Drama (18 page)

Authors: John Lithgow

Coming Home

I

n 1968, my wealthy, childless Uncle Bronson announced that he would make a gift to each of his nieces and nephews of a safe, reliable automobile of our choice. The news of this gift reached me in London. I chose a sturdy, navy-blue VW station wagon, purchased through a dealership in Mayfair. With an eye to the future, I requested a model with its steering wheel on the left side. When I finally sailed home from England on the brand-new

QE2

, my new car was ferried home, too, on a separate vessel. That car would figure prominently in my first weeks back in America.

I was ready to return. The London chapter of my life had been rich, vivid, and fulfilling, and my wife had been gainfully employed there for the entire length of our stay. (Jean, in fact, had found a new vocation: working at a school called “The Word Blind Centre,” she had proved herself to be a wizard at teaching dyslexic children to read.) But not for a moment did we ever consider staying on. In spite of the glories of England, the pleasures of London theater, and the distinctly British coloration of my drama school education, I had a growing sense that an actor was meant to perform for his own native audience. I was desperate to go back and get started. From across the Atlantic, news had reached me of the daring work of Sam Shepard, John Guare, and Megan Terry; of Ellen Stewart’s Café La MaMa and Joe Papp’s Public Theater; of the Living Theatre,

MacBird!

and

Hair

. In fact, the Living Theatre had turned up in London on an international tour. I saw them perform

Frankenstein

at the Roundhouse in Chalk Farm and it blew my mind. Theater like this seemed inextricably tied up with the rush of events back home, and the urgency of those events made me feel more American than ever. The opening words of Buffalo Springfield resonated in my head:

There’s something happening here.

What it is ain’t exactly clear.

“Here” did not refer to England. It was time to go home.

O

n my return, I didn’t exactly dive into the trenches. I went right to work for my father. Several months before, halfway through my second year abroad, I had slipped home to Princeton for a month to direct

As You Like It

for Dad’s McCarter Theatre Repertory Company. On that visit I had come loaded with directorial ideas and rehearsal techniques cribbed from my favorite London productions. The show was the hit of the McCarter season. For me, it had served as a highly successful audition: the company loved performing it, audiences had received it warmly, and I had comfortably navigated the twin challenges of nepotism and overweening youth. As a result, my father was emboldened to offer me an entire season of work at McCarter, his seventh as the company’s artistic director. A letter from him arrived at our London flat. In a quaint blending of formality and fatherly affection, he laid out his terms:

January 29, 1969

Mr. John Lithgow

61 Onslow Gardens

London S.W. 7

ENGLAND

Dear John,

Your letter home has bugged me into writing an official sort of communication that I have been too slow in getting off.

In the first place, the production of

As You Like It

has been a great success at many levels. The general public and the student public has been delighted. The Shakespeare Establishment on the faculty seem ecstatic (after all, the obscure material on the allowed fool has remained uncut, unlike most productions). And, most rewarding perhaps, the Company loves to play it. Furthermore, our august Committee itself has initiated enquiries about your availability for next year.

Naturally, I have never entertained any doubts about your artistic and productive capabilities. Indeed, my main concern about my own dilatoriness was what I have thought the likelihood that you would be making commitments to the theatre there in London which would obviate a possibility here at McCarter.

While there are good psychological reasons why you should go off on your own for your next professional step, thoroughly objective good sense can be found in offering you an important rank on the McCarter artistic staff next season. The particular emphasis in acting, design, and directing, the details, the draft problems or its interference—all of these can wait upon conversations. You can go on the payroll as early as July 1st, if certain assignments are attractive, and you could count on at least $150.00 per week.

At any rate, give us an opportunity to compete with other offers which might be upcoming for you. I’d be interested in a structuring of your own particular interests at this time.

