Due Diligence (7 page)

Authors: Michael A Kahn

“Congratulations.”

“We're going to get married as soon as he gets back from Brazil.”

“When's that?”

“Next December. I can't wait.”

“Is he down there on business?”

“No, he's on a mission.”

“Really?” I said uncertainly.

She noticed my expression. “For the church.”

I recalled the Utah posters in the living room. “Ah, the Mormon Church?”

She nodded. “William's on a two-year mission in Brazil. It's already been more than a year.”

As she ate dinner, we made small talk about life in Brazil and her wedding plans. Karen Harmon was an easy person to like: cheerful, outgoing, and warmhearted, with a bright, generous laugh. Almost reluctantly, I brought the conversation around to the purpose of my visit.

“I met with Hiram Sullivan yesterday morning,” I said.

“Mr. Sullivan?” she said. “Really?”

I nodded. “He wasn't willing to tell me much about Bruce.” I explained my interest in Bruce Rosenthal's death and my concern that it might be linked to another death. “Bruce was upset when he called me,” I continued. “He wanted to talk to a lawyer. I think it had something to do with his work. Something he had discovered, probably about a client.”

Karen nodded seriously. “Okay.”

“Was he working on many matters the last month or so?”

Karen thought it over. “No,” she said. “I think he was spending most of his time on the SLP deal.”

“Good.”

“Really?” She looked surprised.

“It narrows the hunt,” I explained. “I was afraid you were going to tell me there were dozens of different matters.”

“Well,” she said with a frown, trying to remember, “there may have been one or two small projects, but nothing big. It was mostly SLP. If he was billing time to other projects, they'd show up on his time sheets. If it helps, I could check them for you.”

“That would be great, Karen. Thanks.”

“Sure,” she said with a smile. “Actually, you're starting to get me kind of curious.”

I shrugged good-naturedly. “It's contagious. You said he was working on the SLD deal.”

“P, not D. SLP.”

“What is it?”

She gave me an embarrassed look. “I'm not exactly sure.”

“Is it confidential?”

“Oh, no. It's been in the newspapers, I think, or at least the

Wall Street Journal

. I know, because Bruce had me make copies of some articles from the

Journal

. SLP is a foreign company. French, I think. Its initials are SLP.”

“Was your firm doing work for them?”

She nodded. “They're buying a company or a division of a company here. It's called Chemitoc, Chemitac, Chemi-something.”

“Chemitex Bioproducts?”

She smiled. “That's it.”

“What was Bruce doing on the deal?”

“Some of the due diligence.”

“Ahh,” I said with a knowing smile.

Due diligence

. Utter that dull gray phrase around a pack of corporate lawyers and watch them leer. That's because the final tab for the due diligence in a significant transaction will easily exceed ten million dollars. Those kinds of numbers enchant even the most somber of practitioners.

Due diligence is the stage in every corporate acquisition between the handshake and the closing, between the engagement party and the wedding vows, between that press release announcing the deal and the day the New York Stock Exchange opens with one less listed company. Due diligence is what squadrons of lawyers, accountants, and other specialists do to the books and records and the assets and liabilities of the target company during the months before closing. Think of it as a massive and extraordinarily expensive physical, with the target company face down and naked on the examination table for weeks, or even months. Usually, the patient checks out fine, and the deal goes through. But occasionally the head of the due diligence team removes his rubber gloves, steps out in the hallway, and grimly reports to the board of directors that, in the words of Gertrude Stein, his team has discovered that there is no there there, or even worse, that there is something rotten in the division in Denmark. That's when the spin doctors put out the carefully worded release explaining that, after lengthy and careful consideration, the board of directors had concluded that the goal of maximizing shareholder value blah blah blah.

“Where was Bruce doing the due diligence?” I asked.

“In town. Chemitex is south on Hampton Avenue. Bruce spent a lot of time down there over the past two months.”

“What sort of due diligence?”

“I'm not sure. You see, he was a chemical engineer

and

he was an accountant. Sometimes they had him do engineering stuff, sometimes accounting stuff, sometimes both.” She raised her eyebrows. “He was really smart.”

“What kinds of things did you do for him?”

“Some typing, some filing, answering the phonesâyou know, secretary stuff. I had two other bosses, too. It keeps you busy.”

“Did he have you do any typing or filing on the SLP deal?”

She frowned in thought. “Not much typing. Just an occasional dictation tape or letter, but that's all. He had a laptop computer that he took with him everywhere. As for filing, he kept his SLP documents in the file drawers in his office and did most of the filing, but I helped keep them organized.”

“Was that typical?”

“Sort of, at least on the big due diligence projects. When they're over, I usually have to type up all the reports and memos to the file, but I don't do much while they're still going on. That's 'cause the guys are usually out of the office reviewing the documents at the business site.”

“Is the SLP deal still going on?”

“Oh, yes. Definitely.”

“Are there others at the firm working on it?”

“I think three others. But none of them had Bruce's background.”

“What do you mean?”

“He was the only chemical engineer working on it. He was the only one reviewing the drug files.”

“Is someone taking over his part of the due diligence?”

“I don't think so. At the end of last week I was told to pack up his files and ship them off to the lawyers for SLP.”

“Did anyone tell you why?”

