Ed McBain_Matthew Hope 12 (4 page)

Read Ed McBain_Matthew Hope 12 Online

Authors: Gladly the Cross-Eyed Bear

Tags: #Hope; Matthew (Fictitious Character) - Fiction, #Detective and Mystery Stories, #Lawyers, #Mystery & Detective, #Hope; Matthew (Fictitious Character), #Lawyers - Florida - Fiction, #Florida, #Legal, #Fiction, #Legal Stories, #General, #Florida - Fiction

“I left them in January. I’d been working there for three years by then.”

“This past January?”

“Yes.”

“Worked for them for three years.”

“Yes.”

“Do you remember which toys you designed for them during those three years?”

“I remember all of them.”

“Wasn’t the idea for Gladly suggested to you…?”

“No, it was not.”

“Your Honor, may I finish my question?”

“Yes, go ahead. Please listen to the complete question before answering, Miss Commins.”

“I thought he

was

finished, “Your Honor.”

“Let’s just get on with it,” Santos said impatiently.

“Isn’t it true that the

idea

for Gladly was suggested to you by Mr. Toland…?”

“No, that isn’t true.”

“Miss Commins, let him

finish,

please.”

“Suggested to you by Mr. Toland at a meeting one afternoon during the month of September last year?”

“No.”

“While you were still in the employ of…?”

“No.”

“…Toyland, Toyland, isn’t that true, Miss Commins?”

“No, it is not true.”

“Isn’t it true that this

original

idea of yours was, in fact, Mr. Toland’s?”

“No.”

“Didn’t Mr. Toland ask you to work up some sketches on the idea?”

“No.”

“Aren’t the sketches you showed to the court identical to the sketches you made and delivered to Mr. Toland several weeks

after that September meeting?”

“No. I made those sketches this past April. In my studio on North Apple Street.”

“Oh yes, I’m sure you did.”

“Objection,” I said.

“Sustained. We can do without the editorials, Mr. Brackett.”

“No further questions,” Brackett said.

Warren debated opening the door again, ramming a toothpick into the keyway, snapping it off close to the lock. Anyone trying

to unlock the door from the outside would try to shove a key in, meet resistance, make a hell of a clicking racket pushing

against the broken-off wood. Great little burglar alarm for anybody inside who shouldn’t be in there. Trouble was,

she

knew the toothpick trick as well as he did, she’d know immediately there was somebody in her digs. He’d be lucky she didn’t

pull a piece, blow off the lock, and then shoot at anything that moved, blowing off his

head

in the bargain.

He locked the door.

Looked around.

The place was dim. White metal blinds drawn against the sun at the far end of the room. Sofa against what was apparently a

window wall, sunlight seeping around the edges of the blinds. Sofa upholstered in a white fabric with great big red what looked

like hibiscus blossoms printed on it. His eyes were getting accustomed to the gloom. The place looked a mess. Clothes strewn

all over the floor, empty soda pop bottles and cans, cigarette butts brimming in ashtrays—he hadn’t known she’d started smoking

again, a bad sign. He wondered if the place always looked like a shithouse, or was it just now? On the street outside, he

heard a passing automobile. And another. He waited in the semidark stillness of the one room. Just that single window in the

entire place, at the far end, the only source of light, and it covered with a blind. Figured the sofa had to open into a bed,

else where was she sleeping?

Door frame, no door on it, led to what he could see was a kitchen. Fridge, stove, countertop, no window, just a little cubicle

the size of a phone booth laid on end, well, he was exaggerating. Still, he wouldn’t like to try holding a dinner party in

there. He stepped into the room, saw a little round wooden table on the wall to his right, two chairs tucked under it. Kitchen

was a bit bigger than he’d thought at first, but he still wouldn’t want to wine and dine the governor here.

Pile of dirty dishes in the sink, another bad sign.

Food already crusted on them, meant they’d been there a while, an even worse sign.

He opened a door under the sink, found a lidded trash can, lifted the lid, peered into it. Three empty quart-sized ice cream

containers, no other garbage. Things looking worse by the minute. He replaced the lid, closed the door, went to the fridge

and opened it. Wilting head of lettuce, bar of margarine going lardy around the edges, container of milk smelling sour, half

an orange shriveling, three unopened cans of Coca-Cola. He checked the ice cube trays. Hadn’t been refilled in a while, the

cubes were shrinking away from the sides. He nearly jumped a mile in the air when he spotted the roach sitting like a spy

on the countertop alongside the fridge.

They called them palmetto bugs down here. Damn things could fly, he’d swear to God. Come right up into your face, you weren’t

careful. Two, three inches long some of them, disgusting. There were roaches back in St. Louis, when he lived there, but nothing

like what they had down here, man. He closed the refrigerator door. Bug didn’t move a muscle. Just sat there on the countertop

watching him.

Another car passed by outside.

Real busy street here, oh yes, cars going by at least every hour or so, a virtual metropolitan thoroughfare. He just hoped

one of them wouldn’t be

her

car, pulling into the parking lot, home from market, surprise!

He figured that’s where she’d be, ten-thirty in the morning, probably down in Newtown, doing her marketing. He hoped to hell

he was wrong. The roach—palmetto bug, my ass!—was still on the countertop, motionless, watching Warren as he went back into

the main room of the unit, the living room/bedroom/dining room, he guessed you would call it. Red hibiscus sofa against the

far wall, he walked to it, and leaned over it and opened the blinds, letting in sunlight.