Affectionately, but officially,

Dad

In subsequent conversations, my father outlined his plans for me. He proposed that I direct and design two productions and play major roles in several others. It would be my first time working under an Actors’ Equity contract, an eight-month job that perfectly suited my triple-threat ambitions. Considering my age and inexperience, it is inconceivable that any other regional theater producer would have made me such an offer, but I ignored the implicit favoritism. My father asked and I accepted. I rushed home in midsummer, 1969, to help him staff up for the coming year. Jean stayed behind in London for another month to finish her teaching commitments, and I went right to work.

My first McCarter assignment was a solitary one. At the wheel of my newly imported blue station wagon, I drove out of Princeton to visit summer-stock companies all over the Northeast. The trip was to be a random search for young talent, with special attention paid to set designers. I hit the road with a list of theaters, a pocketful of McCarter cash, and no specific itinerary. This proved to be unwise. For days I wandered New England like the Ancient Mariner, clocking hundreds of miles and nodding through woefully inept summer-stock shows in sweltering, barnlike playhouses, fanning myself with my program and ducking the nosedives of the occasional bat. The only designer prospects I spotted were “highly desirables,” long since committed to other jobs.

After my first few stops I became convinced of the futility of my mission. But I pressed on anyway. In fact, I was having a pretty good time. New England was green and gorgeous in the mid-August sunshine, and I reveled in my solitude. I was still in a transitional mode between two worlds, reacquainting myself to the States. Having been away for two long years, I was a twenty-three-year-old Rip Van Winkle, keenly attuned to how much the country had changed since I’d left. Radicalism was being subtly incorporated into the culture. The long hair, torn jeans, head bands, beads, and tie-dyed T-shirts of the hip young had created a new aesthetic, very different from the Kings Road modishness of London. Images of smiling, assimilated African-Americans were all over TV and billboard advertising, an astonishing change from two years before. The car radio blared with the exuberant defiance of Hendrix; Joplin; Crosby, Stills, and Nash; and Country Joe and the Fish. These were the sights and sounds of a changed America, and I drank it all in. But if I felt the giddy excitement of a returning prodigal, that excitement was tempered by the nagging awareness of all that I’d been missing.

On a Thursday, I left the town of Stowe, Vermont, having sat through a threadbare production of

The Apple Tree

there the night before. Heading south, I had chosen the Taconic Parkway, a route that took me through upstate New York, alongside the Massachusetts border. I was thinking that I might catch an evening performance of the American Shakespeare Festival at Stratford, in southern Connecticut. But I hadn’t decided for sure, and I was in no particular hurry. When I stopped at a café for lunch, I overheard a conversation at the cash register about a three-day music festival that was just getting underway in the area. Back in the car, I heard even more about it from a radio disk jockey. Several of the very groups I had been listening to were expected to perform. I began to notice a proliferation of VW microbuses on the road, spray-painted in rainbow colors and packed with funky, long-haired young people. I surmised that they must be heading to that festival I’d been hearing about.

“This might be interesting,” I thought. “Maybe I should go.”

I sized up my situation. My wife was on the other side of the ocean. I’d spent hardly any of my expense-account money. I had no set schedule and no immediate obligations. My talent-scouting trip was yielding no results. I could easily spare three or four days. And even if I couldn’t find a place to stay, I could always sleep in the back of my station wagon. Jimi Hendrix? Richie Havens? Joan Baez? The Grateful Dead? The Who?

“Three days of peace and music”? Sounds great.

Why not?

. . . Naaaah!

I kept driving that day. By evening I was sitting by myself in a stuffy crowd, watching

Henry V

in Stratford, Connecticut. A few days later I was back in Princeton, reporting dutifully to my father on my fruitless mission. I thereby missed out on one of the most pivotal moments in the history of rock and roll, three days that would come to define my generation. I missed Woodstock.

What if I’d made an abrupt right turn and headed to Max Yasgur’s farm that afternoon? What if I’d heard all that music, smoked all that dope, and done all that acid? What if I’d danced in the rain, played in the mud, and screwed stoned-out girls in the back of my car? What if I had rebelled against the careful orderliness of my life—my tidy marriage, my dutiful job, my accommodating father, my “art”? What if, for one weekend, I had broken loose? Such speculation is pointless, of course. I would never have done any of those things. It simply wasn’t me. My orderly life was a response to the disorder of the years that had gone before. The only moments of rebellion I allowed myself were playacted moments onstage, with all my lines written out for me. I would rebel all right, but it wouldn’t be for several more years. And when it happened, it wouldn’t be at a music festival.

