist to get them, but we found this travel agent who helped us out. Then I’d go up to the counter with an English accent: “Hallo! We’d like to preboard,” or whatever the fuck it was. That’s how we were able to do that.

T

om, 1974 . . . so I could hold him hostage. Not anymore . . . (Steven Tallarico)

Then we’d come home and play every high school in the area and little neighborhood colleges. We’d throw a thousand dollars at the athletic fund, and we’d do everything else. And they’d give us the four walls—meaning we’d make all the money. It soon became a little status thing: “Oh, Aerosmith played at our high school!” And then Wrentham High and then the Xavarian Brothers out in Westwood and everybody wanted to have Aerosmith play at their school and we pretty much did.

We did it at our high school, too, and at BC, Boston College. At the Q Forum at BC, that was when I knew the band had made it, the crowd was so huge and out of control. (Meanwhile, our Father Frank is in the hockey team dressing room with Father So-and-So, getting him drunk. Oh, those were the days!) Because there were so many people that we were almost afraid to go on, we went into the bathroom with a security guard, Johnny O’Toole, outside the door. The kids were throwing chairs through the bathroom window and climbing in the window! Ripping the back doors off the arena, just blowing the windows out of the place, trying to get into this hockey rink, which they did. So we ran out of there and went down a hallway. Boston College, 1973. There were so many people, a real freak show.

Sometime in ’73 this guy Tony Forgione said, “I’m going to open a club”—it was the old Frank and Ike Supermarket where Eric Clapton and Joey Kramer had played years ago—and asked us to headline. Al Jakes was around, and all those goofy guys from Frank Connally’s old crew in Framingham. We had Billy Squire and the Sidewinders open for us. The fire department was there and they’d posted a certain capacity. “Here’s how we’re going to do it,” I said. “We’re going to fuck ’em up tonight.” When you’ve got that many people coming in, you estimate the crowd by the median between three clickers. We had three different clickers between us. But the count is always jive because someone somewhere is always on the take! When we were doing it, we’d count every third person coming in. We stuffed that club. We opened one night and the fire department closed us down the next night. The club never opened again. And we took all the money! Steamroll.

Elyssa Jerret, who married Joe Perry, remained unbelievably gorgeous. Everyone was in love with her. She’d been Chicago guitarist Joe Jammer’s girlfriend, had gone to England, worked as a high-fashion model, had dinner at Jimmy Page’s house at Pangbourne on Thames . . . and all that. She felt this patina of über-hipness had rubbed off on her.

On the road, we played “Dream On” every night. I thought that was the song that defined me. But not everyone shared my passion for that ballad. Every time we started to play “Dream On,” Elyssa would roll her eyes and go, “Oh, fuck! Not

this

song again! God! Let’s go snort some blow!” She’d make sure I saw her. And all the guys in the crew followed her into the bathroom. While she was cutting up lines, it cut me to the core—it broke my heart. It was the song that hurled us to wherever we are today and beyond. Born somewhere between the red parachute and my dad’s piano, that song took this band to places where we could only dream on.

Back in the early days before we’d had a hit on the radio, we made our reputation playing live and loud. As an opening act we’d only get to play three or four songs, so if we wanted to strut our stuff, slow songs weren’t what we’d play. You do the hard and heavy down and dirty to get your ya-yas out. Joe didn’t like “Dream On” from the start, didn’t like the way he played. He felt we were a hard rock band, and here we were staking our reputation on a slow ballad. And to Joe, rock ’n’ roll was all about energy and flash. When it was first released in 1973, “Dream On” only made it to 59 in the Hot 100 charts. But, you know, the song got bigger and bigger and I got my “

taa-daa!

” moment. When it got rereleased in 1975, it went to number 6 in the charts. I got a Grammy for it, but I would gladly have traded any gold album just to have my brother love that song. Wait a minute, I take that back!

