Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood (7 page)

Read Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight: An African Childhood Online

Authors: Alexandra Fuller

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Travel, #Nonfiction, #Biography, #History

Dad on call-up

WAR, 1976

Mum and Dad both join the police reservists, which means Dad has to go out into the bush on patrol for ten days at a time and find terrorists and fight them.

I watch him strip his gun and clean it; it lies on the sitting-room floor in pieces and the house and our clothes and the dogs reek of gun oil afterward. Dad lets me press the magazine full of bullets.

“Faster than that. You’d have to do it a lot faster than that.”

In the back of my cupboard, stacked under my one hanging dress (which is too hot to wear and was sent to me from England by Granny and which smells of mothballs), are the rat packs. Small government-issue cardboard boxes in which there are pink, sugar-covered peanuts, small gooey packets of coffee which leak on everything else, two squares of Cowboy bubble gum, a box of matches, teabags, a tin of bully beef, a packet of powdered milk, sugar, Pronutro. Dad packs five rat packs and a flask of contraband brandy into his camouflage rucksack along with ten boxes of cigarettes.

He puts on his camouflage uniform and he has a camouflage band that Mum made to put over his watch so that it doesn’t blink in the sunlight and alert the terrorists. He paints black, thick paint on his face and arms and when I ask, “Why?” he says, “So the terrs won’t see me.” But he doesn’t blend in. He stands out. He is a white human figure, hunched with the weight of a pack and his gun. He walks with his head down and his legs striding and bandy like a cowboy, without his horse, in a movie. I can see him all the way to the bottom of the driveway when he climbs into the Land Rover that has come to take him away and he doesn’t turn around and wave although I am waving both arms in the air and shouting, “ ‘Bye Dad! ‘Bye Dad!”

I want to warn him that I can see him the whole way down the driveway, that he doesn’t blend in at all. The terrs will easily see him and shoot him. He shouldn’t walk down driveways. I shout, one last thin hysterical message into the hot air, “Don’t let the bugs bite, Dad!”

Mum says, “Shh now. That’s enough.” Dad has heaved his rucksack onto his lap and turned to take a light from a friend for his cigarette. The Land Rover pulls away. As Dad disappears from sight, as the Land Rover jolts over the bump where the snake lives in the culvert at the bottom of the driveway, he raises his hand and I think he’s waving. But he’s just taking a pull off his cigarette.

There’s a lump in my throat that hurts when I swallow and I can’t talk or I’ll start to cry. Mum puts down her hand. She hardly ever lets me hold her hand. I slip my hand into hers and we begin to walk back to the house. It feels strange to hold Mum’s hand and too quickly there is an uncomfortable film of sweat between us. I slip out of Mum’s grip, wipe my hand on my trousers, and run ahead to the house, banging into the warm, meat-smelling, fat-greasy-walled kitchen where July is making bread and the kitchen is becoming rich with the smell of bubbling yeast (which is like the smell of puppy pee).

Mum wears a neat gray uniform—a dress with silver buttons and epaulets and the letters “BSAP” on the sleeve.

“What’s that for?” I finger the letters.

“ ‘British South African Police.’ ”

“But we’re Rhodesian.”

“Mmm.” She tucks her hair under a peaked hat and looks in the mirror, lips crooked the way people look when they are pleased with themselves. “How do I look?”

“Pretty.”

She flashes me a rewarding smile. I am kicking-legs bored on her bed.

Mum tugs a pair of nylon tights onto humid-hot legs and slips into a pair of black lace-up shoes, which look like school shoes.

“Are you a policeman?”

“A police reservist.”

“Oh.”

We drive into Umtali. Mum stops to buy lunch. A sausage roll and a chocolate-covered sponge-cake mouse each from Mitchells the Bakery on Main Street, with a Coke for me.

The police station is out toward the African part of town, in the Third Class district which is less than the Second Class district (with the Indian shops and mosques) and less again, by far, than the distant First Class district where the Europeans shop and live.

