Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (21 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

In fact, since its initial publication, Elton’s interpretation has been systematically demolished by historians. A great deal of careful work has shown that many of Cromwell’s Tudor revolutionary reforms were not Cromwell’s but Henry’s or some other government official’s; not Tudor but anticipated by the Yorkists; therefore not revolutionary but evolutionary; or not true reforms but power grabs by one government office or another fighting for turf and fees. Above all, historians have found no evidence of a Cromwellian master plan to turn the Crown administration into a modern bureaucracy; rather, he was perfectly content to pursue his goals through old institutions like the household and informal arrangements if they served his purposes. And yet, it is impossible to deny that, in the wake of the break from Rome,

something

remarkable, even, perhaps, revolutionary, was happening in England in the 1530s and 40s.

Take the issue of sovereignty, the location of the ultimate power in the state. For Elton, the key to the Tudor Revolution was the relatively new and rather modern notion that sovereignty and, therefore, the loyalty of the subject, should reside in one person and office: that of the king. Parliament had said as much in the preamble to the Act in Restraint of Appeals of 1533 when it called England “an empire… governed by one supreme head and king.” In this context, the word “empire” does not mean a vast expanse of territory. Rather, it here derives from the Roman concept of

imperium

: the power to give commands and have them obeyed without fear of contradiction. What this meant to Henry, Cromwell, and their contemporaries was that the king owed obedience to God alone; his people to God through the king alone. Since no other human being could judge or command or contradict the monarch in England, his subjects had no room for countervailing loyalties to the pope, the Church, the local landlord, county, or town, as in the old, feudal system. Except for the Roman pontiff, who was now a virtual non-person in England, all were subordinate to and therefore answerable to the king. According to Elton, this crucial piece of legislation went far to articulate the idea of the modern nation-state, with impermeable borders and allegiance to one sovereign power.

17

But note that this legislation was not a royal decree but an act of parliament, one of the series of statutes by which Henry VIII assumed control of the Church. Thus, if England was an empire ruled by a supreme head and king, that king was, nevertheless, not absolute. The Tudor monarchy was, in some sense, limited by laws, and Henry VIII showed some regard for Parliaments, defending members from arrest and allowing some measure of free speech. As he himself once said: “we at no time stand so highly in our estate royal, as in the time of parliament.”

18

This does not mean that Henry intended to share his imperial sovereignty; both he and Cromwell regarded Parliament as a tool. So why would a man of Henry’s imperious nature have said such a thing? Why would a loyal servant such as Cromwell have embraced it? Perhaps because both men realized that, in pursuing radical solutions to the king’s and the nation’s problems, they needed at least the appearance of support, of governing with the kind of consent that Henry VII had won, and so many previous Lancastrian and Yorkist rulers had not. In short, Henry and Cromwell needed partners to push through their legislative program.

But in securing Parliament’s partnership, Henry had, perhaps inadvertently, increased its role and, therefore, its potential power. Parliament had, since the Middle Ages, exercised the right to approve or disapprove of taxation. After 1529, the king asked this body to legislate not only on religion, but, as we shall see, on a wide variety of social and economic matters. For the moment, Parliament remained the junior partner because Henry was such a commanding presence and because Cromwell, unlike Wolsey, was an effective parliamentary manager. But their expansion of Parliament’s role would, in future reigns, provide that body with a justification for continuing to discuss these matters whether the monarch liked it or not. Henry and Cromwell had thus laid the seeds for a debate about sovereignty by creating the potential for conflict between a later, weaker, king and his newly empowered and increasingly experienced legislature. Future generations would play out this conflict at great cost.

In the meantime, Cromwell sought to make Henry’s

imperium

effective over his whole empire. To do that, he had to make English government more efficient and responsive to the king’s wishes. To do

that

he had, in his view, to make himself more powerful. Cromwell’s official position was king’s secretary. His influence with the king allowed him to make this position the most important in Tudor government, superseding Wolsey’s old post of lord chancellor. Indeed, Cromwell may fairly be credited with creating the basis for the later office of secretary of state. Professor Elton also gave him the credit for increasing the speed and flexibility of the council by reducing its membership to about 20, plus a clerk. But recent work indicates that this smaller, more effective “privy council” was actually created by the king as a counterweight to Cromwell’s power.

Cromwell also reformed the king’s finances. In 1537 he asked all the revenue departments to declare their income and expenditure and state the balance available for the king’s use; prior to this, the government’s accounting procedures were so antiquated that the monarch almost never knew how much money he had. Cromwell also reduced the jurisdiction of the Exchequer by placing the king’s finances into the hands of a series of four courts whose procedures were ostensibly more rational and efficient.

19

But these measures also increased the secretary’s patronage and control of the royal purse-strings. Finally, as master of the king’s Jewel House, Cromwell had effective control of Henry’s personal funds via his access to the royal coffers. Thus, the ad hoc nature of household finance was not so much eliminated as placed in Cromwell’s hands.

Henry and Cromwell sought not only to make the king’s government more responsive at the center; they also tried to make it more effective in the localities by giving hundreds of local gentry honorary positions at court and by eliminating all authorities and affinities but the sovereign’s in the country. Most of the territory ruled by the king of England was remote from London; much of it was virtual borderland (see Introduction). We have seen how the harsher climates and more rugged terrain of the North, West Country, Wales, and Ireland tended to favor smaller and more isolated settlements, which, in turn, implied less integrated economies, extended kin loyalties, and domination by a few nobles or clan chiefs prone to rivalry and violence. Such areas were difficult to control from the center. In fact, there were still some areas in England, called franchises or liberties, in which the king’s writ did not run at all because some local aristocrat or bishop had long ago been granted freedom from royal jurisdiction. For example, in the county palatinate of Durham, the sheriff and JPs served in the name of the bishop of Durham, not the king. In the Marches of Wales, courts ruled in the name of the Marcher lords, not the king. Even in those remote areas where the king claimed sovereignty, he often had to rely on a single powerful nobleman both to keep a lid on local violence and to defend the frontier from hostile foreign intruders. Such noblemen tended to be cooperative only when it was in their interest to be so. If that interest dictated otherwise, as in the case of the Nevilles under Henry VI and Edward IV, or the earl of Kildare under Henry VII (see chapter 1), they might just as easily rebel against their master in London. It was Cromwell’s goal to tame such areas and their inhabitants, both noble and common.

For example, the Henrician regime sought to solve the problem of northern violence by displacing the Percies, Nevilles, and Dacres following their dubious performance in the Pilgrimage of Grace, in favor of strengthened institutions. First, Cromwell secured an act of parliament abolishing the independence of the county palatinates of Chester and Durham. At about the same time, the childless Henry Percy, earl of Northumberland (ca. 1502–37) was persuaded to make the king his heir, eliminating at one blow the power of a leading northern magnate family while enriching the Crown’s holdings. Finally, Henry revived and strengthened the Council of the North to watch over that area and to respond to the frequent skirmishing that occurred along the Scottish border.

Even more than the North, Wales was a patchwork of jurisdictions. The king was its greatest landowner and its northern part, the principality of Wales, was, in theory, ruled directly by the prince of that name. But since the title “prince of Wales” was usually taken by the king’s son, it was vacant for most of Henry’s reign. The south, especially the English frontier known as the Marches, was administered by about 130 powerful, but not always cooperative, Marcher lords. The lawlessness of Wales was due not only to fragmentary jurisdiction but also to long-smoldering hostility between the native, rural Welsh population and English settlers in urban areas. Nor did it help that Welsh law was relaxed about physical violence and rights of inheritance.

20

In 1536 Cromwell initiated a radical solution: a series of laws abolishing both the principality and the Marcher lordships as governmental authorities, replacing Welsh law and language in the courts with English law and language, and dividing all of Wales into 12 shires with lords lieutenant, JPs, MPs, and circuit courts along English lines. The Welsh Acts of Union (1536–43) also eliminated many distinctions and penalties which had made the Welsh second-class citizens in their own land. Finally, Cromwell strengthened the Welsh Council of the Marches, appointing the “hanging bishop” of Coventry and Lichfield, Rowland Lee (ca. 1487–1543) its president. He earned this nickname by allegedly executing 5,000 rebels, cattle-thieves, and other felons between 1534 and 1540.

