Dora Bruder

Â

Dora Bruder with her mother and father

Bruder

PATRICK MODIANO

...............................................

Translated from the French

by Joanna Kilmartin

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

BERKELEY

|

LOS ANGELES

|

LONDON

Â

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses

in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities,

social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation

and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit

www.ucpress.edu

University of California Press

Oakland, California

Â

© 1999 by The Regents of the University of California

Translation © 1999 by Joanna Kilmartin

Originally published as

Dora Bruder

in 1997 by Ãditions

Gallimard, Paris. Copyright © Editions Gallimard Paris, 1997

First Paperback printing, 2015

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

by Joanna Kilmartin.

1926â1942? Â Â Â 3. Holocaust, Jewish

(1939â1945). Â Â Â Â I. Kilmartin, Joanna.

| 940.53'18'092âdc21 [b] | 98-33890 CIP |

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the contribution to

this book provided by the Literature in Translation Endowment

of the Associates of the University of California Press, which

is supported by a generous gift from Joan Palevsky.

Â

Â

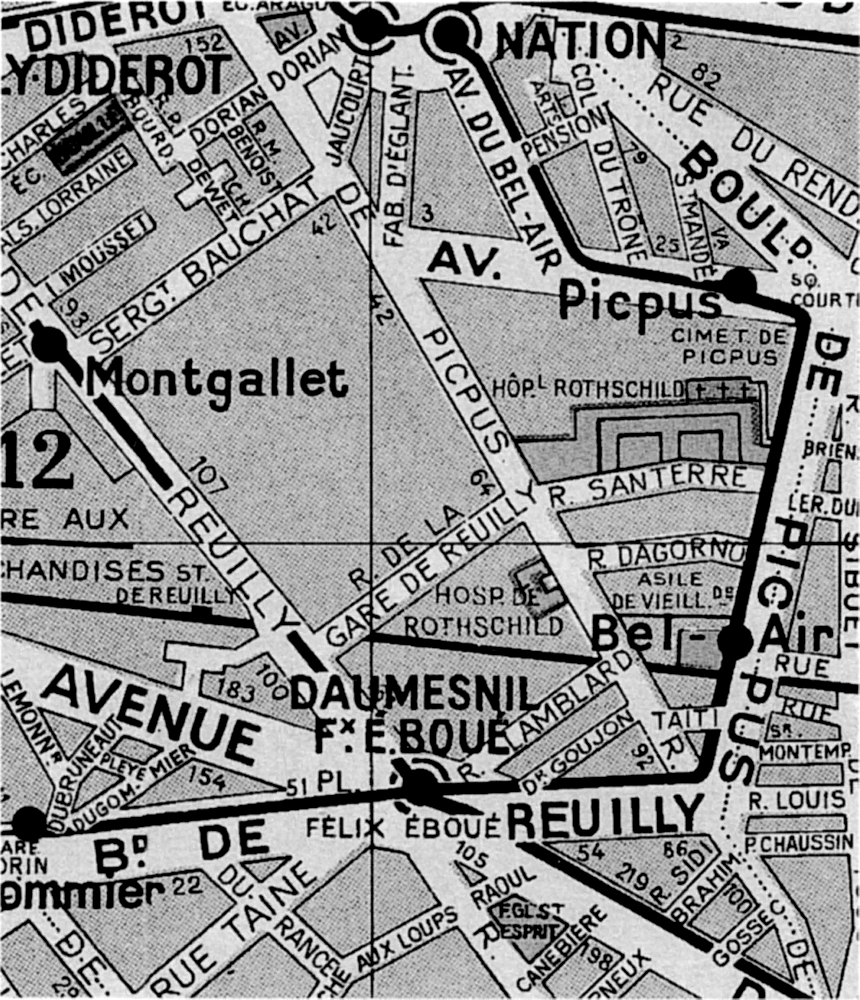

XII

e

Arrondissement (detail)

Â

Â

XVIII

e

Arrondissement (detail)

Dora

Bruder

.................

