Drinking Water (11 page)

Nor was dangerous water only in army camps. In many cultures, the most effective strategy to avoid unsafe drinking water has been to

avoid water

altogether. Part of this aversion was for safety’s sake, but there was a snobbish motive, as well. As a classical scholar has

described, the Roman elite regarded water as “the characteristic drink of the subaltern classes, the cheapest and most easily available drink, fit for children, slaves, and the women who had been forbidden from drinking wine very early in the Republic.”

This aversion to water carried into the Middle Ages. In the time of Charlemagne, high-ranking military officers were punished for drunkenness by the humiliation of being forced to drink water. In the fifteenth century, Sir John Fortescue observed that the English “drink no water unless it be … for devotion.” The sixteenth-century English doctor William Bullein warned that “to drinke colde water is euyll [evil]” and causes melancholy. His contemporary Andrew Boorde claimed that “water is not holsome soole by it self; for an Englysshe man … [because] water is colde, slowe, and slack of dygestyon.” Presumably, water interfered with digestion by cooling the stomach and its furnace-like operation.

The eighth-century author Paul the Deacon recounts a wonderful anecdote showing the relative prestige of wine and water. A nobleman’s enemies planned to kill him and chose the method of poisoning his wine chalice. As dinnertime approached, they eagerly waited for him to raise the poisoned goblet to his lips. The canny nobleman, however, had suspicions about the wine and foiled the plot by surprising everyone. Instead of drinking wine with his meal, as everyone had expected, he drank water, a liquid so common and beneath his standing that no one had even considered poisoning it. Stooping beneath his station to drink water instead of wine saved the canny nobleman’s life.

The aversion to water carried over to the New World, as well. As Francis Chapelle has described, despite readily available water in New England, the Pilgrims sought other drinks.

Drinking water—any water—was a sign of desperation, an admission of abject poverty, a last resort. Like all Europeans of the seventeenth century, the Pilgrims disliked, distrusted, and despised drinking water. Only truly poor people, who had absolutely no choice, drank water. There is one thing all Europeans agreed on: drinking water was bad—very bad—for your health.

If not water, then what did people drink? The answer in ancient times often was alcohol. The drink of choice in Egypt was beer, and in ancient Greece wine. It may not be surprising that one of the very first buildings constructed in Plymouth Plantation was a brewhouse.

More common, though, was a mixture of water with another substance. Sometimes this was alcohol. The fifth-century Hippocratic treatise “Airs, Waters, Places” recommended adding wine to even the finest water. Beer was routinely added to water (called “small beer”) in the Middle Ages. Water was also commonly mixed with vinegar, ice, honey, parsley seed, and other spices. This both improved the taste and served as a status symbol. The mixtures elevated the status of what otherwise would have been a common drink. After the discovery of the East Indies, mixing hot water with coffee and tea became popular.

It is interesting to note that none of these mixing practices was consciously intended to make the water safer to drink, though this often may have been the result. Alcohol added to water retarded and even killed microbes. While India Pale Ale may now be all the rage in microbreweries, the addition of hops was originally intended to preserve ale in the hot colonial outposts of India (unbeknownst to the brewers, it slowed bacterial growth). Boiling water for tea and coffee would have had a similar effect.

Despite the preference for alcohol over water, water was always drunk, sometimes as plain water but often in the cuisine. Soups, stews, and dried foods were commonly prepared in water. Indeed, in the Middle Ages, more water may have been consumed in a household through prepared foods than drunk. So the question remains, how did those searching for drinking water know the source was safe? Long before recognizing the role or even the existence of microorganisms, people have understood that they need to be careful about what they drink. Over time, different groups’ collective experience of identifying safe water has developed into unwritten rules, oral versions of a safe drinking water act. Importantly, however, these practices focused primarily on the

source

of the water because that was all they could observe.

The ancient Greek father of medicine, Hippocrates, for example, wrote that water from rock springs was “bad since it is hard, heating in its effect, difficult to pass, and causes constipation. The best water comes from high ground and hills covered with earth.” Perhaps the greatest water engineers of all, the Romans, designed their aqueducts to segregate drinking water from other uses. The chroniclers of the time debated over which waters should be most prized. Pliny the Elder favored well water, while Columella preferred spring water. Disparaging the choice of the very wealthy, Macrobius counseled against drinking melted snow because it no longer contained water’s healthy vapors.

Europeans recognized, as well, that certain water sources should be avoided. William Bullein warned in the sixteenth century, for example, that “standing waters and water running neare unto cities and townes, or marish ground, wodes, & fennes be euer ful of corruption, because there is so much filthe in them of carions & rotten dunge, &

c

.”

Nor are such practices purely historical. A recent study of villages in Yorubaland, a region in southwestern Nigeria, examined how safe water is identified in traditional African communities today. Just as the Romans and Europeans developed rules to identify safe water, the Yoruba believe that when water comes from the mountains it has a sacred origin and, therefore, it has many qualities that other streams lack. Because a rock represents a mountain, also any water springing under a rock of these streams is believed to be safe. Similarly, rainwater is always regarded as safe because it comes directly from heaven. The local people give movements of flowing water a strong emphasis. They say that it is easy to

see

if the water is clean and good for human consumption. Flowing water is regarded safe, as the movements will take dirt away.

