Dreamers of a New Day (37 page)

Read Dreamers of a New Day Online

Authors: Sheila Rowbotham

[Naxos] had grown into a machine. It was now a show place in the black belt, exemplification of the white man’s magnanimity, refutation

of the black man’s inefficiency. Life had died out of it. It was . . . only a big knife . . . cutting all to a pattern, the white man’s pattern. Teachers as well as students were subjected to the paring process, for it tolerated no innovations, no individualisms.

60

By the late 1920s social, economic and political factors had converged to raise doubts about the cluster of assumptions which had fuelled the efforts to change how everyday life was lived. Nevertheless, the dreamers and adventurers who from the 1880s had questioned so many aspects of women’s destiny had also raised fundamental questions about the economy as a whole. Implicit within their condemnation of relationships of inequality were challenges to the organization of economic and social existence. They were prepared to interrogate the labour process, the domination of machine technology, a prosperity based on the expanding consumption of individual commodities. Some desired an entirely new way of producing and consuming; others a more humane capitalism. Some wanted labour to be recreated as art, others to minimize labour time to allow for more leisure. Some demanded more state; others less.

En route, they controverted accepted ways of seeing, demolishing the demarcations imposed upon thought. Paid labour connected to livelihood; production expanded into life; creative humanity defied the machine; the personal stress of the ‘telephone girl’ illuminated the flaws of an economic system. Divided they might be; pusillanimous they were not.

10

Democratizing Daily Life: Redesigning Democracy

In 1913, the recently founded

New Statesman

magazine produced a special supplement on ‘The Awakening of Women’, the title echoing that of Kate Chopin’s 1899 ‘new woman’ novel. Charlotte Perkins Gilman was one of the contributors, and Beatrice Webb wrote the Introduction. The ‘awakening’, insisted Webb, had to be seen in much broader terms than simply the political struggle for the vote, or even feminism. A wider women’s movement existed which, she believed, was related to the international movement of labour and ‘unrest among subject peoples’. Webb recognized that women in this wider movement were challenging not only gender but other relations of subordination. Struggling to express how awareness had emerged through participation in social movements, she suggested that theoretical ‘schemes of reform’ had combined with ‘heroic outbursts of impatient revolt’ to generate the ‘cross-currents of method and immediate aim’.

1

The British working-class socialist and feminist Hannah Mitchell describes just such a moment of epiphany in her autobiography,

The Hard Way Up.

One day in the mid-1890s, while listening to a ‘callow youth’ in a Methodist chapel debate hold forth on how Adam, Saint Paul and Milton had all agreed that women should not take part in politics, bottled-up resentment had caused her to spring to her feet in fury. Congratulating ‘our “young friend” on his intimate knowledge of the Almighty’s intentions regarding the status of women’, she suggested that he broaden his reading to include ‘more democratic poets’. Mitchell ‘then flung at him and the meeting a chunk of my recently acquired Tennyson. “The woman’s cause is man’s; they rise or fall together”’. As she sat down in some confusion there was ‘applause from the women present’, and the ‘sex prejudice’ contingent ‘lost much of its self-assurance’.

2

Across the Atlantic, Anna Julia Cooper quoted exactly the same line from Tennyson in

A View from the South

(1892), when testifying to the cross-currents of personal experience which brought black women into social action.

3

Both Mitchell and Cooper knew about oppression from their own lives and both had to struggle against the silence which was expected of them. The books they loved helped them to counter bigotry.

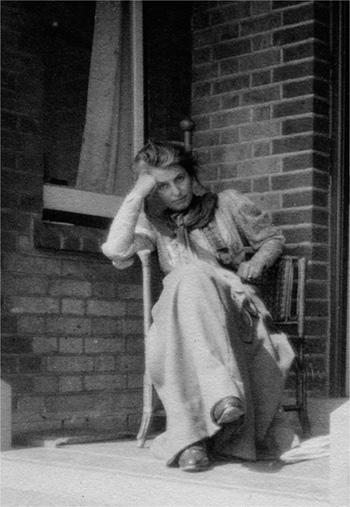

Beatrice Webb, ca 1900 (Passfield Collection, Library

of the London School of Economics)

The tensions women faced around the prevailing demarcations of public and personal activity galvanized resistance. If they were alerted to wider ideas and other forms of subordination, this subjective rebellion could extend outwards. Women who had experience of organizing within a range of social movements came to see relationships between diverse causes. Frances Ellen Harper, who had been active in the anti-slavery movement, women’s suffrage and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, told the National Council of Women in 1891 that racial subordination in the United States was akin to anti-Semitism. She went on to challenge imperialism and the class system: ‘Among English-speaking races we have weaker races victimized, a discontented Ireland and a darkest England.’

4

This empathetic understanding of interconnecting injustices, combined with women’s own efforts to break through the cultural barriers they encountered, could foster a holistic approach to social citizenship which extended into all aspects of existence. In Britain a delegate to the 1915 Co-operative Congress, Guildswoman Mrs Wimhurst of Woolwich, summed up how one thing led to another: ‘Social reform consisted of things that merged together; it could not be chopped into sections’.