E

IGHT YEARS AGO, IN AN OLD COPY OF

PARIS-SOIR

DATED

31 December 1941, a heading on page 3 caught my eye:

“From Day to Day.”

1

Below this, I read:

PARISMissing, a young girl, Dora Bruder, age 15, height 1 m

55, oval-shaped face, gray-brown eyes, gray sports jacket,

maroon pullover, navy blue skirt and hat, brown gym

shoes. Address all information to M. and Mme Bruder,

41 Boulevard Ornano, Paris.

I had long been familiar with that area of the Boulevard

Ornano. As a child, I would accompany my mother to the

Saint-Ouen flea markets. We would get off the bus either at

the Porte de Clignancourt or, occasionally, outside the 18th

arrondissement town hall. It was always a Saturday or Sunday

afternoon.

In winter, on the tree-shaded sidewalk outside

Clignancourt barracks, the fat photographer with round spectacles

and a lumpy nose would set up his tripod camera among the

stream of passers-by, offering “souvenir photos.” In summer,

he stationed himself on the boardwalk at Deauville, outside

the Bar du Soleil. There, he found plenty of customers. But at

the Porte de Clignancourt, the passers-by showed little

inclination to be photographed. His overcoat was shabby and he

had a hole in one shoe.

I remember the Boulevard Ornano and the Boulevard

Barbès, deserted, one sunny afternoon in May 1958. There were

groups of riot police at each crossroads, because of the

situation in Algeria.

I was in this neighborhood in the winter of 1965. I had a

girlfriend who lived in the Rue Championnet. Ornano 49â20.

Already, by that time, the Sunday stream of passers-by-outside

the barracks must have swept away the fat photographer,

but I never went back to check. What had they been used for,

those barracks?

2

I had been told that they housed colonial

troops.

January 1965. Dusk came around six o'clock to the

crossroads of the Boulevard Ornano and the Rue Championnet. I

merged into that twilight, into those streets, I was nonexistent.

The last café at the top of the Boulevard Ornano, on the

right, was called the Verse Toujours.

3

There was another, on

the left, at the corner of the Boulevard Ney, with a jukebox.

The Ornano-Championnet crossroads had a pharmacy and

two cafés, the older of which was on the corner of the Rue

Duhesme.

The time I've spent, waiting in those cafés  .  .  . First thing

in the morning, when it was still dark. Early in the evening,

as night fell. Later on, at closing time  .  .  .

On Sunday evening, an old black sports carâa Jaguar, I

thinkâwas parked outside the nursery school on the Rue

Championnet. It had a plaque at the rear: Disabled

Ex-Serviceman. The presence of such a car in this

neighborhood surprised me. I tried to imagine what its owner might

look like.

After nine o'clock at night, the boulevard is deserted. I can

still see lights at the mouth of Simplon métro station and,

almost opposite, in the foyer of the Cinéma Ornano 43. I've

never really noticed the building beside the cinema, number

41, even though I've been passing it for months, for years.

From 1965 to 1968. Address all information to M. and Mme

Bruder, 41 Boulevard Ornano, Paris.

1.

“D'hier à aujord'hui.”

2.

During the Occupation of Paris, Clignancourt barracks housed French

volunteers in the Waffen SS. See David Pryce-Jones,

Parus ub the Third Reich

, Collins,

1981.

3.

“Keep pouring, nonstop.”

.................

F

ROM DAY TO DAY. WITH THE PASSAGE OF TIME, I FIND

,

perspectives become blurred, one winter merging into

another. That of 1965 and that of 1942.