I had only one other witness, an optometrist named Dr. Oscar Nettleton, who defined himself as a professional engaged in the

practice of examining the eye for defects and faults of refraction and prescribing corrective lenses or exercises but not

drugs or surgery. He modestly asserted that he was Chairman of, and Distinguished Professor in, Calusa University’s Department

of Vision Sciences. I elicited from him the information that Lainie Commins had seemed elated…

“Objection, Your Honor.”

“Overruled.”

…and glowing with pride…

“Objection.”

“Overruled.”

…and confident and very up…

“Objection.”

“Sustained. One or two commonsense impressions are quite enough for me, Mr. Hope.”

…when she’d come to him this past April with her original drawings for Gladly and her requirements for the eyeglasses the

bear would wear.

“She kept calling them the specs for the specs,” Nettleton said, and smiled.

He testified that his design for the eyeglasses was original with him, that he’d received a flat fee of three thousand dollars

for the drawings, and had signed a document releasing all claim, title and interest to them and to the use or uses to which

they might be put.

Brackett approached the witness stand.

“Tell me, Dr. Nettleton, you’re not an ophthalmologist, are you?”

“No, I’m not.”

“Then you’re not a physician, are you?”

“No, I’m not.”

“You just make eyeglasses, isn’t that so?”

“No, an

optician

makes eyeglasses. I prescribe correctional lenses. I’m a doctor of optometrics, and also a Ph.D.”

“Thank you for explaining the vast differences, Doctor,” Brackett said, his tone implying that he saw no real differences

at all between an optician and an optometrist. “But, tell me, when you say the design for these eyeglasses is original with

you, what exactly do you mean?”

“I mean Miss Commins came to me with a problem, and I solved that problem without relying upon any other design that may have

preceded it.”

“Oh?

Were

there previous designs that had solved this problem?”

“I have no idea. I didn’t look for any. I addressed the problem and solved it. The specifications I gave her were entirely

original with me.”

“Would you consider them original if you knew lenses identical to yours had been designed

prior

to yours?”

“My design does not make use of lenses.”

“Oh? Then what are eyeglasses if not corrective lenses?”

“The lenses in these glasses are piano lenses. That is, without power. They are merely clear plastic. If you put your hand

behind them, you would see it without distortion. They are not corrective lenses.”

“Then how do they correct the bear’s vision?”

“They don’t, actually. They merely

seem

to. What I’ve done is create an illusion. The teddy bear has bilaterally crossed eyes. That is to say, the brown iris and

white pupil are displaced nasalward with respect to the surrounding white scleral-conjunctival tissue of the eye. As in the

drawing Ms. Commins first brought to me. What I did…”

“What you did was design a pair of eyeglasses you say are original with you.”

“They are

not

eyeglasses, but they

are

original with me.”

“When you say they’re original, are you also saying you didn’t copy them from anyone else’s eyeglasses?”

“That’s what I’m saying. And they’re

not

eyeglasses.”

“Your Honor,” Brackett said, “if the witness keeps insisting that what are patently eyeglasses…”

“Perhaps he’d care to explain why he’s making such a distinction,” Santos said.

“Perhaps he’s making such a distinction because he knows full well that his design is copied from a pair of eye—”

“Objection, Your…”

“I’ll ignore that, Mr. Brackett. I, for one, certainly

would

like to know why Dr. Nettleton doesn’t consider these eyeglasses. Dr. Nettleton? Could you please explain?”

“If I may make use of my drawings, Your Honor…”

“Already admitted in evidence, Your Honor,” I said.

“Any objections, Mr. Brackett?”

“If the Court has the time…”

“I do have the time, Mr. Brackett.”

“Then I have no objections.”

I carried Nettleton’s drawings to where he was sitting in the witness chair. He riffled through the stapled pages and then

folded back several pages to show his first drawing.

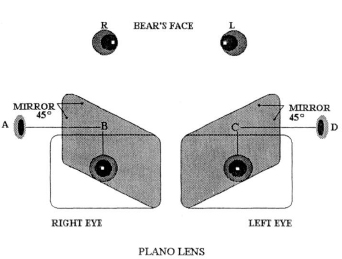

“These are the plastic crossed eyes that are attached to the teddy bear’s face. As you can see, the iris and pupil are displaced

nasalward.”

“And this is a drawing of the plastic

straight

eyes as they’re reflected within the spectacles I designed.”

“May I see it, please?”

Nettleton handed the drawing to him.

“By reflected…”

“With mirrors, Your Honor.”

“Mirrors?”

“Yes, Your Honor. If I may show you my other drawings.”

“Please.”

Nettleton turned some more pages, folded them back, and displayed another drawing to Santos.

“This is the teddy-bear optical schematic,” he said. “It illustrates the manner in which I expressed the optical principles

of my system for producing apparently straight eyes. A and D are button eyes that will be seen by reflection from the right

and left mirrors. Their images only

appear

to be at R and L respectively.”

“For the right eye, the distance from A to B equals the distance from B to R at the plane of the bear’s face. Similarly, for

the left eye, the distance from C to D equals the distance from C to L. The lenses, as I mentioned earlier, are plano lenses.”