Eclipse (17 page)

Authors: Nicholas Clee

It was âto the great astonishment of all beholders',

Town & Country

magazine reported in an archly ironic tribute to the âMonastery of Santa Charlotta', that Charlotte was able to transmute âthe basest brass into the purest gold, by a process as quick as it is unaccountable'. Charlotte provided her nuns not only with tutoring in ladylike skills, including dance and music as well as deportment, but also with fine dresses, luxurious underwear, jewellery and other adornments. She did not do so out of a spirit of lavish charity, however. She was investing in the monastery, as well as ensuring that the women, who were indebted to her for these donations, and for board and lodging too, were chained to the place unless wealthy admirers bought them out. Customers who attempted to persuade nuns to leave Santa Charlotta's without compensation for the proprietor were committing a grave breach of decorum, while those who offered presents to their favourites were in fact giving them to Charlotte.

Charlotte advertised her pampered charges by strolling with them in parks and pleasure gardens, and by gracing fashionable venues. At the opening in 1772 of the Pantheon,

79

the grand Oxford Street hall devoted to masquerades and concerts, she and several nuns were among the crowd of 1, 500 in spite of an announcement by the Master of Ceremonies that actresses and courtesans would not be admitted. The edict failed, but the MC still tried to bar the dance floor to Betsy Coxe and her then lover, Captain Scott, who observed, âIf you turn away every woman who

is not better than she should be, your company will soon be reduced to a handful!' Today, if a man took an âescort' to a party, he would probably try to disguise her occupation; his eighteenthcentury counterparts were not so squeamish.

The fashion-consciousness of Charlotte's profession is apparent in a picture entitled

A Nun of the First Class

(1773). The nun wears a tight hairdo, ascending to a point bearing a small bonnet, from which descends a row of orbs. She has a choker, a flower in her bodice, and a cheek patch

80

â these patches were originally coverings for smallpox scars, but became desirable adornments. In

A Saint James's Beauty

(1784) (which appears in this book's colour section), the nun wears a dress of some rich, heavy material; her hat sports feathers and a bow. She looks out of a window towards the palace â she is expecting a royal visitor. He may be the Prince of Wales (the future George IV), or his brother the Duke of York.

81

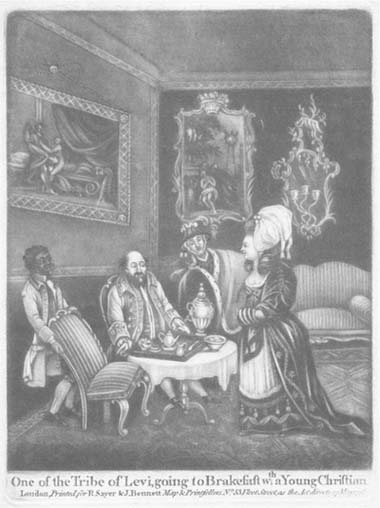

In addition to royalty and lords, Charlotte's most favoured customers were Jewish merchants and financiers. The print

One of the Tribe of Levi, going to Breakfast with a Young Christian

shows an elderly gentleman at a breakfast table in a large reception room. Above him, a painting portrays a scene of seduction. A smiling, liveried black servant boy holds a seat for the nun, who stands richly dressed for the gentleman's inspection. E. J. Burford speculated that the woman observing them from the sofa â a rather crone-like figure â is Charlotte. Jewish men, he quoted her as saying, âalways fancy that their amorous abilities never fail'; they were civil, and spoke gently.

One of the Tribe of Levi, going to Breakfast with a Young Christian

(1778).A scene from a King's Place nunnery. E. J. Burford thought that the crone-like figure in the background was âprobably' Charlotte Hayes. She was to live for another thirty-five years.

Eighteenth-century men rarely allowed their enthusiasm for sleeping with prostitutes to wilt at thoughts of the risks involved. Gonorrhoea was widespread; worse, you might get syphilis (though the distinction between the diseases was not understood), guaranteeing a terrible decline and death. Charlotte's good name depended on healthy experiences for her customers. She employed a doctor, Chidwick, to give her nuns weekly check-ups, and she provided âMrs Phillips' famed new engines' â condoms, made of dried sheep's gut and tastefully presented in silk purses, tied with ribbon. Mrs Phillips owned a shop in Covent Garden that offered âimplements of safety for gentlemen of intrigue', in three sizes. A woman of advanced marketing skills, she promoted her wares with this advertising jingle:

To guard yourself from shame or fear

Votaries of Venus, hasten here;

None in wares e'er found a flaw

Self-preservation's nature's law.

82

However, Charlotte's principles weighed lightly in the scales against commercial opportunities. In this business, you had to be flexible.

Nocturnal Revels

carried the anecdote of a nobleman who arrived at the nunnery with a plan to win a bet of 1, 000 guineas against a rival, who was cuckolding him. The bet was that the rival would be afflicted with âa certain fashionable disorder' within the next month, and the plan was this: Charlotte would provide an infected woman; the nobleman would sleep with the infected woman; the nobleman would infect his wife; the wife would infect the rival. Charlotte's first reaction to this scheme was a show of outrage. âHeavens, you astonish me!' she cried. âAnd I think you use me very ill, my Lord, considering the constant care I have

always paid to your Lordship's health and welfare. I know of no such rotten cattle as you talk of; they never come under my roof, I assure your Lordship.' In response, his lordship produced a banknote for £30. Charlotte said that she would see what she could do. The next time the nobleman met his rival in public, he demanded payment of his bet; the rival handed over the money.

James Boswell was, despite his careful use of âarmour complete', a frequent sufferer from the pox. So was the young William Hickey, who recalled treating himself with mercury (the standard medicine for the ailment) and enduring the unpleasant side-effect â exacerbated by his unwillingness to stop drinking â of âsalivation': black saliva flooded his mouth, and his tongue swelled up to prevent his ingesting anything other than fluids. Thus poisoned, he must have had a strong constitution to pull through and survive to the age of eighty.

In his entertaining account of his rackety life, Hickey noted that he was a frequent visitor to the âhouse of celebrity' kept by âthat experienced old matron Charlotte Hayes'. However, he has caused confusion by referring also to âMrs Kelly and her bevy of beauties in Arlington Street'. A passage in the

Memoirs of William Hickey

recalled an episode from 1780. Hickey was in Margate, dining with his brother and two friends, when a sumptuous landau arrived, bearing Mrs Kelly, âtwo nymphs' and a girl of twelve or thirteen. The girl, Mrs Kelly explained, was her daughter, off to a convent school in Ostend. At dinner, Hickey's brother got very drunk and made leering advances to the girl, offering such gracious observations as âthe young one's bosom had already too much swell for a nun' and âno canting hypocritical friar should have the fingering of those plump globes'. He lunged at her, but fell to the floor, insensible. Mrs Kelly rushed the girl away, and roundly abused the whole company. Hickey, undeflected by the acrimony and farce into which the evening had descended, retired to bed with one of the nymphs.

Charlotte did start to style herself Mrs O'Kelly, and the âO' was often treated as optional. But it is misguided to speculate that

she and Dennis had a daughter and sent her abroad for a convent education.

83

Hickey's Mrs Kelly is clearly someone else, who is introduced only a few pages after a mention of Charlotte Hayes and her house of celebrity; and Burford wrote about Mrs Kelly of Arlington Street (not King's Place) â her first name, according to him, was also Charlotte â as a different person. In any event, the young girl in Hickey's anecdote may not really have been Mrs Kelly's daughter, but a ward of some sort â though one who got a more sheltered education than did Charlotte's Betsy Green and Emily Warren.

84

Several of the nuns we have met in this chapter did well for themselves, escaping their cloisters to become the mistresses of wealthy men; some, such as Harriet Powell, made good marriages too. But of course they were exceptional. Most prostitutes, including those who spent their careers in the environs of St James's, endured miserable declines, which would begin before they were thirty years old. And although they were more likely to find grand lovers and husbands in Georgian London than at any other period of the capital's history, they did not enjoy complete social movement. Stigmas endured. Emily Warren became the mistress of a friend of William Hickey's, Captain Robert Pott, who on being posted to India commissioned Hickey to secure a passage for her to join him. Pott's father was dismayed. âThe unthinking boy, ' he complained to Hickey, âhas taken that infamous and notoriously abandoned woman, Emily, who has already involved him deeply as to pecuniary matters, with him to India, a step that must not only shut him out of all proper society, but prevent his being employed in any situation of respect or emolument. 'The story ended sadly.

The couple made a âgreat impression' in Madras (Chennai), and set sail for Calcutta (Kolkata); but Emily died on board, mysteriously succumbing to fever shortly after drinking two tumblers of water mixed with milk.

85

Charlotte, meanwhile, continued to prosper. In 1771, she opened a second King's Place brothel, at number 5, entrusting number 2 to a Miss Ellison. She also had an establishment in King Street, for the King's Place overspill. The German visitor Johann Wilhelm von Archenholz noted that King's Place was clogged with carriages in the evenings, and observed of the nuns, âYou may see them superbly clothed at public places; and even those of the most expensive kind. Each of these convents has a carriage and servants in livery; for the ladies never deign to walk anywhere, but in the park.'

Charlotte was in her pomp. Edward Thompson, who had followed her progress, wrote in the 1770 edition of his poem

The Meretriciad

:

So great a saint is heavenly Charlotte grown

She's the first lady abbess of the town;

In a snug entry leading out Pell Mell

(which by the urine a bad nose can smell)

Between th'hotel

86

and Tom Almack's house

The nunnery stands for each religious use;

There, there, repair, you'll find some wretched wight

Upon his knees both morning noon and night!

However, no businesswoman could afford to be complacent. Rivals were always threatening to challenge one's status as London's most fashionable hostess, and the entertainments at Mrs

Cornelys's soirées or at the Pantheon might lure away customers. One had to innovate.

Accounts of James Cook's voyages in the Pacific had found an enthralled audience in England. When in 1774 Commander Tobias Furneaux returned from Cook's second voyage, he brought with him Omai, a young Tahitian, who made a great impression on society. An ode entitled

Omiah

was addressed to Charlotte Hayes, whom for some reason the poet enjoined to coax Lord Sandwich (âJemmy Twitcher') to secure Omai's homeward passage.

Sweet Emily, with auburn tresses,

Will coax him by her soft caresses,

And Charlotte win the day;

Old Jemmy's goatish eyes will twinkle;

Lust play bo-peep from every wrinkle;

But first bribe madam Ray.

87

What fired Charlotte's imagination were the sexual rites of the Pacific islanders. One ceremony involved the deflowering of a young girl in front of an audience of village notables, with a venerable woman called Oberea presiding. Charlotte decided to recreate the spectacle in King's Place, but to introduce more variety to it: there would be not one virgin, but a dozen (as her definition of virginity was loose, the casting did not present a challenge). She hired a dozen lusty young men, with whom the âunsullied and untainted' nymphs would perform under the tutelage of Queen Oberea, âin which character Mrs Hayes will appear on this occasion'. Charlotte's invitation advised that the rites would begin âprecisely at seven'. Twenty-three men accepted, mostly including âthe first nobility', along with a few baronets, and five commoners.

The spectacle entertained these dignitaries for two hours, and âmet with the highest applause from all present'. When a collection came round for âthe votaries of Venus', there was a generous response. Their blood up, the distinguished gentlemen now got their own opportunity to perform with the young women. The evening ended on a festive note, with champagne and musical entertainment in the form of catches and glees. In the account in

Nocturnal Revels

, an exhausted but exultant Charlotte, her last guest having departed at four in the morning, âthrew herself into the arms of the Count, to practise, in part at least, what she was so great a mistress of in theory'.

It was the greatest triumph of Charlotte's career, her equivalent of the moment in April 1770 when Eclipse galloped clear of Bucephalus. She was established, and rich, recognized as the nonpareil of her profession. She was the companion of the owner of the greatest racehorse of the day. Charlotte and Dennis were at the summits of two of the most important leisure industries in Britain.