The Triumph of Nepotism

L

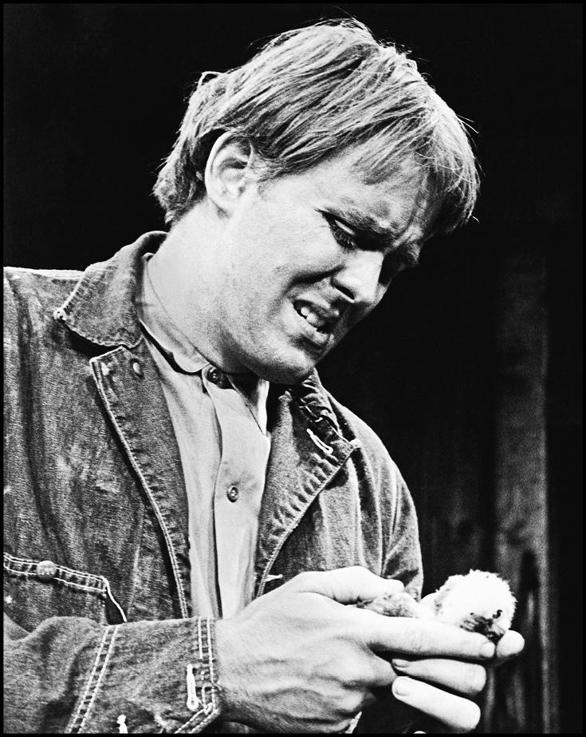

enny in

Of Mice and Men

? Were they crazy? When I was cast as Lenny at McCarter, I thought the idea was insane. I was still scarecrow thin, and still affected the dandified airs of a fresh-faced LAMDA alumnus. These were hardly the qualities anyone would associate with Lenny, the lumbering, feeble-minded San Joaquin Valley migrant in John Steinbeck’s Depression-era yarn. The role was first played onstage in 1937 by Broderick Crawford, a beefy, beetle-browed character actor who couldn’t possibly have been more different from me. But there were no Broderick Crawfords on hand at McCarter that year, so who else were they going to cast? I was half a foot taller than the next-tallest actor in the resident company, so with height as my only asset, the role of Lenny fell to me.

I’d never dreamed of playing such a part. The notion scared me to death. But I was about to learn a lesson that would echo repeatedly throughout the coming years: the most exciting acting tends to happen in roles you never thought you could play. Writers, directors, and producers tend to picture you differently than you picture yourself. They sometimes have more faith in you, and more imagination. This can be a very good thing. An actor is often much better off as the subject of other people’s brainstorms. When I was cast as Lenny, I was the only person in the building who didn’t think I could handle the part. Surprise! It ended up being my best performance yet.

Of Mice and Men

was scheduled to open in tandem and run in repertory with George Bernard Shaw’s

Pygmalion

. The Shaw was to open first. In that show, I was on more familiar ground: I was cast in the chatterbox role of Henry Higgins. The virtuosic double act of the flighty Higgins and the earthbound Lenny saddled me with a backbreaking workload. But there was more to come. The third offering of the season was to be Shakespeare’s

Much Ado About Nothing

, which I would both design

and direct.

With a swiftness and confidence that verged on the foolhardy, my father had made me a major player in both the acting ensemble and the directing staff of his company. Barely pausing to look this gift horse in the mouth, I dived right in.