In 1965,1 knew nothing of Dora Bruder. But now, thirty

years on, it seems to me that those long waits in the cafés at

the Ornano crossroads, those unvarying itinerariesâthe Rue

du Mont-Cenis took me back to some hotel on the Butte

Montmartre: the Roma or the Alsina or the Terrass, Rue

Caulaincourtâand the fleeting impressions I have retained:

snatches of conversation heard on a spring evening, beneath

the trees in the Square Clignancourt, and again, in winter, on

the way down to Simplon and the Boulevard Ornano, all that

was not simply due to chance. Perhaps, though not yet fully

aware of it, I was following the traces of Dora Bruder and her

parents. Already, below the surface, they were there.

I'm trying to search for clues, going far, far back in time.

When I was about twelve, on those visits to the Clignancourt

flea markets with my mother, on the right, at the top of one

of those aisles bordered by stalls, the Marché Malik, or the

Vernaison, there was a young Polish Jew who sold

suitcases  .  .  . Luxury suitcases, in leather or crocodile skin,

cardboard suitcases, traveling bags, cabin trunks labeled with the

names of transatlantic companiesâall heaped one on top of

the other. His was an open-air stall. He was never without a

cigarette dangling from the corner of his lips and, one

afternoon, he had offered me one.

Â

Occasionally, I would go to one of the cinemas on the

Boulevard Ornano. To the Clignancourt Palace at the top of the

boulevard, next to the Verse Toujours. Or to the Ornano 43.

Later, I discovered that the Ornano 43 was a very old

cinema. It had been rebuilt in the thirties, giving it the air of an

ocean liner. I returned to the area in May 1996. A shop had

replaced the cinema. You cross the Rue Hermel and find

yourself outside 41 Boulevard Ornano, the address given in the

notice about the search for Dora Bruder.

A five-story building, late nineteenth century. Together

with number 39, it forms a single block, enclosed by the

boulevard, the top of the Rue Hermel, and the Rue Simplon, which

runs along the back of both buildings. These are matching. A

plaque on number 39 gives the name of the architect, a man

named Pierrefeu, and the date of construction: 1881. The same

must be true of number 41.

Before the war, and up to the beginning of the fifties,

number 41 had been a hotel, as had number 39, calling itself the

Hôtel Lion d'Or. Number 39 also had a café-restaurant

before the war, owned by a man named Gazal. I haven't found

out the name of the hotel at number 41. Listed under this

address, in the early fifties, is the Société Ornano and Studios

Ornano: Montmartre 12â54. Also, both then and before the war,

a café with a proprietor by the name of Marchal. This café no

longer exists. Would it have been to the right or the left of the

porte cochère?

This opens onto a longish corridor. At the far end, a

staircase leads off to the right.

.................

I

T TAKES TIME FOR WHAT HAS BEEN ERASED TO RESURFACE

.

Traces survive in registers, and nobody knows where these

registers are hidden, and who has custody of them, and whether

or not these custodians are willing to let you see them. Or

perhaps they have quite simply forgotten that these registers exist.

All it takes is a little patience.

Thus, I came to learn that Dora Bruder and her parents

were already living in the hotel on the Boulevard Ornano in

1937 and 1938. They had a room with kitchenette on the fifth

floor, the level at which an iron balcony encircles both

buildings. The fifth floor has some ten windows. Of these, two or

three give onto the boulevard, and the rest onto the Rue

Hermel or, at the back, the Rue Simplon.

When I revisited the neighborhood on that day in May

1996, rusting shutters were closed over the two end fifth-floor

windows overlooking the Rue Simplon, and outside, on the

balcony, I noticed a collection of miscellaneous objects,

seemingly long abandoned there.

During the last three or four years before the war, Dora

Bruder would have been enrolled at one of the local state

secondary schools. I wrote to ask if her name was to be found on

the school registers, addressing my letter to the head of each:

8 Rue Ferdinand-Flocon20 Rue Hermel7 Rue Championnet61 Rue de Clignancourt

All replied politely. None had found this name on the

list of their prewar pupils. In the end, the head of the former

girls' school at 69 Rue Championnet suggested that I come and

consult the register for myself. One of these days, I shall. But

I'm of two minds. I want to go on hoping that her name is

there. It was the school nearest to where she lived.