Dog Sense (46 page)

Authors: John Bradshaw

Basenjis aside, many of the behavioral traits that were measured varied almost as much within breeds as between them. The differences between individual dogs were found to be based upon seven different emotional traits (impulsivity, reactivity, emotionality, independence, timidity, calmness, and apprehension) and only two ability traits (general intelligence and the ability to cooperate with people). Whether the

dogs performed well or badly in most of the tests depended not on differences in their “intelligence” but, rather, on their emotional reactions to the situations they were put in and their ability to glean clues from the experimenters about what they were supposed to do. Thus while working traits may be characteristic of breeds or types, emotional traits show much overlap between breeds.

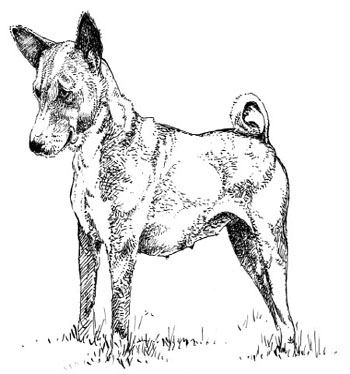

Basenji

Moreover, this studyâintentionallyâdid not take into account a very important factor influencing a dog's character: the individual's experiences during the first few months of life. All of the puppies were raised under standard conditions, in order to minimize the effects of such experiences. In the real world in which prospective owners look for pets, such early experience can overwhelm most genetic factors. A cocker puppy born and raised in an isolated outhouse will behave much like a beagle raised under similar conditionsâtimid and frightened of anything out of the ordinaryâand will be equally prone to developing fearful avoidance or aggression problems later in life.

Some breed organizations place insufficient emphasis on the role of environment in shaping a dog's behavior. This is hardly surprising, as they are loath to admit that any of their breeders rears puppies under less than ideal conditions. A dog's character is the product of a complex interplay between genetics and the dog's experiences growing up.

No breed standard for character can protect against the damage done to a puppy by keeping it in an impoverished environment for the first eight weeks of its life.

Perhaps the most important personality trait a potential dog owner will want to know about is whether or not a particular breed is inclined toward aggression. But are there meaningful distinctions between the breeds in this regard? The relative contributions of the genetics and environment in determining whether a dog is likely to bite are still hotly debated: One of the most contentious aspects of personality and breed-specific behavior is whether aggressiveness is a genetic trait among dogs. It's universally accepted that aggressiveness can be affected by experience, but opinions differ where other contingencies are concerned. Many experts now agree that much aggression in dogs overall is motivated by fear, not by anger, and that early experience and learning play a huge role in determining whether an individual dog turns its aggressive feelings into an actual attack. At the same time, however, genetic influences are hard to rule out. In the case of breeds designed for fighting and guarding, they must play a role, although not necessarily a deterministic one.

Since differences in experience were minimized in the Bar Harbor project, the scientists' data should be a good place to look for genetic effects on aggressiveness. All of the dogs in the study were tested for aggressive tendencies under a variety of scenarios, but such tendencies did not emerge in the analysis as one of the seven underlying emotional dimensions. Rather, aggressiveness was strongly linked to general reactivityâcharacterized by a generally fast heart rate, rapid progress around obstacle courses, and so on. However, none of the five breeds selected for the Bar Harbor project, with the possible exception of the basenji, was especially noted for its aggressiveness, so this study cannot rule out the possibility that genetics may influence aggressiveness in some other breeds, especially those bred for fighting and guarding.

Aggression in such dogs is still an issue of real public concern, despite many measures taken to reduce the risks involved. Except in very carefully defined and tightly regulated circumstances, such as the training of police dogs in public order enforcement, aggressive dogs are unacceptable to most of society. In recent years, attempts to remedy the problems

caused by canine aggression have largely taken the form of breed-specific laws, many of which have proved difficult to enforce. These laws vary considerably in detail from country to country, but most ban or place severe restrictions on ownership of pit bull terriers and similar breeds. But are pit bulls really different from other dogs, or do they simply have the right “look” for those who wish to use dogs as weapons? The truth probably lies somewhere in between.

Fighting dog

Reports of biting incidents are notoriously unreliable,

15

so care must be taken in considering whether a dog that has attacked someone was actually a pit bull. Since pit bull types generally lack authenticated pedigrees, pit bulls cannot be called a “breed” in the same sense that, say, cocker spaniels are. It is thus difficult to identify pit bulls as such; other breeds, most notably the Staffordshire terriers, are often mistakenly referred to as “pit bulls.” Two other confounding factors may also contribute to the pit bull's reputation: (1) contagious overreporting of bite incidents following one well-publicized occurrence and (2) the deliberate choice of this type of dog by irresponsible owners.

Legislating against a whole breed can be justified only if there are underlying biological reasons why that breed should be aggressive. If, on the other hand, the main cause is irresponsible ownership, manifested as

a desire to use the dog for fighting (or to merely give the impression of doing so), then outlawing one breed is unlikely to solve anything. Either the breed will be pushed underground, further into irresponsible ownership, or other breeds will take its place.

Pit bulls are certainly descended from dogs intended for fighting. The ancestry of today's pit bulls can be traced back to bulldogs. Bulldogs were used for bull-baiting in the UK until the sport was made illegal in 1835; after that, they were used for dog-fighting on both sides of the Atlantic. Such dogs have been selected over many generations for specific characteristics: a low level of fight inhibition; rapid escalation of any conflict, often omitting the usual threat communication; and absence of the bite inhibition seen in many guarding breeds, such as German shepherds, who grab and hold but usually do not shake and tear like pit bulls. (The “locking jaw” of the pit bull is, however, a myth.) Breeders reputedly try to select against aggression toward people, for the safety of the owners and their families at least. But it's not clear that such selection is effective: Since dogs in general are far more likely to choose their targets of aggression on the basis of experience than through genetically driven preference, they are apt to act out against anyone they perceive as threateningâincluding their owner.