So began the first official chapter of my career in American theater. It might have been titled “The Triumph of Nepotism.” But if Dad had given me the meatiest, most coveted assignments of any member of his company, the other actors didn’t seem to object. With fond memories of my production of

As You Like It

the year before, they warmly welcomed me back into their midst. Or at least they appeared to. In retrospect, I suspect that this courtesy was merely skin-deep and may have masked a considerable degree of show-me skepticism. I had two enormous parts to learn and a big production to design, so I wasted no time worrying about their envy or doubt. But when I lost my voice and the opening night of

Pygmalion

was cancelled (an inauspicious start to my professional career), my fellow company members could have been forgiven for feeling a sweet, collective rush of schadenfreude

.

Photograph by Jim McDonald. Courtesy Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

O

f Mice and Men

suffered no such setbacks. It was a remarkable journey from beginning to end, full of startling, revelatory moments. The production was staged by a journeyman actor-director several years my senior named Robert Blackburn. Bob had first known me years before when he was acting for my father at the Antioch Shakespeare Festival. I was seven years old at the time. Directing me in a leading role must have been an odd adjustment for him. But if he still saw me as that skinny kid hanging around rehearsals, he managed to get past it. He rolled up his sleeves and methodically set out to transform me, piece by piece, into the hulking Lenny. He ordered up padding from the costume shop to add heft to my torso. He had me wear elevator insoles inside my heavy work boots to make me loom even larger. He prescribed a regimen of weightlifting to make my upper body ache and to slow my movements. He attached weights to my ankles to hobble my gait. As the rehearsal days passed, my thought processes gradually slowed down. So did my speech. Henry Higgins’ crisp chatter gave way to Lenny’s stammering plainsong drawl. I stepped out of Shaw’s Wimpole Street parlor and into Steinbeck’s dry Dust Bowl world. I felt like Lenny to the life.

The two shows opened within weeks of each other. They were well received by critics and crowds alike, and company morale was high as we began to perform both of them in repertory. For me, alternating between two such different roles was exhilarating, especially since the challenge had seemed so insurmountable when I had begun. Best of all, I keenly sensed that, long after I’d left school behind, I was learning more about acting than ever. Creating a believable Lenny, so distant from me in every conceivable way, had been a thrilling breakthrough, broadly expanding my sense of what I could do. But the biggest lessons I would take from

Of Mice and Men

were yet to come. And those lessons would come from an extremely unlikely source.

McCarter Theatre, you see, had student matinees. This was a tradition begun by my father a decade before, in his job as McCarter’s education coordinator. The program had expanded considerably over the intervening years. Still booming today, it is now named after him, and a plaque in McCarter’s lobby memorializes his early commitment to it. Then as now, thousands of high school kids from all over New Jersey arrived in bright yellow school buses throughout the season, to attend matinees of all the McCarter productions. Of the theater’s yearly offerings, familiar chestnuts and high school English-class standbys tended to be the plays most heavily scheduled. One of these, of course, was

Of Mice and Men

. And we were slated to do a dozen performances of it for teenage kids.

By the time we faced our first student audience, we’d already performed the show several times for adults. Puffed up by rave reviews and loud ovations, we were pretty full of ourselves. If grown-ups are so moved by

Of Mice and Men

, we thought, just imagine the response of sensitive young kids. They will love this! There won’t be a dry eye in the house! We were about to see fresh evidence of just how thoroughly actors are capable of deluding themselves.

The play, of course, is the story of Lenny and George, two itinerant fruit pickers in a work gang on a California truck farm in the bleak 1930s. The two are a symbiotic pair, traveling and working together year-round. Lenny is big, powerful, and retarded, with an infantile weakness for anything soft and furry. Like a child in his parent’s care, Lenny is lost without George. His shy, childlike nature makes him a touching, gently comic creature, but it conceals a scary, almost unconscious capacity for violence. George is constantly alert to this, and has learned to control Lenny by feeding him fantasies of a farm of their own, “with rabbits.” But on a couple of occasions, Lenny’s violence comes out. He kills a puppy when it won’t stop barking. He crushes the hand of a taunting foreman named Curly. And in a horrific scene near the end of the play, he strangles Curly’s wife when she resists his innocent attempts to stroke her soft, golden hair. Knowing that Lenny is doomed once he is apprehended, George administers a nighttime mercy killing in the final seconds of the play. As Lenny kneels in a dry riverbed, dreamily intoning his ritual description of the farm they will someday own, George stands behind him and fires a bullet into his head.

It is a play full of tenderness, melancholy, and horror. The first time we performed it for kids, they thought it was screamingly funny.

And Lenny was the most hilarious thing they’d ever seen. I was literally laughed off the stage. I’d always adored the sound of laughter from an audience, and by that time I’d heard plenty of it. But I’d never heard the jeering, mocking, ear-splitting laughter of those kids. It rained down on me in torrents and drowned out the play. They laughed loudest at the moments I had considered the most delicate, tender, and moving. Rabbits? Hysterical. A dead puppy? A riot. Curly’s wife? A hoot! And at the end, when George held the pistol to Lenny’s head, some class clown out in the darkness shouted, “Go ’head! Shoot ’im!” and a crowd of a thousand teenagers exploded. It was a moment of horror, all right, but not the one we had been looking for.

The shrieks of laughter carried over into the curtain call. After my last grudging bow, I stormed into the wings and stood there in the darkness, shaking with humiliation and rage. As I listened to the happy jabber of the kids clambering out of the theater, I cursed every last one of them at the top of my lungs. Then an appalling thought abruptly silenced me:

I have to do this

eleven more times

!

I wouldn’t have to wait long. A few days later we performed our second

Of Mice and Men

matinee for kids. I had been anticipating it with misery and dread. But at the same time a gritty determination had set in. There was no way out. I had to face the screaming mob. But this time, I was determined to avoid another cascade of taunts and guffaws. I decided to challenge the teenage audience to a kind of theatrical chess match. More by instinct than calculation, I set out to make tiny adjustments every time I came to a moment that had triggered laughs the last time around. I overlapped cue lines, rushed through pauses, mumbled some provoking phrases and buried others altogether. The process was like tiptoeing through a minefield or plugging leaks in a dike where laughter had gushed in. Only a few of these strategies worked. There were still plenty of moments where the young audience got away from me and ran roughshod over a scene like an unbroken horse. But it happened less often. There were fewer laughs, I was less cranky, I had a clear sense of where the trouble spots still lay, and I had begun to savor the challenge.

In each succeeding student matinee, I eliminated a few more unwanted laughs. I also discovered a few laughs that were worth keeping. Adjusting the humor, pathos, and horror of the play became a game of strategy and intrigue. Each show was an onstage laboratory where the experiments became increasingly complex and daring. I began to realize that kids—so spontaneous, restless, and impudent—were the ideal focus group for a piece of theater. If you are inauthentic, excessive, or boring onstage, an adult audience will rarely protest. Out there in the darkness, they will cough, shift in their seats, stare at their programs, roll their eyes, or nod off. The only way they register their displeasure is by merely applauding at the curtain call with slightly less enthusiasm (when did you last hear someone actually boo an actor?). But kids? When kids think something is dull, fake, corny, square, gauche, or inept, they’ll let you know it. They’ll riot. But if you can keep their attention and reach into their hearts, you know you’ve really achieved something.

By our last

Of Mice and Men

matinee, we had learned to cast a spell over an audience of teenage kids. They laughed all right, but only when we wanted them to. And when we wanted them quiet, you could hear a pin drop. They followed every turn of the plot, every ebb and flow of emotion. They listened intently and leaned forward in their seats to hear every syllable of every scene. All through the final terrible moments of the play, we could hear muffled sobs out in the house. And when George raised his pistol behind Lenny’s head, we would once again hear the occasional cry. But now the cry was “Don’t do it, George!” shouted out through tears. This time, it was a cry from the heart.

And here’s the point. During those weeks, we also performed

Of Mice and Men

several times in the evening for grown-up crowds. By the end of our run, the show had greatly improved. And I believe it was the student matinees that had improved it. We hadn’t learned all that much from the adults who had come to see us, but those kids had taught us volumes.