There is a small gray duty room for the police reservists, with a wooden desk under a window at which Mum sits. She has brought a book. She sighs, slips off her shoes, and rubs her nylon-covered feet together while she reads. Against the other wall is a thin, narrow bed for the person who will be on duty all night. I sit on the floor nibbling the delicious, flaky, greasy luxury of my sausage roll, working my way through the pastry to the salty meat in the middle. I am in an agony of knowing that the sausage roll will come to an end. But I am also fat with the knowledge that I will have the chocolate mouse next and then my Coke. I make my lunch last, lick by lick, sip by sip, as long as I can. On the wall above the bed there is a chart with the army alphabet on it. After I have finished my lunch I press my back against the cool metal frame of the bed (my belly swollen) and stare at the wall quietly for a long time until the words are completely in my head: “Alpha, Bravo, Charlie, Delta, Echo, Foxtrot . . .” all the way to “Zulu.” I pretend that I have twenty-six horses named after the army alphabet and gallop them around on the bed, my fingers jumping wrinkles and dodging water hazards. Under my breath, “Come on, India. Chtch, chtch. Up we go, boy.”

Next to the bed there is a map of Manicaland with lots of tiny lights dotted here and there.

“What are the lights for?”

“That shows where people live.” She points to where we live; our dot almost spills into Mozambique.

“Why lights, though?”

“If someone gets attacked then they press the alarm on their Agricalert and the light will go off here and I can tell who is getting attacked.”

“What then?”

“I call up the army guys and they go and rescue whoever it is.”

“What if they’re all dead by the time the army guys get there?”

“Don’t ask silly questions.” She goes back to her book.

So I go outside and stare at the jail, which is behind the police station. It is a small gray two-celled building. The cells don’t have windows but there are little slots on the door and in front of the door there are two fenced off yards, like the yards at the SPCA where we sometimes go to rescue dogs to add to the pack. I squint against the sun long enough and peer deeply enough into the doors, and I am rewarded by the startled eyes—very white and staring from the depths of the jail—of an actual prisoner. I smile and wave, the way some people try and get a reaction from a bored animal at a zoo, to see if anything will happen. The eyes blink shut. The face disappears.

I sit under the frangipani tree on the spiky, drying police station lawn with its ring of whitewashed stones and aloe vera flower beds, and I poke pieces of grass into ant lion traps to see the little ant lions leap up with sharp claws in anticipation of an ant meal, which I, and my little piece of grass, are not. Then one of the African sergeants comes out of the police station with trays of food for the prisoners. I lower myself onto my belly, flat against the speckled shadows of the frangipani tree. I don’t want to be told to “go inside now.” The sergeant opens the dog-run gate and bangs on the gray cell doors. The hatches open. The sergeant slides the trays halfway into the mouths of the slots, and they are swallowed into the police cells.

And then Mum comes out and says, “Bobo!” And then, “There you are. Look, you’re all dusty.” She glances toward the prison cells. “Come inside now. It’s time to rest.”

I have to lie down on the prickly gray army-issue blanket for rest time. Mum puts her feet up on the edge of the bed and reads her book. The sound of her breathing, her nylon-covered-foot-rubbing-foot, her gently shuffling pages, and the gathering force of hot-yellow sun are stupefying. And then I am asleep.

In the late afternoon, Mum has finished her book and still no one has been attacked, although I have woken up from my afternoon sleep (dry-mouthed and eyes stinging) and lain on my side for ages staring at the little lights on the map, hoping. The flies are buzzing hotly against the windows and the sun has sunk below the level of the corrugated-tin roof and is sliding breathlessly against the wall with the army alphabet on it (fading Alpha through Golf and Hotel). There is a knock on the door and the police station’s maid comes in with the tea tray (a plate of Marie Biscuits, two chipped mugs, sweet powdered milk reconstituted in a plastic jug, a tub of white sugar, and a small government-issue metal pot for the tea so that Mum immediately asks for more, in anticipation of her second cup).

Mum pours out the tea into the two chipped mugs. Their handles are greasy.

“I hope the prisoners haven’t drunk out of these cups.”

“I’m sure they have their own plastic mugs.”

“What about the other Affies?” I mean the black policemen, the police station’s maid.

“I’m sure they are not allowed to drink out of the same mugs as us.”