The concerts were getting more rowdy and outrageous. We opened on August 10, 1973, for Sha Na Na at Suffolk Downs racetrack near Boston. Thirty-five thousand kids showed up and got so rowdy they had to stop the show. Awright! Now that was more like it.

Aerosmith had been big in Detroit from the beginning. We had a loud, flashy, gritty, metallic vibe.

Rolling Stone

called us greasers, “Wrench Rock,” which was strange because we looked more like medieval troubadours. We were hardly grease monkeys—mechanics of ecstasy, maybe. But they did love us in the rust belt towns: Toledo, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit. The only part of us that was heavy metal was the clang of steel . . . the body shop, assembly-line, car-based clamor. We’re a people’s band. Judy Carne—the English comic who starred in the iconic TV show

Laugh-In

and dated Joe for a stint in the early seventies—thought we were the voice of the mills and the malls. And those working-class towns were the places that embraced us early on.

We had to get out there, however we could, to the fans. We knew that the energy we had was contagious, that we would infect the whole colony. Evidence that we were getting through came when we started pulling Mott the Hoople’s audience. Kids started jumping over the barriers, climbing onstage, and grabbing at us. Detroit was the turning point for us. We played Cobo Hall three times in ’75. After that, we exploded. There’s a ton of bands out there competing for the hearts, minds, and bucks of the sacred rock fan, but Aerosmith has managed, for better or worse, to get to the ear (and various other organs) of a lot of them.

Still, our core audience was always the Blue Army—the hard-core kids from the Midwest. They were the Blue Army because they all wore denim jeans; the place was a sea of blue. Just like when you go see Jimmy Buffett and his Parrothead contingent . . . look out, it’s Q-Tip Nation. Everyone’s fucking gray and they love it. And we all got to ride that Aerosmith train to the outer reaches.

Our interest was the same as the kids’: rocking out, getting them off . . . getting

us

off! Like I always inquire, “Was it as good for you as it was for me?” Inspires a quick verse . . .

Was it as good for you as it was for me?

That smile upon your face makes it plain to see

What I got, uhuh, what you got, oo-wee

So was it as good for you as it was for me?

Confessions of a

Rhyme-a-Holic

W

hen I was in my late teens, seventeen or eighteen, I used to come home from one-night stands with local New Hampshire bands like Click Horning and Twitty and Smitty and crash at Trow-Rico, fucked-up on trashy skunk New England weed. I began to write a song on an old Este pump organ about alienation. The ancient Victorian instrument, made in vermont in 1863, lived in the studio where my dad practiced piano four hours a day.

In order to play on the pump organ, I’d have to sneak time during the day while the guests were swimming at Dewey Beach. The song started with a melody in my right hand that rocked back and forth hypnotically, out of the ether. That was “Dream On.”

I began it in F-minor with a C, C-sharp dischord. That gave it a haunting, Edgar Allen Poe kind of feel. I wrote much of the body of the song in Sunapee, where I knew I had something. The verses were composed at the Logan Hilton when we were working on our first album.

I’ve always said it’s about hunger, desire, ambition—a song to give to myself. Something about it was nostalgic and familiar, as if it’d been written by someone else years before (but if no one has, then you know you’re into something), or perhaps like I had written it years later and was looking back on all the things that have happened to me over the last four decades. “Pink,” off

Nine Lives,

felt that way, like it was somebody else’s. However interpreted, my primordial thought was that maybe I wasn’t put here on earth just to mow lawns.

Every time that I look in the mirror

All these lines in my face getting’ clearer

The past is gone. . .

Stream of consciousness mixed with the Grimm’s fairy tales my mother read to me from the crib till I had to read them to myself.

Sing with me, sing for the years

Sing for the laughter and sing for the tears

Sing with me, if it’s just for today

Maybe tomorrow the good Lord will take you away

The lyics to “Dream On” came in a thought . . . and my train of thought stops at every station.