In fact, all societies have such rules and practices to identify safe water sources, though they may look very different. In a number of cultures, for example, drinking water is as much a spiritual as a physical resource—water can transmit both physical

and

metaphysical contaminants. As a result, there are specific rules to prevent spiritual pollution of drinking water. Traditional Hindus in India,

for example, maintain a complex social hierarchy among separate castes. Reinforcing this order, upper and lower castes actually draw their water from distinct sources. If sources were shared, there would be a risk of the lower caste transmitting their social pollution from the impure to the pure. This extends to food preparation. A Brahman should not even touch food that has been prepared with water by a non-Brahman.

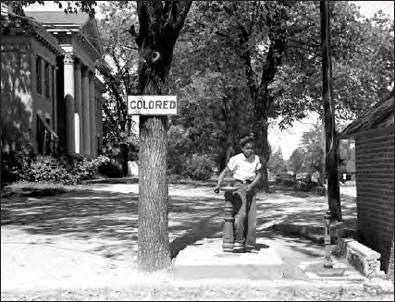

In the United States this practice should look familiar. Less than fifty years ago, resource segregation was commonplace in many parts of the South. Drinking fountains were separated by law, with one for “White” and one for “Colored.” This was accepted as entirely justified under the law. While half a world away, was the anxiety some whites felt over drinking from a fountain that had been used by blacks all that different from the Hindi concern of higher castes drinking from the same sources as lower castes?

A drinking fountain on the Halifax County courthouse lawn in North Carolina, 1938

Most of these rules intuitively seem to make sense. We can see if water comes from fast-flowing waters and appreciate why it would be safer to drink than water from a stagnant pool. By contrast, the Safe Drinking Water Act seems light-years from these sorts of norms. The EPA is currently assessing the adverse health effects of the microbe

Helicobacter pylori

and the chemical 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene. This hyper-technical approach could not seem more distant from checking whether water emerges from under a rock or whether the person who used the well before you was an Untouchable. Yet these sets of rules all seek the very same end—safe drinking water from a trusted source, whether faucet or stream—and they all make sense to their respective societies. Such norms are essential and they are effective, to a point. Indeed, if such rules have endured over long periods of time, almost by definition they have to work; otherwise, the society that followed them would have been incapacitated by waterborne diseases. The Yoruba preference for clear, flowing water makes some sense in a modern light. It avoids the higher microbial activity in warmer, stagnant water.

Assessing

how well

such rules work, though, is a complicated matter. To assess that, we need to understand how popular conceptions of disease influence our perceptions of water quality. If water from a particular source is regarded as unsafe, locals have clearly made the connection between drinking the water and some bad result—such as spiritual impurity, blindness, or stomach cramps. But there must also be a causal mechanism lurking beneath this judgment. Today, one might say that people get typhoid because they drink water with

typhoid bacteria

, of course. But before the microscope revealed an entirely new world beyond our eyes, for most of human history physicians grappled with the problem of people getting sick without any physical contact at all with ill people.

With our modern understanding of disease, we may look patronizingly on earlier practices of bloodletting or of locating latrines next to wells, but before the era of the germ theory, these seemed entirely reasonable in their respective societies. In fact, cultural understandings of what causes disease, whether physical or spiritual, underpin the rules for drinking water.

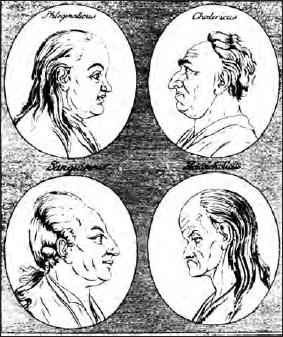

An eighteenth-century French illustration by Johann Lavater shows how these humors were expressed in physical features: phlegmatic in the upper left, then, moving clockwise, choleric, melancholy, and sanguine

.

At the time of the Greeks and Romans, for example, physicians believed that the health of the body depended upon the balance of four humors: black bile, yellow bile, phlegm, and blood. Each humor was linked to specific physical qualities. Blood was warm and moist, while black bile was cold and dry. Hence Bullein’s admonition that drinking cold water was evil. Its chill risked slowing the flow of humors and could cause melancholy. Indeed the name of one particularly virulent waterborne disease, cholera, comes from the term for yellow bile, “choler.” “Sanguine,” equally, came from the humor of blood (“sang” in French), and “phlegmatic” from the humor of phlegm. The task of the physician was to diagnose the illness and deduce the surplus or deficit of each humor causing the ailment. He could then nurse the patient back to proper balance and health. Thus the common practices of bleeding a person or using emetics were both intended to remove surplus humors.

This conception was eventually supplanted by the miasmatic theory of disease. This theory held that diseases were caused by breathing contaminated air. The general concept was that an airborne mist containing poisonous “miasma” served as the agent of disease and could often be identified by its foul odor. Hence the name for malaria, which means “bad air.” This theory explained how people could quickly infect one another without physical contact, as well as the awful stench surrounding diseased flesh. Although an inaccurate explanation, the miasma theory was effective. Its immediate policy implication—improved cleanliness—no doubt reduced the spread of pathogens.

A moment’s reflection makes clear the consequences of the miasmatic theory of disease for how people thought about drinking water. If the most threatening diseases—epidemics such as bubonic plague, cholera, and typhoid—were airborne, then drinking water was unlikely to be a serious cause of concern. This is not to say, of course, that people were ignorant of the link between drinking water and disease. People obviously could get sick from drinking certain types of water, but not from the most feared epidemics. The drinking water was safe enough, just not risk-free, to use modern parlance.