“Good.” I dip my Marie Biscuit into my tea and watch crumbs float on the hot, greasy surface.

When we have drunk our tea, Mum reads to me. I lie on the cot under the army alphabet chart. She reads C. S. Lewis’s

The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

Lucy is in the land where it will never be summer, snow crunches underfoot. The sultry afternoon, pale with light-washing sun and the faint hum of traffic from the road that passes the police station all wash into the background. I am transported to a cool snowy world with fawns and witches and Peter and Susan and Edmund and Aslan. I shut my eyes and spread myself out so that my sweating skin can cool; the world of Narnia is more real and wonderful than the world I am alive in.

“Olé!” Mum sings at the club on Saturday night. “I’m a bandit. I’m a bandit from Brazil. I’m the quickest on the trigger. When I shoot I shoot to kill. . . .” She cocks her hip when she sings and sometimes she climbs up onto the bar and dances and shrugs her shoulders, slow-sexy, eyes half-mast, and sometimes she falls off the bar again. But she can’t shoot straight. At target practice she shuts her eyes and her mouth goes worm-bottom tight and she once put a round in the swimming pool wall and another time she shot a pattern, like beads on a string, across the bark of the flamboyant tree at the bottom of the garden. But she has never shot the target in the head or the heart where you are supposed to shoot it.

She taught the horses not to be scared of guns. She burst paper bags at their feet for a whole morning. She popped balloons all afternoon. And the next day she shot guns right by their heads until they only swished their tails and jerked their heads at the sound, as if trying to get rid of a biting fly. So the horses lazily ignore gunshot when we’re out riding, but they still bolt if there’s a rustle in the bushes, or if a cow surprises them, or if they see a monkey or a snake, or if a troop of baboons startles out of the bush with their warning cry,

“Wa-hu!”

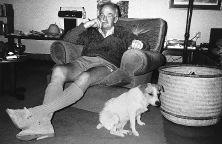

Dad and Pippin

DOG RESCUE

Although Mum actually shot an Egyptian spitting cobra once, and killed it. But that was for real, when her dogs were threatened, which is more serious than target practice.

We are sitting at the breakfast table eating oat porridge. Mum is ignoring my string of questions. She is reading a book and the radio is on. Sally Donaldson hosts

Forces Requests

and plays songs sent in by loved ones for the boys in the bush.

“Yesterday, all my troubles seemed so far away,” I sing along.

Mum says, irritably, “Shhh,” and turns the radio down.

If I peer around the huge stone-wall flower bed Mum has erected to stop bombs and bullets from coming in the dining room window, I can see that Flywell has brought the horses up for our morning ride. I look at Mum. She is absorbed in her book. We won’t get out for a ride until it’s too hot and then we’ll ride until the afternoon, riding through lunch, past the time when my stomach turns and knots with hunger and my throat is burning with thirst and the sun will burn the back of our necks. I will complain of thirst and Mum will say, “You should have had more tea at breakfast.”

I kick the legs of my chair. Mum says, without looking up, “Don’t.” And then, “Eat up.”

But I’ve already eaten up. “Can I have some more?”

“Ask July.”

But before I can get to the kitchen to ask July if there’s more porridge, there is a scramble of dogs from under the dining room table, claws scrabbling on the cement floor before they find purchase and race yapping into the pantry, which is between the kitchen and dining room. Mum looks up from her book. “What have you got?” she asks the dogs.

Three of the dogs retreat sheepishly from the pantry and suddenly Mum says, “Oh hell,” because she can see from their faces and from the sound of their voices that they’re barking at a snake. And then the maid starts to shout, “Madam! Madam!” from the kitchen door and pointing. She has her hand over her mouth, “Madam!

Nyuka!

”

Mum and I stand at the entrance to the pantry and stare in at the snake. Its neck is caped, as wide as a fan, and it’s swaying and tall.

Mum shouts, “Stand behind the table!” She calls the dogs. Shea and Jacko, Best Beloved Among Dogs, are still barking at the snake. “Come!” shouts Mum. She’s loading the magazine. I hear the bullets go in,

clicka-click.