She smiled at my naïveté. “No one tells secretaries why. But I asked around 'cause I was curious. I heard that SLP decided to have its own scientists review Bruce's files instead of postponing the whole deal to wait for another chemical engineer to get up to speed. It would have taken a long time. Bruce had been working on it for almost two months.”

“Did Smilow and Sullivan save a copy of Bruce's due diligence files?”

She shook her head. “There were thousands of documents.” She paused, her forehead wrinkling in thought.

“What is it?” I asked.

“I don't know,” she said tentatively. “He missed three days of work before we found out he was dead. None of us knew anything was wrong at first. I thought maybe he was busy down at Chemitex and too busy to call. Anyway, I went into his office that first day to straighten up.” She paused. “His due diligence files were a mess.”

“That was unusual?”

She nodded. “Definitely. Remember, Bruce was an engineer

and

an accountant. He kept everything in that office neat and organized. That's why I remembered about those due diligence files. I straightened them as best I could. I thought to myself that maybe he came in that morning real early looking for something in a big hurry and made the mess. At least, that's the way it lookedâlike someone searching for something in a big hurry.”

“Was anything missing?”

“I wouldn't have been able to tell, Rachel. There were so many documents to begin with, including a bunch written in scientific gobbledygook. I tried to put the files back together that first day. Bruce didn't come in the next day. That's when I started to get nervous. Finally, Mr. Sullivan had us report him missing. The police talked to me. I answered their questions, told them what he was working on, showed them his office. I was really worried by then. Having the police there made it seem serious. After they left, I went back into his office to look around. The first thing I noticed were those due diligence files.”

“What?”

“They were messed up againâeven more so than the first time. Maybe the police did it, but I don't think so.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Nothing else in his office was messed up. Just those darn files.”

“What kind of documents were in those files?”

“A real mishmash. Bruce's work papers and spreadsheets, of course, and then gobs and gobs of photocopies of company documents. That's how Bruce did due diligence on these deals. He would go down to the company, dig into their files and start tagging documents to be copied. Hundreds of documents. Then he'd come back to the office with all those copies and stay there till midnight sorting them and marking them up and arranging them in different folders and typing notes and comments on his laptop.”

“Do you remember what kind of documents he copied?”

She shrugged. “Not specifically. They were mostly the usual types he'd copy when he did due diligenceâmemos, lab reports, scientific stuff, correspondence, financial records.”

I leaned back, trying to make sense out of what she had noticed about the state of his files. According to the police detective I had spoken with earlier that day, Bruce Rosenthal had most likely been assaulted in the firm's offices late at night and then shoved into the trash chute, feet first. Judging by the extent of the fractures in his leg bones, he had fallen a good distance, which meant he probably had been dumped into the trash chute opening on the Smilow & Sullivan floor.

There was, I realized, an innocent explanation

and

there was a far darker one for the condition of Bruce's due diligence files. The innocent explanation was that Bruce himself had messed up his files the first time, looking for something in a rush, and the police had messed them up the second time. The darker explanation was that whoever killed Bruce had gone into his office the first time, probably right after he dumped the body down the chute, looking for a specific document or, more likely, a specific group of documents. A day or two later, the killer discovered that he may have missed one or more of the key documents, so he sneaked back into the office to search again.

I looked at Karen. She was wiping her eyes. “Are you okay?”

She nodded her head, sniffling. “I was just thinking about poor Bruce. He wasn't real friendly, but he never did anything nasty to me. And even if he had, no one deserves to die that way.”

I handed her a tissue. When she got her emotions back under control, she made us both some herbal tea. We took our mugs to the living room.

I took a sip of tea and asked, “During the last few weeks, did he mention any concerns or worries?”

She shook her head. “No.”

“Where did Bruce keep his due diligence notes?”

“Mostly in his laptop computer. He took it with him just about everywhereâto job sites, to meetings out of the office, on business trips. Sometimes he dictated his notes into one of those portable recorders. But when he did that, he always had me type them up right away. He'd make corrections and have me copy the corrected version onto a disk so that he could load it into his computer.”

“Did he ever have you do that on the SLP deal?”

“A few times.”

“Do you remember what you typed?”

“No, but I might recognize it if it's still in his computer.”

“Where is his computer?”

“Probably at the office.”

“Really? The police didn't take it?”

She shook her head. “We made them a copy of everything on the hard drive. I heard that Mr. Sullivan didn't want them to take the computer. Those things cost thousands of dollars, you know, and he's a real penny-pincher.”

I leaned forward. “Karen, do you think you could get me a copy of whatever files are in his computer?”

“Well,” she said hesitantly, “I guess so.”

“Maybe there's something in there that will tell us what he was so worried about.”

“I can try tomorrow,” she said.

I took out one of my business cards, wrote my home phone number on it, and handed it to her. “This is my office number, and this is my home number. Don't tell anyone at the office why you want his computer files. If you get asked, have a cover story ready.”

“Okay.”

“One last thing,” I said, reaching into my briefcase. “There was a list Bruce gave my friend. I'm not sure what it is, but maybe you typed it for him. Or maybe he found it on his SLP due diligence. Here's a copy.” I handed her the list. “I have the original.”

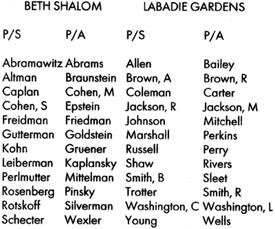

I came around behind so that I could look at the list too: