Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History (77 page)

Read Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History Online

Authors: Robert Bucholz,Newton Key

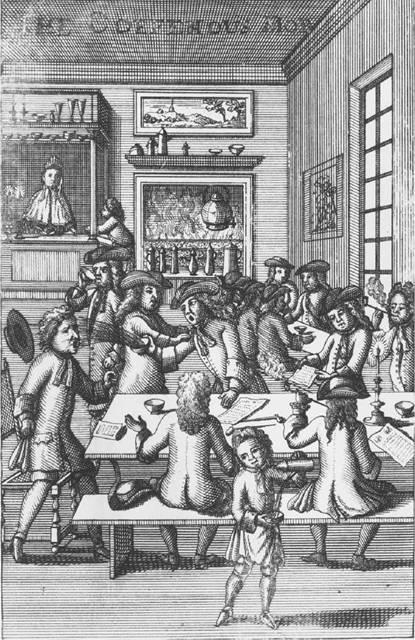

Plate 25

Fighting in a coffee-house after the trial of Dr. Sacheverell. © British Museum.

Finally, the Whigs managed to offend the queen on the issue of sovereignty. Anne had turned to the Whigs as her allies in fighting the war. But she had never really warmed to them, in part because they did not treat her with the traditional reverence for monarchy. As will be recalled, she had sought to govern by appointing the best men of both parties. But the Junto had other ideas. Knowing full well that the queen needed their expertise and parliamentary support to fight the war, they demanded a clean sweep of Tory officeholders. Anne resisted “the five tyrannizing lords,” as she called them, for years, continuing to employ moderate Tories like Harley as one of her secretaries of state. In February 1708, after it became clear that Anne and Harley might try to construct a government without the Junto, Marlborough, Godolphin, and the Whig leaders forced the secretary’s dismissal by threatening their own mass resignation. This deprived the queen of the one minister who had counterbalanced Junto ambitions. Later that year Anne’s beloved husband, Prince George, died, and with him some of Anne’s stomach for the fight. By late 1709 every Junto lord but Montagu (now Halifax) held office, and there were few or no Tories left in government. The queen seemed a pawn in Whig hands, forced to put up with a ministry she did not like, a war she no longer supported, and attacks on the Church she loved.

The Queen’s Revenge, 1710

In fact, as the year 1710 dawned, it became clear that Anne had had enough. She began to consult secretly with Harley through the hands of a number of her court attendants, most notably a woman of the Bedchamber named Abigail Masham (1670?–1734). Masham’s duties were those of a lady’s maid, necessitating close personal attendance on the sovereign. Because of Anne’s poor health, Masham was at her side constantly as a virtual nurse. Fortunately for Harley, her sympathies were Tory and she was more than willing to be a go-between.

In the meantime, Anne had grown estranged from her Whig favorites, the Churchills. Her friendship with the duchess had soured because of Sarah’s constant pushing of the Whig point of view. Her friendship with the duke had taken a turn for the worse when, in the previous year, she had refused his request to be made captain-general for life. Blaming these reversals on Masham’s influence, in January 1710 the Whigs considered moving for a parliamentary address to the queen demanding Abigail’s removal from court. To Anne, this was the ultimate act of

lèse-majesté

, for it took out of her hands the right to appoint her closest and most personal servants. In order to stop this move, she canvassed peers and MPs of all political persuasions, sometimes “with tears in her eyes.”

18

During similar meetings in March, she took the opportunity to indicate that while she agreed with Sacheverell’s guilt, she did not want to see him punished harshly. Clearly, Anne was attempting to undermine her own ministry. The monarchy still had enough prestige that many peers and MPs, including some Whigs, did the queen’s bidding on both issues: the address to dismiss Masham was never moved and Sacheverell was convicted, but punished lightly.

These victories gave Anne courage. In April she began to sack Whigs, starting with her lord chamberlain, a Junto ally named Henry Grey, marquess of Kent (1671–1740). In June she attacked the Junto directly, removing Sunderland as secretary of state. In August she dismissed Godolphin as lord treasurer. He was succeeded by a Treasury Commission whose most influential member would be Robert Harley. From this point Harley was, in effect, the queen’s principal minister, though he would not receive the staff as lord treasurer and the title earl of Oxford until the following May. Harley is often seen as a Tory but this does not mean that he intended a Tory ministry. Throughout the summer of 1710 he worked hard to undermine the Junto while keeping moderate Whigs in the ministry: after all, the queen did not want to exchange a Whig ministry for a Tory one but to restore the balance between the two. But party loyalties were too strong. Few Whigs would work with Harley and he had no hope of presiding successfully over the current Whig-dominated Parliament. And so, in September 1710, the queen dissolved Parliament. The resulting election was a referendum on the war and Whig fiscal and religious policy. The Tories, running on a platform of peace with France, low taxes, and the defense of the Church of England, won the majority of seats in a landslide. The brief Whig ascendancy under Anne was over.

The Treaty of Utrecht, 1710–13

Queen Anne, Robert Harley, and their supporters had gone to the country with, first and foremost, a promise of peace. Even before his appointment, Harley had begun secret negotiations with the French. The Whig minority in the new Parliament opposed the peace every step of the way, charging that any treaty that allowed the duke of Anjou to remain on the Spanish throne would be a sellout after so many victories and so much blood and treasure expended. It would also betray Britain’s allies, since none of them would want to agree to the ensuing treaty. Partly because of Whig resistance and the intrigues of the Allies, the peace took two and a half years to negotiate. It was won only after much shady dealing on both sides. For example, in December 1711, the Whigs betrayed one of their guiding principles by promising the dissident Tory Daniel Finch, earl of Nottingham (1647–1730), that they would vote for a bill against occasional conformity if he would persuade other Tory peers to oppose the peace. Anne countered by creating 12 pro-peace Tory peers to outvote the Whigs. Many contemporaries thought this an unseemly stretching of her prerogative. Even more unseemly was the queen’s treatment of Marlborough and the Allies. She dismissed the former in December 1711 after it became clear that his military aggressiveness threatened the peace negotiations. Then she issued “restraining orders” to his replacement, Ormond, so as not to embarrass Louis. Now it was the turn of the Allies to feel that the British were not doing their part, that “perfidious Albion” was selling them out to the French.

On the surface, the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713 does, indeed, appear to be a sellout. For starters, Britain agreed to Anjou’s ascent to the Spanish throne as Felipe V. This was qualified only by a provision stipulating that the French and Spanish crowns could never be united in one holder. The Allies received territory, but not so much as Marlborough’s and Eugene’s victories would seem to have promised. The Dutch were awarded a series of forts on their southern border to form a barrier against France. According to the later Treaty of Rastadt (1714), the Holy Roman emperor received significant Spanish territory in Italy as well as what had once been the Spanish Netherlands, thus forming a further buffer between the French and the Dutch. Savoy claimed Sicily. As for the British, at Utrecht they acquired Gibraltar and Minorca in the Mediterranean; Nova Scotia, Newfoundland, and Hudson’s Bay in Canada; St. Kitts in the Caribbean (see

map 14

); and the Asiento, an agreement which guaranteed British slave traders the exclusive right to sell human beings to the Spanish Empire for 30 years as well as other trading rights with the Spanish colonies. Finally, the French promised to recognize the Hanoverian succession and withdraw support for the Pretender. The Whigs thought these acquisitions small potatoes after the earth-shaking victories at Blenheim and elsewhere. They thought Louis’s promises to recognize the Hanoverian succession, withdraw support from the Pretender, and refrain from uniting the French and Spanish crowns worthless, for he had broken similar promises before. In the next reign they would revenge themselves on Oxford and other Tory peace negotiators by impeaching them in the House of Lords.

They should not have done so, for Utrecht was, in fact, a master stroke of British diplomacy. It demonstrated clear-eyed realism about the European situation as it was; and prescience about what it would be in the future. First, the Spanish settlement could not have been otherwise after the Allied defeats at Almanza and Brihuega. The Spanish people wanted “Felipe V.” Moreover, the Allied candidate for the Spanish throne, “Carlos III,” the Archduke Charles, had become the Holy Roman emperor in April 1711 upon the death of his brother. To endow him with the Spanish Empire would be to replace an over-mighty French Bourbon state with an over-mighty Austrian Habsburg one. In any case, Oxford realized what the Whigs did not: that it did not matter who sat on the throne of Spain. France was too weak, economically and militarily, after two decades of war either to unite the two crowns or to profit much from their unity. Nor could the Bourbons do much for the Jacobite cause. French power was broken, whether the treaty said so or not.

Moreover, the economic provisions of the treaty would ensure that, during the long period of peace while the French licked their wounds, the British would grow wealthier and more powerful. While Gibraltar may be a tiny rock, whoever possessed it controlled the trade between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. Nova Scotia and Newfoundland may be bleak and remote, but they were a foothold in Canada, and they offered the rich fishing of the Grand Banks. The acquisition of another island in the West Indies (St. Kitts) meant that, thanks to the Navigation Acts, London would control an even greater share of the most lucrative trade of the eighteenth century – sugar. Finally, the slave trade, a crime against humanity heretofore dominated by the Spanish and Portuguese, would also, from now on, enrich British coffers. (The human implications of that trade will be addressed in the next chapter.) Overall, Utrecht guaranteed that Britain would remain the greatest European trading nation during the eighteenth century, far wealthier and more powerful than any single potential enemy or ally.

Map 14

The Atlantic world after the Treaty of Utrecht, 1713.

In retrospect, the Glorious Revolution and commercial revolution had begotten the financial revolution which had enriched an important segment of the nation while guaranteeing that Britain would stop France in 1697 and defeat it in 1713. Those victories would lead to more colonies resulting in even more trade. That trade would guarantee, in turn, that when the French were ready to fight again, the British would have even more money at their disposal to plow into the War of the Austrian Succession (1742–8), the Seven Years’ War (1756–63), the American Revolutionary War (1775–83), the French Revolutionary Wars (1793–1801), and the Napoleonic Wars (1803–15). Britain would unequivocally lose only one of those conflicts, and, despite that loss, would emerge on the field of Waterloo in 1815 as the unchallenged leader of Europe and the master of a worldwide empire. All this occurred because of parliamentary sovereignty and the vision of individuals such as William III, Anne, Montagu, Marlborough, Godolphin, and Oxford in the 1690s and early 1700s. One anecdote from the memoirs of the diplomat and poet Matthew Prior (1664–1721) sums up the contrasting experiences of Britain and France. William III had sent Prior to France after the Nine Years’ War to help negotiate a Partition Treaty with Louis XIV. During the embassy, Prior spent a great deal of time at Louis’s magnificent Palace of Versailles, which was financed in part, like Louis’s wars, by crippling taxes on the French middle-class and peasantry. Prior’s French hosts, knowing full well that the British monarch could not exploit his people in the same way because of Parliament’s power, and that he had no palace of the size and magnificence of Versailles, asked Prior what he thought of their master’s house. Prior supposedly replied: “The monuments of my Master’s actions are to be seen everywhere but in his own house.”

19

Admittedly, what Prior did not say was that some of those monuments, such as the Irish Penal Code or the

Asiento,

were cruel and shameful. But for the most part, for the people of England at least, the implications of the Glorious Revolution, the commercial and financial revolutions, and the settlements at Ryswick and Utrecht would lead to national wealth and a more equitable society beyond anything experienced by Louis’s subjects.