By pure crazy chance last summer I found the very organ on which I’d written “Dream On,” in a house on the lake road near where I live. That road has become for me a kind of metaphor for my life. Beginning in the woods near my house, I remember the days I’d be up in Sunapee at the start of winter, really scared in the dark and not knowing what to do with my life. Then farther on, the road winds down to the harbor where Joe and I used to hang.

The road forms a loop, a three-mile jog that meanders past houses quaint and grand, beside grassy green fields, up and down grades. I would make the trek every morning for two months to prime myself for any upcoming tour. Nobody would ever guess that I get the breath to sing “Don’t Want to Miss a Thing” in fucking Russia from running this friggin’ loop. If I could make it up Heartbreak Hill down into the harbor and back up to the house still in one heart-pumping, breathless piece, I’d be ready for the campaign. Sometimes I’d run right off the end of the dock into the water, anointed by the waters of Mother Nature, baptized by freezing Lake Sunapee.

In live performance, before I go and sing that high note in “Dream On,” I do a little hyperventilating. I look down (like this—use your imagination) and I breathe in and out, in and out, rapidly . . . then I go,

“yeaahhh,”

and I hold my breath where anyone else if they were underwater would be going, “I gotta come up for air!” I learned how to go past that in part by making those treks around the lake . . . for the sake of holding the note.

Over the last ten years, as the condition of my feet has deteriorated from stomping stages since the seventies, the loop has become more and more challenging, but more on the wounded rock warrior later.

One night, during a nonaerobic stroll on the loop, I passed a house that was glistening with a flickering flame inside. The house was called “Witch Way.” Outside there were gargoyles and mannequins and twisty limbs from trees. I’d seen this house many times before, and every time I went past it I’d go, “I’d love to meet the person who lives there.” I’d stop out front and yell, “Hello, I love you in there!”

This time I shouted a little louder, and a sweet middle-aged couple, Sherry and Philip, invited me in. Philip’s a contractor; Sherry is a sculptor. Amazing bizarre stuff she’s made is all over the house. “Oh, my god,” I say, “can I look around?” A sculpture made out of a cello, another one—I can barely describe it—made out of gourds. And dried sunflowers. It looked like

The Wizard of Oz.

Meanwhile, on a huge flat-screen TV,

America’s Got Talent

is on the tube. Twenty girls that any guy would love to do.

In the front room, there’s an old organ, just like the one on which I’d written “Dream On.” I began playing and I felt like I was levitating. The organ felt very familiar. I was transported back to Trow-Rico all those years ago when I grabbed a few chords out of the air. Turns out, it was an Este pump organ made in Vermont in 1863—the exact type we had up at Trow-Rico.

“Where did you get this?” I asked.

“There was an old antiques store down at the harbor right across from the community store and the organ was sitting out on the porch,” she explained.

So they’d bought it in the eighties, which would have been about the time my dad sold Trow-Rico. Talk about serendipity! I’m called by my muse into a house that I’d never been inside, and there’s my old friend, the “Dream On” pump organ. Was it possible? I sat down, laid my hands upon the keys, and pulled out all the F-stops as I did thirty-five years ago. As I started pumping the organ, I could feel her start to breathe. We made musical love right then and there.

Sherry said she bought the organ at an auction in Sunapee the fall after my parents sold Trow-Rico and that it’s most likely the same organ. “I think the organ has a poltergeist in it that’s somehow attached to the crystal vase,” she told us. “I’d always kept this little crystal vase on top of the organ, but after we moved I decided to put it on the bookshelf. One night I was sitting on the floor drawing when this vase came off the shelf and hit me in the back, you know, but since I put it back on the organ, it hasn’t done it in nine years.”

I made Sherry promise me that if she ever sells that organ, she’ll let me make the first offer. It’s the shit. It really truly is a pump organ with all the stops. A strange thing about antiques— they had another life before we get introduced to them. It’s like an ancient string of beads that you might find in Mesopotamia. You don’t know who they could have belonged to. They tell you only “These are beads from the ancient lands, found in the ruins.” Or they were found in a barnacle-encrusted chest off the coast of the Holy Land. Did they once hang around Mary Magdalene’s neck?