These measures produced mixed results. They strengthened the king’s authority, but violence (either among English nobles or between them and the Scots) continued in the North. In Wales the news was better: violence subsided and the ruling elite, particularly the South Wales gentry who purchased former monastic lands (see below), began to integrate more fully into English government, economy, and society. At the same time, the Welsh gentry and people remained faithful to their culture and language, even if the Marches and southern Wales were bilingual. Perhaps as a result, bitterness at being a colonized people died out among the Welsh of the early modern period. Welsh separatism would only resurface in the twentieth century.

Bitterness has, of course, long characterized relations between the English Crown and Ireland. It will be recalled that Ireland had been colonized by English settlers since the Middle Ages. That incursion upon the native Irish, or Gaelic, population had been supported by the Crown and the English king was, technically, overlord of all Ireland. But English power had been in steady decline since about 1300. By 1485, it was restricted to an area around Dublin known as the Pale.

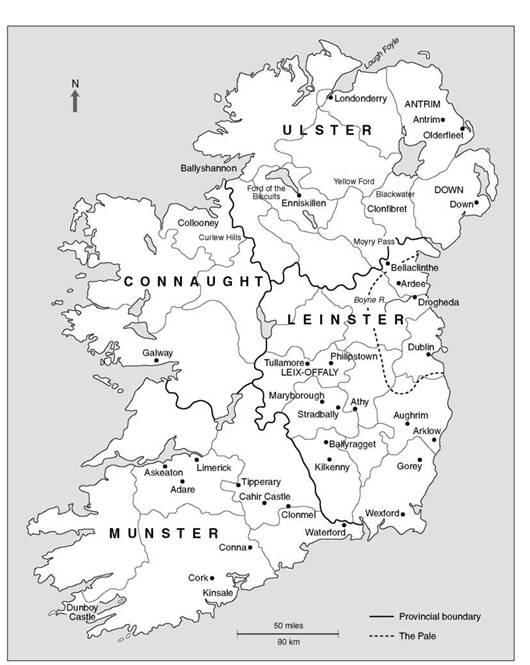

Map 7

Early modern Ireland.

Within this area, a parliament largely made up of Anglo-Irish landlords, sat; but from 1494 (see below), it could only debate measures previously approved by the king and council. The rest of Ireland may be divided, first into the so-called “obedient lands” to the south and east of the Pale, ruled by Anglo-Irish nobles descended from the original English colonizers; and second, “wild Ireland” to the north and west, which was dominated by rival Gaelic septs, each headed by a great chieftain (see

map 7

). No English king had any power over the “wild Irish,” who were traditionally looked upon as savages by their Anglo-Irish neighbors. Nor could the king always count on the loyalty of the Anglo-Irish peers, who had increasingly overcome their distaste to embrace Gaelic customs and culture, and even marry into the Gaelic septs. Though the obedient lands were divided into shires and theoretically owed their loyalty to the Crown, in practice, the Anglo- Irish peerage tended to behave like the Marcher lords of Wales or the North. That is, they fought for advantage among themselves, sometimes enforcing the king’s writ, sometimes making common cause with Gaelic chieftains whom they were, ostensibly, supposed to keep down.

Of these Anglo-Irish peers, the most powerful were the Fitzgeralds, earls of Kildare. Under the Yorkists, successive earls of Kildare had been granted vast estates and given the authority that went along with the title lord deputy of Ireland. It was to them that royal power was delegated – to protect the Pale, to maintain order in the obedient lands, and to pacify wild Ireland, if possible. But, as we saw in the case of the eighth earl’s support of Lambert Simnel and flirtation with Perkin Warbeck, the Fitzgeralds proved inconsistently loyal. In 1494 Henryremoved Kildare from the deputyship in favor of an Englishman, Sir Edward Poynings (1459–1521), who forced the Irish Parliament to assent to the restrictions of

Poynings’s Law of 1494

(necessary because that body had supported the various pretenders) and an army to enforce them. But armies are expensive and unpopular and so, in 1496, the Tudors turned back to Kildare, who remained an uncertainly loyal lord deputy until his death in 1513. His successor as ninth earl and lord deputy, another Gerald Fitzgerald (1487–1534), did not always agree with royal policy, but he continued to maintain a fragile peace in the king’s name, building up a vast affinity through marriage alliances with the Gaelic septs. This rendered him more effective as the king’s lieutenant, but it also made him imperious, over-confident, somewhat resented by other, less powerful, Anglo-Irish families – and much harder to control or replace from London.