“Come here!” Suddenly the snake rears back and snaps forward and sets out into the air a thin mist of poisonous spray and the dogs come reeling back out of the pantry, yelping and blind, staggering from the pain. Mum lifts the gun to her shoulder. She squeezes her eyes shut and eases back on the trigger. There’s an explosion of glasses and bottles and tins and a wild chattering of bullets. Mum has the Uzi on automatic. She empties an entire magazine toward the snake and then there is dust, the splintering of still-falling glass, the whimpering dogs. Violet, July, and I cautiously creep up behind Mum. The snake is splattered in a red mosaic on the back wall of the pantry along with sprayed beer, and the lumpy contents of tinned beef, tomato sauce, peas. Flour has exploded and has settled peacefully onto the chaos in a fine lacy shroud.

“Madam,” says July admiringly, “but you got him one time!”

By now Shea and Jacko’s eyes have swollen up like tennis balls. Mum screams for milk and July brings the jug from the paraffin fridge in the kitchen. She pours the milk into the dogs’ eyes and they yelp in pain. Mum says, “We have to take them in to Uncle Bill.”

We are not supposed to leave the valley without an armed escort because there are land mines in the road on the way to Umtali and terrorist ambushes and Dad is on patrol, so we are women-without-men, which is supposed to be a weakened state of affairs. But this is an emergency. We put the dogs in the car and drive as fast as we can out of the valley, up the escarpment to the dusty wasteland of the Tribal Trust Land and round the snake-body road which clings to the mountain and spits us out at the paper factory (which smells pungent and rotten and warm) so that when we drive past it as a family Vanessa holds her nose and sings, “Bobo farted.”

“Did not.”

“Bo-bo fart-ed.”

Until I am in tears and then Mum says, “Shuddup both of you or you’ll both get a hiding.”

And now we race past the petrol station that marks the entrance into town and we tear past the gaudy string of Indian stores in the Second Class district where we don’t shop. We bump through the tunnel under the railway line which advertises cigarettes, “People say Players, Please,” and hurry through the center of town, the First Class district, where we

do

shop. Uncle Bill’s veterinary practice is on the other side of town, past the high school. The dogs are crying softly to themselves. Shea is on Mum’s lap and Jacko is on the passenger seat with me.

Uncle Bill says, “You drove in alone?” He sounds angry.

“What else could I do?”

He glances at me, presses his lips shut, and says, “All right. Let me have a look.”

Aunty Sheila says, “Bobo, would you like to come with me?”

I wouldn’t like to go with Aunty Sheila. She has rock-hard bosoms encased in twin-set sweaters. She has hair like a gray paper wasps’ nest.

Mum says, “What do you say, Bobo,” in a warning voice.

So I say, “Yes please, Aunty Sheila,” and she takes me into her perfect sitting room, which leads off the waiting room of the surgery. She tells me to sit-there-and-wait-and-don’t-touch-anything and she goes into the kitchen and comes back with a tray of tea and a plate of food, for which I am grateful, having missed lunch. I am not allowed to eat on the chairs, which are carefully kept clean, with crocheted doilies on their arms. I must sit on the polished floor with the china plate on my lap. Aunty Sheila says, “I don’t have children, I have dogs.”

She has a rash of small spoiled dogs, who are allowed on her beautiful armchairs (unlike me), and some larger dogs who live outside.

I finish my tea and the plate of biscuits and stare at my empty plate meaningfully until Aunty Sheila says, “Would you like another . . .”

And I say yes, quickly, before she can change her mind.

“You’re a hungry little girl,” she says, hardly able to disguise her distaste.

“It’s because I have worms in my bum,” I say, helping myself to a pink vanilla wafer.

We can’t take the dogs home that night. They have to stay with Uncle Bill. When we fetch them a few days later (coming into town in a proper convoy this time), only Jacko is still a little bit blind in one eye.

When Dad comes back from patrol, Mum shows him the pantry and tells him about the snake.

Dad frowns at the shot-up chaos of the pantry, and he says to me, “My God, your mother’s a lousy shot.”

But he wasn’t there to see how wide the snake’s neck was, how it swayed and wove and how its head snapped forward toward the dogs. “I think she’s a jolly good shot,” I say loyally.