W

hen a song comes to you and you write it in ten minutes, you think,

There it is. Dropped in our laps like a stork dropping a baby. It was always there. The song. On the inside. . .

I just had to get rid of the placental crap that was around it. Because at the end of the day, who really wrote that? If Dylan were here, he would tell you in his laid-back Bobness, “Well, now where would it come from?” Out of the blue, lines come to

you . . .

You think you’re in love like it’s a real sure thing

But every time you fall, you get your ass in a sling

You say you’re in love, but now it’s “Oooh, baby, please,”

‘Cause fallin’ in love is so hard on the knees

You see it floating there and say, “This should be caught.” It’s like those Native American dream catchers. I look at those and go, “Oh, my god, that’s my fuckin’ brain!” I would see something or hear Joe playing, I’d yell, “

Whoa, whoa!

What was

that

?” Or a passage in a Beach Boys song where they go to the bridge and I’ll hear an entire song in there.

W

hen I was a kid, my mom would read me all these stories and poems, Dickens and Tennyson and Emily Dickinson. That’s where I got my rhyming from. I’m a rhyme-a-holic. It made me curious in life to wonder why, when you look out the back window of your car and you stop for a red light, the world seems to be coming back at you. Everything you pass catches up to you; poems from the past can turn into songs in the present through curiosity and imagination.

But it catches up to you, like when I had dreams about flying or floating up to the ceiling and then out the window and over a city. I’d have a piece of wood, be on a hill, slap it to my chest, and I’d catch winds like a sled does snow and start lifting up and I’d fall and roll down the hill and I’d grab it again and catch the winds and be afraid I’d fall down again and get back up and those winds would blow me out to sea. I’d go so high and find myself in a tree. And I’d wake up going, “Are there cars that levitate?” I’d feel that sensation in my chest like when you fall. The stories inspired the dreams, so thank you, Mom, for the stories.

I was twizzling the little skull I have twined in my braid and went,

hmmm, hmmm.

I started off with something that everyone’s familiar with, like a line from “Dream On.”

Every time I look in the mirror

All these lines on my face getting clearer

Sing with me, sing for the ye-ears.

I’ll grab a little of that and throw it in like yeast. It’s 2010, and if I was to connect the dots from “Dream On” till now, I would say:

All the lines on my face as I sang for the years

was the skull in my braid barely down to my ears?

I could deal with the screamin, you know how that goes

when the skull in my braid hung down to my nose.

And you get the rhythm going and in no time at all it’s writing itself.

I’ll have had me a pint and be hanging with Keith

when the skull in my braid’s grown down to my teeth.

If I’m not on tour, well, you’ll know where I’ve been

when the skull in my braid’s grown down to my chin.

When the agents and labels get round to a check,

that old skull on my braid will be down to my neck.

And I’ll take that old check and I’ll rip it to bits

by the time my old skull has grown down to my tits.

With my girl in the sun and I’ll maybe get faced

when the skull in my braid’s grown down to my waist.

I’ll be rippin it up with a mouth full of sass

when the skull in my braid’s lookin down at my ass.

And life’ll be good and life will be sweet

if that skull in my braid makes it down to my feet.

It’s been second to none, that no life can compare,

when that skull in my braid gets cut out of my hair.

Yesterday and today I was thinking about the timelines between the verse and the curse (chorus) and how it all works together. There are four elements to writing a song, or as they say in comic book land . . . the

Fantastic Four.

If you break it down, there’s melody, words, chords, and rhythm—put those down in any order and you’ve got something you can play to piss your parents off.

When I was married, I used to think of myself in the third person. I would say to my wife, “Well, I can’t believe you’re married to this guy in a band,” you know. “How could you

do

that?” Then a couple of years ago my daughter Liv called me up and said she was marrying Royston, another guy in a band. There it was again, like a shadow, you know.