5

Such awareness did not, however, do away with inequalities, divisions and prejudices which remained within the movements for change. These presented tremendous obstacles for women who sought to stake out their own rights as citizens while democratizing daily life and relationships. Faced by a white suffrage movement concerned to mollify white Southerners and a male-dominated black movement, Anna Julia Cooper retaliated with a cultural concept of African-American female power: ‘Only the BLACK WOMAN can say “when and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole

Negro race enters with me

.”’

6

Cooper ingeniously adapted an idea of women as harbingers of a new social order present within early nineteenth-century

radical thought, giving it a political edge which challenged not only the complacency and prejudice in white women’s organizations but also the chauvinism of some male black leaders. In 1898 Mary Church Terrell, speaking at the National American Woman Suffrage Association, took a slightly different tack, presenting black women as playing a special redemptive role: ‘With tireless energy and eager zeal, colored women have, since their emancipation, been continuously prosecuting the work of educating and elevating their race as though upon themselves alone devolved the accomplishment of this great task.’

7

Anna Julia Cooper (Oberlin College Archives, Oberlin)

Nevertheless, in practice the defining of entry points proved to be a daunting and often divisive Catch-22 for both white and black women. Mrs Wimhurst might state proudly that for members of the Women’s Co-operative Guild, co-operation and citizenship were indivisible, but radicals and reformers alike kept coming up against a frustrating dilemma.

8

If they stressed that they had a specific contribution to make as women, they could be enclosed within restrictive and externally defined limits; but when they sought to transcend the gender divide by laying claim to universal human rights, their particular demands could be

passed over. Dreamers in very different situations discovered that their efforts to democratize daily life required a parallel project of redesigning democracy.

A determined attempt was made to combine the universal and the particular in a gendered redefinition of social citizenship. This was not simply an abstract affair: it involved confronting the issues through practice. The first paid organizer for the Women’s Co-operative Guild, Sarah Reddish, who had begun her working life aged eleven as an outworker winding silk, stood as a candidate for Bolton Town Council in 1907 on the grounds that ‘Work on town councils was human work, and why should work for humanity be confined to one sex?’

9

In 1894 Reddish mustered her experience as a politically active working-class woman in a concerted challenge to the assumed divisions of who did what and who belonged where:

We are told by some that women are wives and mothers, and that the duties therein involved are enough for them. We reply that men are husbands and fathers, and that they, as such, have duties not to be neglected, but we join in the general opinion that men should also be interested in the science of government, taking a share in the larger family of the store, the municipality and the State. The WCG has done much towards impressing the fact that women as citizens should take their share in this work also.

10

Reddish cut through the domestic/female – /files/05/36/57/f053657/public/male divides head-on by raising men’s role in the home alongside women’s position in the social and political sphere. She also rejected the argument that women’s familial duties debarred them from asserting individual claims.

The need to affirm women’s autonomy by creating a woman-friendly form of social citizenship brought a gendered slant to contemporary debates pitting individualism against collectivism. In 1899 Enid Stacy, who had followed Helena Born and Miriam Daniell in organizing women workers in Bristol, attempted a synthesis of individual and social claims in her essay on ‘A Century of Women’s Rights’. She looked forward to the time when ‘Women’s Rights’ would be replaced by the broader human aim of securing ‘to each human being such conditions as will conduce to full development as an individual and a useful life of service to the community’. Stacy tried to balance individual and personal rights with public, political rights and duties. This is how she detailed them:

1. As individual women. The right to their own persons, and the power of deciding whether they will be mothers or not. . . .

2. As wives. Perfect equality and reciprocity between husband and wife. This necessitates legal changes, notably as regards the Law of Divorce; e.g., whether the law be made laxer or more stringent it must affect both sexes alike.

3. As mothers. Guardianship of their children on the same terms as in the case of fathers . . .

11

Stacy’s fourth claim was for full political citizenship and her fifth for women as workers. This final category caused a certain difficulty for her. She asserted that the ultimate aim was ‘a co-operative commonwealth’, ensuring ‘to each citizen, irrespective of sex, a choice of employment indicated by the results of education and only limited by individual capacity.’

12

More immediately, within the capitalist system of production, she believed it was the duty of the state to protect motherhood for the future. Though legislation at work would cover men as well as women, specific measures should take into account the needs of ‘women as mothers prospective and actual’.

13

From the 1890s onward, the collectivist assumption that the state had a duty to protect women’s reproductive capacity would be associated with demands for social resources to enable mothers to mother better. Such claims converged from dissimilar sources: eugenicists, imperialists, social-purity campaigners and philanthropic reformers could be aligned with liberal and socialist women. Motherhood campaigners agitating for social citizenship brought with them differing conceptions of the state. The divisions between reformers and radicals were never completely hard and fast; broadly, however, reformers were inclined to regard the existing state as morally improving or as embodying modernizing efficiency, while those radicals who wanted state intervention on behalf of mothers held that the rights of mothers as citizens constituted an extension of democracy, and so implied a critique of the existing state.