Although some pit bulls are unarguably dangerous, many are not. Granted, in 1986, pit bulls were responsible for seven out of eleven fatal dog attacks in the United States, making this breed at least thirty times more likely to have bitten than any other breed. However, none of these seven were breed-club-registered animals, so it was impossible to quantify the effect of their ancestry on their aggression. Furthermore, it is likely that the way their owners had treated them, and especially the way they had trained them, had made the major contribution to their extreme aggression. Despite their fearsome reputation, the vast majority of the 1â2 million pit bulls in the United States at that time had probably never bitten anyone.

The connection between breed/personality and actual biting incidents is imprecise at best, even if one accepts that some breeds are genetically predisposed to be more likely to be aggressive than others or that there is such a thing as an aggressive personality trait in dogs. Even within so-called aggressive breeds, the dogs who actually attack are extreme outliers.

Moreover, the reasons for their extreme behavior are rarely investigated thoroughlyâmost of these dogs are simply destroyed.

In short, there is no direct evidence that breed differences in aggression have much to do with genetics. On the one hand, a very high percentage of individual dogs in any breed, including those held to be the most “dangerous,” are not involved in attacks (see

Table 10.1

); on the other hand, the circumstances under which dogs express aggression are highly modifiable by each individual dog's experiences, including but not limited to training. Indeed, none of the statistics on dog attacks distinguish between the “genetic” hypothesis on which the legislation is based, and the possibility that some breeds are much more likely to be kept by irresponsible owners.

By contrast, genetic factors are much more evident in the inherent aggressiveness of wolf hybrids, or “wolfdogs.” Potentially more dangerous to their owners and the public than pit bulls and other fighting dogs, these hybrids between wolves and dogs have achieved cult status over the past quarter-centuryâespecially in the United States, where there may be as many as half a million of them. Wolves and dogs are adapted to such different environments that such extreme outbreeding was certain to produce animals that fit neither the wild niche nor the domestic oneâand, indeed, wolfdogs are renowned for the unpredictability of their behavior.

TABLE 10.1 Numbers of Dogs Involved in Attacks on People and Dogs in New South Wales, Australia, in 2004â2005

16

| Breed | Number (as registered) | Percent of breed |

| German shepherd | 63 | 0.2 |

| Rottweiler | 58 | 0.2 |

| Australian cattle dog (“Kelpie”) | 59 | 0.2 |

| Staffordshire bull terrier | 41 | 0.1 |

| American pit bull terrier | 33 | 1.0 |

| Others | 619 | Â |

Wolfdogs have been held responsible for a disproportionate number of attacks on humans; for example, in the United States between 1989 and 1994 they were believed to be accountable for more human fatalities (twelve) than pit bulls (ten). There appear to be two distinct motivations behind such attacks. Some seem to stem from challenges over resources, as when a person tries to remove a wolfdog's food. Other attacks seem to stem from the wolfdogs' perception of humans (especially children) as potential prey items, at which point they appear to express their full range of predatory behavior right through to the kill. Accordingly, the Humane Society of the United States, the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, the Ottawa Humane Society, the Dogs Trust, and the Wolf Specialist Group of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Species Survival Commission all consider wolfdogs to be wild animals and therefore unsuitable as pets. Although the way that a wolfdog is kept will undoubtedly affect whether it is dangerous or not, the wolf-type genes that it carries are undoubtedly the major influence on its behavior.

But apart from these hybrids, the lack of any firm genetic basis for much “dangerous dogs” legislation makes it unfair to dogs. On top of this, the slow-grinding machinery of the legal system can mean that enforcement of such legislation will make a bad situation considerably worse for dogs “arrested” for biting. Most of these dogs are housed in kennels for months or even years while they wait for the courts to decide their fate, making retraining and rehabilitation all the more difficult or even impossible.

Aggressive dogs are clearly an issue of public importance, yet paradoxically they may not be the greatest threat to dog welfare that has been posed by selective breeding. Whenever dogs are selected for special aspects of behavior, there is a risk, as yet only dimly perceived, that they might suffer. This is because the choices that animals frequently have to make between one response to a situation and another are often driven by emotion. Natural selection keeps these connections functional. A wolf that is hyper-anxious or fearful or angryâor in puppyhood was overattached to its motherâwould be handicapped in its relationships with other wolves and thus unlikely to become the breeder in a pack.

Breeding dogs for specific behaviors has the potential to distort such checks and balances inherited from their wild ancestors. How do collies feel when they're unable to chase something? Wolves would not be bothered, because they feel an acute need to chase only when they are hungry. But in the collies the connections between chasing, hunting, and hunger must have been broken; otherwise, we could not get them to work safely with sheep. Since these connections have been broken, can we be sure that collies do not perpetually feel a need to chase something? The ease with which they become frustrated when not allowed to work, to the point of displaying stereotypical repetitive behavior, suggests that this is entirely possible. Equally, it is plausible that protection dogs, bred and trained to have heightened sensitivity to challenges, feel anxious and/or angry much of the time, without necessarily displaying any outward signs of these emotions. If such distortions of dogs' natural checks and balances are widespread, and the breed-specificity of many behavioral disorders suggests they are, then

all

breeders, not just show breeders, need to examine what they are doing.